An Early Resolution: Frederic Whiting (1920–30)

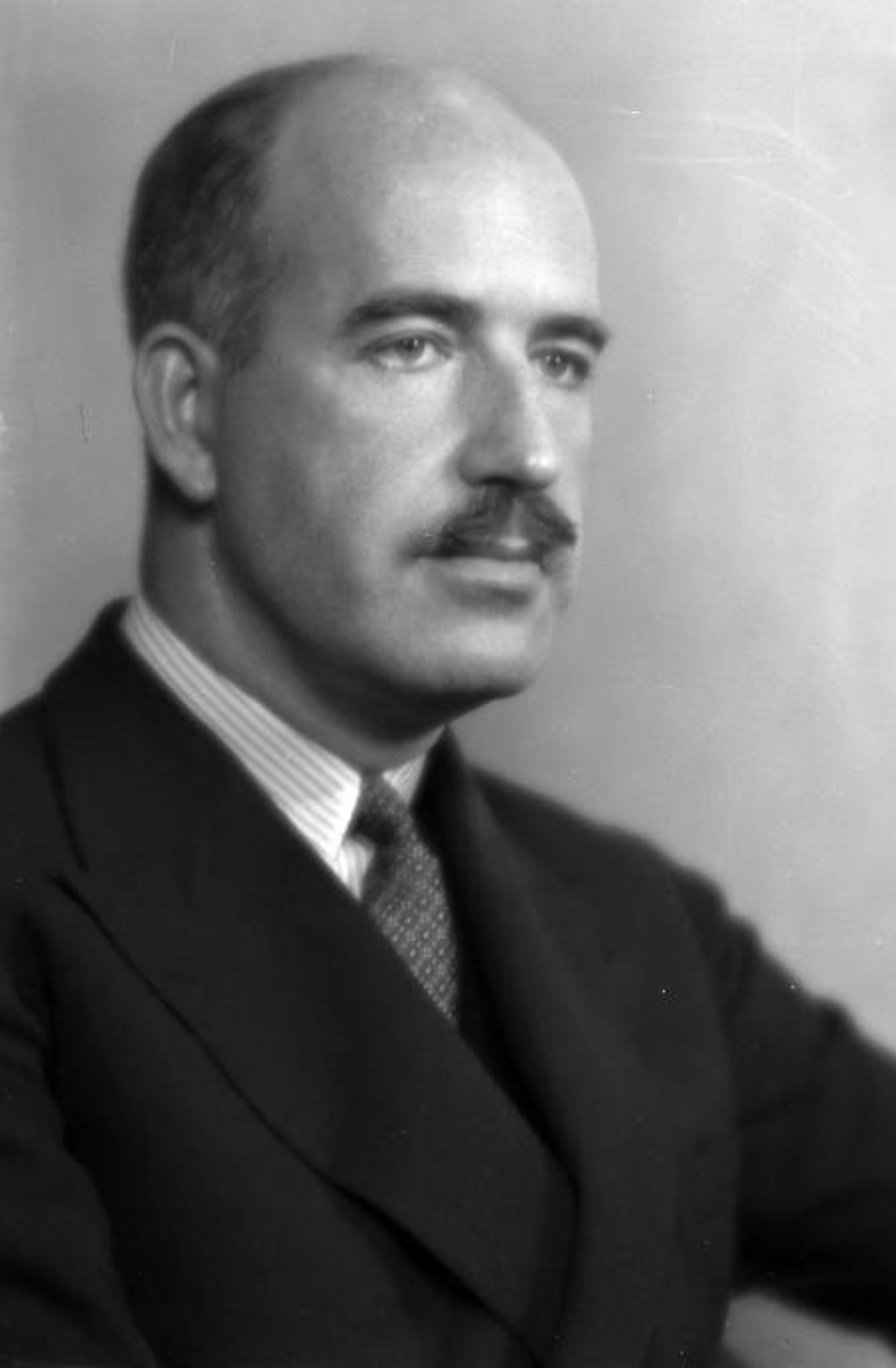

In 1920, four years after the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) opened, its Board of Trustees resolved that it would display “the art of primitive Americans, such as Peruvian, Mexican, and North American Indian . . . which would be the first attempt of an American museum to show in a constructive way [that is, not as archaeological artifact] the art of those who lived here before the white man came.”1 The impetus for the resolution, unrealized until 1926, probably stems in part from the background of its author, Frederic A. Whiting (1873–1959), the museum’s first director (fig. 1). Prior to his arrival in Cleveland, he had been deeply involved in the Arts and Crafts movement in New England, serving as secretary of Boston’s nationally influential Society of Arts and Crafts for a dozen years, among other things.2 The Arts and Crafts movement embraced handcraftsmanship and precapitalist forms of society, such as those of the aboriginal Americas, as antidotes to the impacts of industrialization.3 In line with these ideas, Whiting and at least some trustees conceived of the museum’s collection above all else as an educational resource for the immigrants who worked in the industries that were a source of Cleveland’s early-twentieth-century wealth.4

It is a measure of Whiting’s ambition in the field that in the 1920s he considered acquiring two ancient Andean collections, one valued at a respectable $29,000 (today, over $500,000).5 That acquisition had been recommended by Philip Ainsworth Means (1892–1944), an Andean specialist and one of the many archaeologists with whom the CMA would eventually consult about authenticity and related matters. Neither purchase came to fruition, however, and during the first few decades, the collection consisted almost entirely of modest gifts from the city’s prosperous citizens, among them the first of several women who played strong roles in the formation of the museum’s Indigenous American holdings.

Thus, Whiting’s greatest contribution to the field was not building the collection but rather advocating for Indigenous arts as worthy of an art museum’s attention. In 1929, in one of his last acts before resigning, he named the art historian and artist Charles F. Ramus (1902–1979) “In Charge of Primitive Art,” a designation that bundled together and singled out Indigenous American, African, and Oceanic arts while falling short of a curatorial appointment. In doing so, he was likely encouraged by Mary Gardiner Ford (d. 1959), a museum supporter who in the same year created a fund dedicated to the acquisition of primitive art, especially from the ancient Americas, in memory of her late husband.6

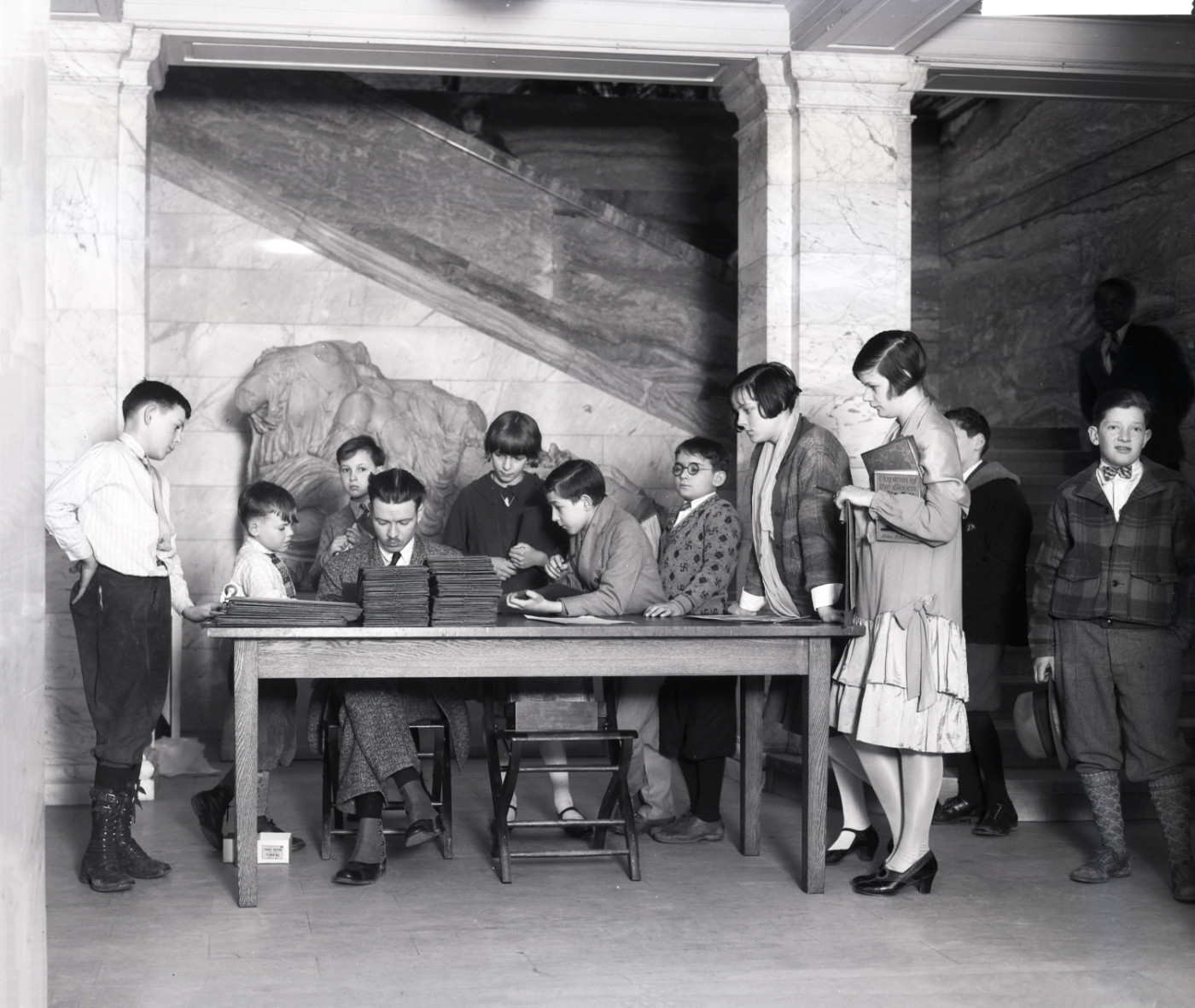

During Ramus’s brief employment (he resigned in early 1935), he made the museum’s first nontextile ancient American purchases—three bowls winnowed from a large group of Andean (Nazca) ceramics offered by the Argentine dealer Mauro Enrique Pando y Pomar.7 He also organized several temporary installations of primitive art for both the general public and children, the latter because, like some other early curators, he divided his time with the Department of Educational Works (fig. 2). His efforts in this vein included what may have been the museum’s first ancient American exhibition based on loans, Comparative Pottery and Peruvian Textiles, in 1931.8 It is worth noting here that in the early years, educators played a strong role in promoting primitive arts in Cleveland, especially after the hire of Thomas Munro (1897–1974), an internationally noted aesthetic philosopher, as Curator of Education in 1931.9 From the start, the department had its own funds to purchase objects for use in public outreach programs, and the education art collection, which includes Indigenous American arts, eventually grew to be substantial.

Beginnings of the Collection: William Milliken, Emery May Norweb, and John Wise (1930–58)

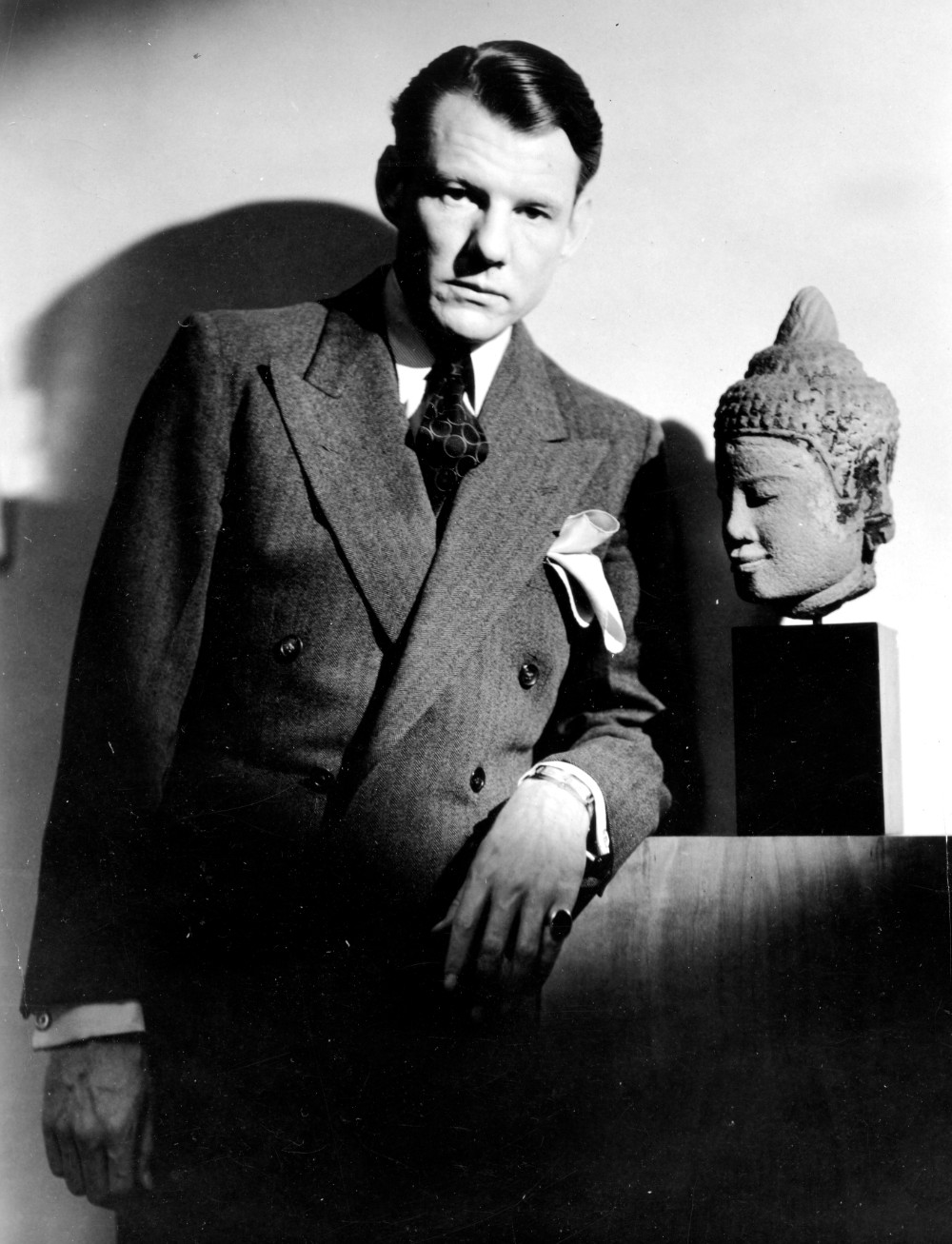

In 1930, after Whiting’s departure, the trustees promoted William M. Milliken (1889–1978), who had been hired as the museum’s first decorative arts curator in 1919, to become its second director (fig. 3). Like Whiting, Milliken had no formal arts training, though he took art history courses during his studies at Princeton University. It was through his experience in museums—first on the curatorial staff of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he worked with J. Pierpont Morgan’s medieval collection, and then in Cleveland—that he developed interests in the medieval and the French Gothic and Baroque periods, distinguishing himself in acquisitions through his taste for small, finely wrought objects made of precious materials.10 During his directorship, he continued in his curatorial role, apparently assuming responsibility for primitive arts after Ramus departed. Though the Great Depression withered the museum’s budget throughout the 1930s, Milliken went on in the 1940s and 1950s to amass the core of the CMA’s ancient American collection. Crucially, he did not do so alone but rather with the collaboration of an important trustee, Emery May Holden Norweb (1895–1984), and the help of an ambitious art dealer, John Wise (1901–1981).11

Norweb was a member of Cleveland’s economic and social aristocracy whose family, the Holdens, had been involved in the museum as trustees from its inception (fig. 4).12 Following suit, she joined the Advisory Council in 1940 and soon became a member of the board, serving as its sixth president during the 1960s—the first of only two female board leaders so far. She was undoubtedly aided in her accomplishments on the board not only by her family ties but also by her long experience as the wife of a diplomat, R. Henry Norweb, who served in posts primarily in Latin America, including ambassadorships in Peru and Cuba and lesser positions in Mexico, Bolivia, and elsewhere.13 It was in Chile, in 1930, that she recalled having started to collect in the field, saying that her eyes “were opened to pre-Columbian art, and people who were experts in the field began to bring me things. It was a gorgeous opportunity because no one was buying it then.”14 The unnamed experts may have been some of the archaeologists who, like Means, routinely conferred with collectors, curators, and dealers at the time.15 Ten years later, in 1940, she began to make a series of gifts that transformed the CMA’s collection and helped open the ancient Americas as a collecting area.

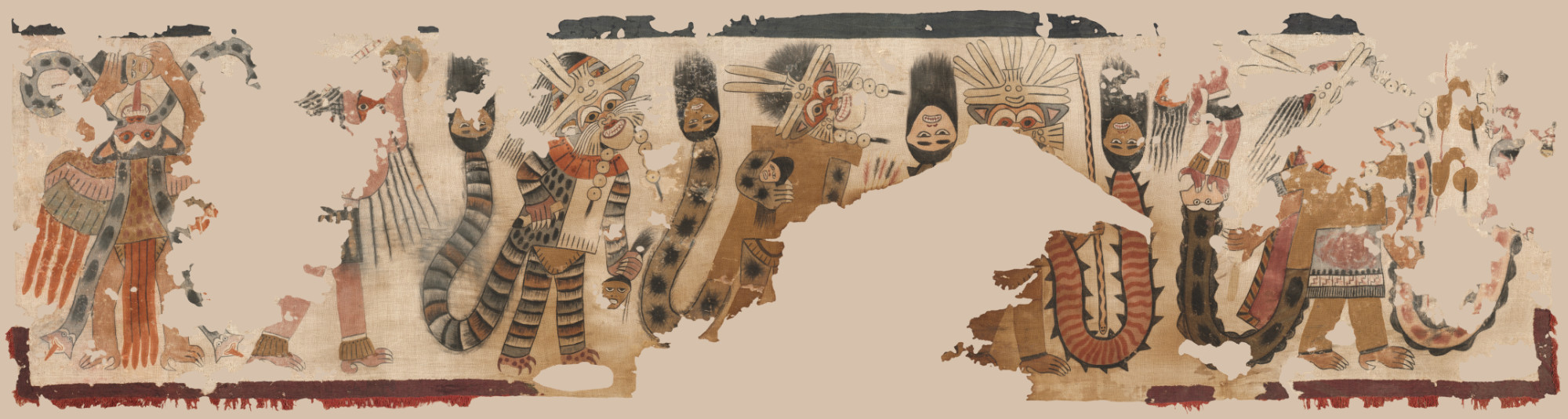

The Norweb Collection of ancient American art comprises about seventy objects, most from the Andes, a focus that continued early interest in the region.16 Among her gifts are a group of South Coast textiles that remain anchors of the collection, including the magnificent lower half of an early Nasca mantle regarded as the greatest painted cloth to have survived from the region (fig. 5). These textiles seem to have helped to convince the young director that ancient American arts, which he had disparaged as archaeological, possessed artistic merit.17 She also donated or contributed funds to purchase key objects from Mesoamerica and the Isthmian region (fig. 6). It may be that she acquired some of the works in her collection while living in Latin America, though there seem to be no records identifying them; she also purchased material in the United States.18

One of her US sources was John Wise, the Virginia-born, Harvard-educated, New York–based stockbroker, who, having been financially ruined in the crash of 1929, began selling family heirlooms (fig. 7). He went on to become a major ancient American arts dealer—the king of midcentury East Coast dealers, in the words of Michael Coe, a contemporary and Yale University anthropologist and curator.19 It seems that neither Milliken nor Norweb were acquainted with Wise when, in 1939, he visited Cleveland and offered the museum an Isthmian gold pendant that Milliken found “extraordinary” (fig. 8). Lacking funds, Milliken contacted Norweb, who agreed to purchase it for the museum.20 Years later, Wise recalled this as his first sale of an ancient American object to a museum dedicated to art and a turning point in the appreciation of ancient American art.21 The encounter seems to have begun a long friendship between Milliken and Wise that Coe singles out for mention and is discernible in the warm, joking correspondence preserved in Milliken’s papers (fig. 9).22 During the period of Milliken’s stewardship, Wise was by far the most common source of ancient American objects that entered the collection, whether by direct purchases or as gifts from donors or Wise himself.

In addition to Norweb, Helen Humphreys was the most notable member of the ancient American collecting community centered on Milliken and the museum. A Spanish teacher in Cleveland’s public school system, she wished to create a memorial to her late parents and originally considered focusing her attention on objects of peninsular Spanish origin to do so. But she turned instead to the ancient arts of the Spanish colonies, one suspects with Milliken’s encouragement, and over two decades donated forty-six works, about half of them Isthmian gold ornaments but also others (fig. 10).23 Milliken thought that her donations came from her teacher’s salary, but she may have had family money: In one five-year period in the 1940s, her cash contributions for acquisitions totaled at least $43,500 (well over $700,000 today). As this implies, she regularly gave funds to the museum and allowed Milliken to negotiate and finalize purchases on her behalf, but she also bought directly—in both cases, usually from Wise, when the source is recorded.24 Her process for selecting objects is not known, but Milliken’s guiding hand may be betrayed by her collection’s emphasis on small-scale objects made of precious materials.

Aside from Norweb, several other trustees, two of them also women, supported ancient American acquisitions during Milliken’s years, though more episodically: Jane Taft Ingalls (1874–1962), niece of William Howard Taft; Roberta Holden Bole (1876–1950), Norweb’s aunt; and Leonard C. Hanna Jr. (1889–1957), heir to a Great Lakes industrial fortune and by far the museum’s most important donor. His collecting focused on European art, but he was interested in the ancient Americas and is said to have spent many hours in Wise’s gallery.25

Apart from acquisitions, Wise was also very involved with Art of the Americas, an important exhibition, discussed below, that Milliken organized in the mid-1940s. Wise’s contributions included lending objects and donating funds for an exhibition publication. Perhaps most notable from today’s perspective, however, is the fact that he also stepped in when, three months before the show opened, one of Milliken’s brothers died suddenly, and Milliken, describing himself as stunned and desolated, went to Wyoming for two months of rest.26 In letters to lenders, he deputized Wise as his representative in loan affairs—not Helen Foote, a junior decorative arts curator who assisted Milliken on the project—and Wise seems to have visited museums and negotiated loans on Milliken’s behalf.

There can be no doubt that Wise was a businessman whose activities were calculated to advance his commercial interests. But Coe, who knew him well and advises caution in judging activities that occurred in a climate radically different from today’s, describes Wise as a benefactor and good friend when it came to the CMA and Milliken.27 Wise’s motivations for being so may be revealed in a conversation he had in 1945 with Natacha Rambova, an American Hollywood costume and set designer interested in tracing designs that appear in art across cultures. She related the conversation in a letter to Milliken, writing that Wise “feels about that Museum as you do. In a way he feels it is also his baby and would do anything he can to help your pre-Columbian wing. Apparently, he has been fighting for this early American art for years and seems to want to leave something worthwhile, to feel he has been able to accomplish something of real value.”28 Milliken left no explanation of his own reasons for pursuing the ancient Americas so avidly except to say that it was a matter of opportunity following a lucky coincidence—the meeting that involved the Isthmian pendant (see figure 8).29 His report of his first encounter with Norweb’s Andean textiles, during which he described himself as “breathless” and “transfixed,” suggests that, at least at the beginning, the area may have been one of the intense enthusiasms for which he was known, this one reinforced by Norweb’s and Wise’s mutual interest.30

In CMA publications, Milliken’s effort with the ancient American collection is usually said to be among his greatest achievements—and one he shared with Norweb.31 They were abetted by the other donors discussed here and probably also by wartime disruption of European and Asian markets, competitive pricing of ancient American arts compared to those of many other places and periods, and interest in Pan-Americanism that was widespread at the time.32 When Milliken retired in 1958, he left the museum’s Andean holdings about twice as strong numerically as those from either of the other two regions, though the collection is also said to have been noted for its Isthmian gold, thanks in part to Humphreys.33 Besides textiles, holdings were also strongly focused on the small, precious, three-dimensional objects that were Milliken’s predilection.

Art of the Americas Exhibition (November 9, 1945–January 6, 1946)

As noted above, in 1945, with Helen Foote’s and Wise’s help, Milliken organized Art of the Americas, which, strikingly, was one of the few largish exhibitions the museum staged in the postwar period.34 His intention for the show seems to have been, in part, to celebrate new acquisitions, which, in his opinion, had boosted CMA’s ancient American collection into the first rank. Above all, however, was his nationally noteworthy ambition to prove that the “art of the Western Hemisphere can stand on its own feet.”35 It follows that the exhibition made no pretense of being comprehensive, instead embracing quality and beauty as the sole criteria for object selection—borrowing a phrase from Milliken, an ARTnews review valorized the “strange beauty” of ancient American art.36 The result was an unsystematic sampling of all three ancient culture areas that brought together works from twenty-seven institutions, private collectors, and dealers around a core of CMA objects. The show, which is documented in a series of black-and-white photos, was laid out in geographic clusters in two galleries, with Andean textiles ranged along the walls to encircle large cases containing objects of clay, metal, and other media.

Certain design features seem to have advanced Milliken’s goal for the show. For instance, cases were divided internally by panels in an arrangement that, according to ARTnews, showed each object in its “most felicitous aspect”—in other words, as a work of art.37 Also, other three-dimensional objects were placed individually on pedestals against the walls, perhaps to emphasize their sculptural qualities and silhouettes, in addition to calling them to visitors’ attention. Finally, though the old installation photos are grainy and often difficult to decipher, texts and other interpretive materials seem to have been minimal, as though to reduce distractions that would compete with the artworks.

In the Bulletin and many letters to lenders and donors, Milliken exulted that the show was “one of the most successful and popular” in the museum’s history and that it drew enthusiastic, appreciative visitors from both the East and West Coasts.38 One was M. D. C. Crawford, a self-taught expert and champion of ancient Andean textiles, consultant to major museums, and trustee of the Textile Museum in Washington, DC, among other things. His reaction appears to have been representative: “I think it is, barring none, the finest exhibition of its kind for choice and presentation I have ever seen.”39 Local response was no less rapt; for instance, after seeing the show, N. R. Howard, editor of the Cleveland News, wrote to a board member, “That durn show moved me more than anything I have seen for a long time.”40 Perhaps due to this reception, after the show closed the museum invested an amount of money that today is surprising—$5,300 (now, over $70,000)—in a small, fifty-eight-page booklet to create a pictorial record of the effort (fig. 11).41

The Monuments Men: Sherman Lee and Henry Hawley (1958–89)

When Milliken departed, Sherman E. Lee (1918–2008) soon succeeded him to become the institution’s third director. Familiar with the museum through his service as Curator of Oriental Art since 1952, he lost no time in expressing his “strong feeling” that the ancient American collection required “larger sculptures and . . . other items . . . not already represented in the collection.” He made this stipulation in a letter to Wise that accompanied the return of three dozen small objects that apparently had been at the museum for Milliken’s consideration.42 Also, an analysis revealed that the decorative arts had received the lion’s share of acquisition funds since the museum’s founding, while Western paintings languished. Thus, Lee and the trustees, soon to be led by Norweb, agreed in the future to devote no more than 15 percent of the budget to the decorative arts, including ancient American art.43 Another decision, unspoken in memos but clear in acquisition records, was to diversify the sources from whom material was purchased. Supplanted by a variety of other sellers, Wise placed only a few more works with the museum before he died in 1981.44

Despite constraints, a number of the collection’s most iconic works were purchased over the next decade under the guidance of Henry H. Hawley (d. 2019), another European decorative arts specialist who assumed responsibility for the Indigenous Americas when he was hired in 1960 (fig. 12). He arrived at the CMA fresh from the University of Delaware Winterthur Program, where he wrote a master’s thesis about Euro-American decorative arts. No doubt responding to Lee’s imperatives about collection development, with which he may have agreed, in the 1960s, Hawley bought four of the museum’s largest ancient American objects (excluding textiles), most obviously the nine-foot-tall front face of a Maya stela, together with several smaller works (figs. 13 and 14). All but a few are from Mesoamerica, perhaps due in part to an interest in correcting the collection’s Andean tilt. Also, the Mesoamerican art market more frequently offered the large-scale works that were of interest at the time, a decade during which the illicit removal of monumental and architectural art from Mexico and Guatemala reached a crescendo.45 Aesthetically, Hawley leaned toward the region’s realistic styles, especially Maya.

During the 1970s, Hawley remained in charge of the ancient American collection, purchasing a few more of its best-known works. Except for a handful of gifts, however, acquisitions stopped after 1973 due to increasing sensitivities about collecting that culminated in the 1970 UNESCO convention on cultural property and its guidelines for diminishing the illegal traffic in antiquities.46 By the early 1980s, Hawley seems to have transferred care of the ancient Americas to Virginia Crawford, an assistant decorative arts curator. During his stewardship, he presided over a dramatic decline in acquisitions caused by the shifting milieu and a thinning of the ranks of the group of donors who had clustered around Milliken. But Hawley’s contributions, characterized by their great beauty and refinement, had a considerable impact on the collection.

Over the next sixteen years, the museum purchased only one ancient American object, an Aztec gold warrior figurine (1984.37), during the directorship of Evan H. Turner, Lee’s successor. A modernist and self-described “paintings man” whose interests lay outside the Americas, Turner nevertheless seems to have masterminded the CMA’s 1986 participation in an important ancient American exhibition organized by the Kimbell Art Museum: The Blood of Kings: A New Interpretation of Maya Art, one of the CMA’s most successful exhibitions of the decade and one that gave rise to a local community of Maya enthusiasts.47 Its popularity may have encouraged Turner to undertake the museum’s first attempt to recruit a curator trained in the ancient American specialty when Crawford, who shepherded the exhibition through its Cleveland appearance, resigned her position.48

The Creation of a Department: Margaret Young-Sánchez (1989–99)

Margaret Young-Sánchez arrived in 1989, as she was finishing a doctoral dissertation about Andean textiles in Columbia University’s art history program. Apparently coincidentally, the following year saw the arrival of the largest gift in the collection’s history—149 objects from the estate of James and Florence Gruener (1903–1990; 1908–1982), long-time Clevelanders and museum supporters who had retired to California. During the 1930s, the Grueners began to travel widely in Mexico, where they became fascinated by folk and ancient art traditions alike. Her attraction appears to have been aesthetic while his interest was in the perceived similarities among the religions of Native America and other parts of the world, and he eventually self-published a book on the topic.49 Most of their collection is Mesoamerican, representing a relatively complete sampling of the region’s major styles (fig. 15).

Once Young-Sánchez had processed and organized an exhibition of the bequest, she embarked on a very active acquisition campaign during the brief directorship of medievalist Robert Bergman (1993–99).50 Concerned more with quality than with filling gaps or balancing regional representation, she collected with a relatively even hand across the three ancient culture areas, buying to both strengths, especially the Maya collection, and weaknesses, including Isthmian region ceramics, as objects of high caliber became available (figs. 16 and 17).51 A notable exception to her collecting practice was Andean textile holdings, which had been static since Norweb’s foundational gifts of the 1940s and remained so in the 1990s due to the textile curator’s interest in other traditions.52 A few patterns established during Hawley’s tenure continued. First, acquisitions came from a range of dealers. Also, apart from the Gruener bequest, few other gifts arrived, the most significant of which was from Clara Taplin Rankin, a veteran of the Milliken era, long-time trustee, and supporter of the ancient Americas. Frances (Franny) Prindle Taft (1921–2017) also contributed to building the collection via her decades-long trusteeship rather than donations.

Records of Young-Sánchez’s activity during the decade—not only acquisitions but also publications, reinstallation, and exhibitions (both realized and proposed)—create the impression of a determined effort to amplify the voice of the Americas within the museum after a long period of relative quiescence and to improve national awareness of the collection, which she described as “one of the finest in the US.”53 She had been hired as an assistant curator of decorative arts. Before resigning in 1999, she had succeeded in establishing a department independent of the decorative arts that included not only the arts of the Americas but also the arts of Africa and Oceania, which had been part of her portfolio.

Back to the Future: Susan Bergh and Renewed Commitment (2000–23)

The next director—the deeply sympathetic Katharine Lee Reid (1941–2022), daughter of Sherman Lee—created separate curatorships for Indigenous American and African arts under the sensible rationale that the areas have little to do with each other.54 In 2000, I assumed the Americas position, also shortly after completing a doctoral thesis about Andean textiles at Columbia University, and served in it for over two decades. I will leave to a future curator the task of summarizing my collection development activities except to say that, as in the museum’s early days, efforts focused most strongly on Andean arts, including textiles, now in an attempt to put them on more equal footing with the Mesoamerican holdings that had come to dominate the collection (fig. 18). I did so in the belief that, when possible, fine objects with pre-1970 provenance should be safeguarded and made available for study in museums while collecting standards, relationships with source countries, and guidelines for repatriation continue to evolve. A major loan exhibition that I organized, Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes (2010), also concerned the central Andes.

During my tenure, another full-circle moment occurred in 2022, when the museum adopted an “Indigenous Peoples and Land Acknowledgment” that, without explicitly intending to do so, renewed the museum’s 1920 resolution to foster appreciation of Indigenous American arts and the alternative ways of thought they embody.55 Importantly, the acknowledgment also updated the early resolution by orienting attention as much toward people as toward art, especially building collaborative relationships with Indigenous artists and communities. In this spirit, I wrote the acknowledgment, my last official act, following the directions of a committee of local Native North American advisors, some of whom belong to historic Ohio tribes, such as the Haudenosaunee, who were driven from the state after the 1830 passage of the Indian Removal Act. The families of others, including members of Pueblo and Lakota nations, had moved to Cleveland under the auspices of the federal urban relocation programs in the 1950s through the 1970s. Since the acknowledgment was adopted, and in contrast to a decades-long pattern of neglecting Indigenous North American arts, the CMA has added several contemporary works to its collection—the first was Survival, a suite of color lithographs by the Salish, Shoshone, and Métis artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.56 It remains to be seen whether this refreshed and reoriented commitment will transform into an acquisition program that bypasses the world of the archaeological past to focus on the realm of the living and the present throughout the Indigenous Americas.

Final Thoughts

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s ancient American collection is the result of early aspirations concerning the Indigenous Americas that did not begin to be realized until the mid-twentieth century. Efforts often reflected preoccupations not unique to Cleveland.57 Most centrally, from the outset, CMA directors and curators joined a broader, well-known struggle to improve these arts’ respectability and appeal to Euro-American audiences, including academics whose interest would promote further study. They did so through attempts to validate the material as art rather than archaeological artifact. This endeavor was among the many factors that led to a livelier interest and market in ancient American arts, which, in turn, fed midcentury collecting peaks in Cleveland and elsewhere. In the 1970s, ancient American collecting declined at the CMA, as it did at other institutions.

In contrast to some other museums, Cleveland’s collection is largely the result not of gifts, with obvious exceptions, but rather of purchases that were matters of curatorial discretion. In terms of its sources, the collection may be unusual in its midcentury dependence on a single dealer and the friendship to which that dependence owed. It also may be unusual in the involvement of so many women in its formation, Norweb first among them but also Bole, Ford, Humphreys, Ingalls, Rankin, Taft, and others. The motivations for their engagement with ancient American arts are not recorded but may have had to do, in part, with affordability, as Norweb once implied. Their interest could also have had roots in the Euro-American tendency to affiliate women, as well as the racialized Other, with material that the West pejoratively classified as decorative arts, or crafts, including the elaborate ceramics, textiles, and personal ornaments of the Americas.58 It is hoped that the present volume, the first of its kind, will shed more light on these and other factors that have shaped US museum collections over the last century.

Addendum: Other Ohio Collections of Ancient American Art

Among other collections in Ohio, the largest and finest is at the Dayton Art Institute. In round numbers, permanent holdings comprise 170 works of art that are supplemented by 120 objects on loan since 2000 from the foundation of the late Dayton philanthropists Harold W. and Mary Louise Shaw. The permanent collection, the result of gifts and purchases since the 1930s, incorporates a range of styles from both the Andes, including a rare Wari inlaid conch shell trumpet (1970.32), and Mesoamerica, with strength in the Maya, notably a carved stone panel depicting an enthroned couple (1970.37). The Shaw collection, which is said to have been assembled by the early 1970s, focuses first on Mesoamerica, again especially the Maya—another stone panel features a standing couple (L8.2001.105)—followed by the Isthmian Region.59

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Ashland University in Ashland, Ohio, accepted several ancient American donations that have not been described but are made up at least in part of Andean ceramics. Information about the Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection is likewise limited, but holdings seem to comprise about one hundred ancient Andean objects, one-third of them acquired in an early purchase, in 1883, and the rest by subsequent gifts.60 Most of the 150 ceramic works at the Columbus Museum of Art represent Mesoamerican styles, especially west Mexican, some purchased in the 1980s and earlier; among several gifts are fifty works from the collection of Eva Glimcher, cofounder with her son, Arne, of New York’s Pace Gallery. The styles of the seventy objects at Oberlin College’s Allen Memorial Art Museum range from Mexican to Peruvian; half, including many fragments, belong to a study collection. The Toledo Museum of Art’s principal ancient American holdings are some eighty ceramic vessels from Panama’s Chiriquí region; the majority were donated in 1907 and come from Yale University’s Peabody Museum, which deaccessioned them as duplicates, a common early practice.61 This summary omits Latin American ethnographic collections.

I thank Amanda Mikolic, former curatorial assistant, and CMA archivists Leslie Cade, Susan Hernandez, and especially Rebecca Tousley for their cheerful assistance with research for this essay.

Notes

-

Evan H. Turner, “Overview: 1917–30,” in Object Lessons: Cleveland Creates an Art Museum, ed. Evan H. Turner (Cleveland Museum of Art, 1991), 22. ↩︎

-

Allen H. Eaton, Handicrafts of New England (Harper & Brothers, 1949), 281–94; Bruce Robertson, “Frederic A. Whiting: Founding the Museum with Art and Craft,” in Turner, Object Lessons, 32–59. ↩︎

-

Monica Obniski, “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2008, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acam/hd_acam.htm. ↩︎

-

Robertson, “Frederic A. Whiting,” 38. It is curious that Whiting claimed pride of place for the CMA in the 1920 resolution since the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where he had lived, acquired its first ancient American textiles in 1878. ↩︎

-

Accessions Committee minutes, May 17, 1923, and March 24, 1925, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives (CMA Archives). ↩︎

-

“In Memoriam,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 46, no. 8 (1959): 181. ↩︎

-

Accessions Committee minutes, December 9, 1930, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

C. F. R., “Ancient Peruvian Pottery,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 18, no. 2, part 1 (1931): 35–38. ↩︎

-

See Neal Harris, “Thomas Munro: Museum Education 1931–67,” in Turner, Object Lessons, 126–35. ↩︎

-

Henry Hawley, “Directorship of William M. Milliken,” in Turner, Object Lessons, 101–22. ↩︎

-

Milliken reflects on Norweb and other donors in William Milliken, “The Cleveland Museum of Art Collection,” unpublished manuscript [1960s?], CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

“Holden, Liberty Emery,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, accessed September 5, 2024, https://case.edu/ech/articles/h/holden-liberty-emery. ↩︎

-

Mary Strassmeyer, “Norwebs Mark 50th Anniversary,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 15, 1967, p. 18-E. ↩︎

-

Wilma Salisbury, “The Flamboyant Collector,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 11, 1970, 1, p. 8-E. Norweb collected widely, but her main interest was numismatics. ↩︎

-

In the 1950s, Samuel K. Lothrop, archaeologist at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, agreed to have Peabody staff survey Norweb property on Panama’s Azuero Peninsula with the understanding that the CMA would receive any exhibitable ancient objects that might result. The property, however, could not be accessed. See 1951–52 letters among Lothrop, Norweb, and Milliken, Administrative Correspondence of William M. Milliken, R. Henry and Emery May Norweb, 1930–1958, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

The count overlooks twenty-four necklaces made of restrung Andean beads. ↩︎

-

Milliken, “The Cleveland Museum of Art Collection,” 146, and Salisbury, “The Flamboyant Collector,” for the story of Milliken’s first, enthralled encounter with Norweb’s textiles. ↩︎

-

CMA records for her gifts are spotty, and her papers, in the library of Cleveland’s Western Reserve Historical Society, contain no information about her collection. ↩︎

-

Michael Coe, “From Huaquero to Connoisseur: The Early Market in Pre-Columbian Art,” in Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past, Elizabeth Hill Boone, ed. (Dumbarton Oaks, 1993), 271–90. ↩︎

-

Milliken, “The Cleveland Museum of Art Collection,” 144–45. ↩︎

-

John Canaday, “Behind Exciting Art Show: A Little-Known Collector,” The New York Times, January 2, 1969, p. 34. ↩︎

-

Wise’s papers at the Dallas Museum of Art, which I have not examined, likely have more light to shed on his relationships in Cleveland. ↩︎

-

Milliken, “The Cleveland Museum of Art Collection,” 147; also see Turner, Object Lessons, 123. ↩︎

-

Administrative Correspondence of William M. Milliken, Helen Humphreys 1943–1957, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Milliken, “The Cleveland Museum of Art Collection,” 150. In his final days, Hanna asked for the loan of five ancient American gold objects the museum had purchased from Wise so he could enjoy them at home. Board of Trustees minutes, January 17, 1957, 5, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Exhibition Compendium, Milliken to Wise, January 19, 1946, and Milliken to A. E. Parr, August 18, 1945, among others, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Coe, “From Huaquero to Connoisseur,” 271, 286. ↩︎

-

Exhibition Compendium, Rambova to Milliken, December 15, 1945, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Milliken, “The Cleveland Museum of Art Collection,” 144. ↩︎

-

For Milliken’s mood extremes, see Hawley, “Directorship of William M. Milliken,” 101; for the textiles encounter, see note 17. ↩︎

-

For instance, Henry Hawley, “Pre-Columbian Art at Cleveland,” Apollo 78, no. 22 (1963): 489–93; Sherman Lee and William D. Wixom, “In Memorial: William Mathewson Milliken, 1889–1978,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 65, no. 4 (1978): n.p. ↩︎

-

Evan H. Turner, “Overview: 1945–58,” in Turner, Object Lessons, 96–100; Hawley, “Directorship of William M. Milliken,” 113. ↩︎

-

Katharine Lee Reid, personal communication with the author, ca. 2004. ↩︎

-

Hawley, “Directorship of William M. Milliken,” 115. ↩︎

-

William Milliken, “Exhibition of the ‘Art of the Americas,’” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 32, no. 9 (1945): 155–71, 175, and “Part II. Annual Report Issue for the Year 1945,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 33, no. 6 (1946): 107. ↩︎

-

“Before Columbus: Gold, Stone, and Wool at Cleveland,” ARTnews 44, no. 16 (1945): 20–23; Milliken, “Exhibition of the ‘Art of the Americas,’” 155. ↩︎

-

“Before Columbus,” 20. See exhibition photos on the CMA Archives’ website, accessed September 5, 2024, https://www.clevelandart.org/ingalls-library-and-museum-archives/historical-exhibitions?search=Art+of+the+Americas&page=0. ↩︎

-

For instance, Milliken, “Part II. Annual Report Issue for the Year 1945,” 107. ↩︎

-

Exhibition Compendium, Milliken to Norweb, December 5, 1945, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Exhibition Compendium, Howard to Harold T. Clark, December 17, 1945, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Exhibition Compendium, Milliken to Robert Woods Bliss, January 6, 1947, CMA Archives. The booklet seems to omit some of the objects that appeared in the exhibition. ↩︎

-

Administrative Correspondence of Sherman E. Lee, Series 1, Lee to Wise, September 6, 1958, CMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Sherman E. Lee, “The Cleveland Museum of Art: 1958–1983,” in Turner, Object Lessons, 163–81. However, acquisition funds greatly increased in 1957 after half of Leonard Hanna’s $34 million bequest was devoted to art purchases. ↩︎

-

In retirement, Milliken remained in touch with Wise (see figure 9) and wrote the foreword to the catalog for an exhibition, World of Ancient Gold, that Wise organized at the New York World’s Fair in 1964–65. Wise bequeathed his collection and papers to the Dallas Museum of Art. According to the late, long-time Dallas curator Carol Robbins, however, the Wises had always anticipated that their collection would find a home in Cleveland (personal communication with the author, June 12, 2007). The shifting wind that followed Milliken’s retirement in Cleveland likely explains their change of mind, at least in part. ↩︎

-

Clemency Coggins, “Illicit Traffic of Pre-Columbian Antiquities,” Art Journal 29, no. 1 (1969): 94, 96, 98, 114. ↩︎

-

Hawley memo, ancient Americas departmental files, 1970s, CMA. ↩︎

-

Exhibition Compendium, Turner to Mary Miller, Linda Schele, and lenders, late 1986 and early 1987, CMA Archives. The collaboration may have been prompted by the fact that the CMA and the Kimbell have companion stelas from the Maya site Waka’ (see figure 13, Kimbell AP 1970.02). ↩︎

-

Margaret Young-Sánchez, personal communication with the author, 2024. ↩︎

-

Margaret Young-Sánchez, “The Gruener Collection of Pre-Columbian Art,” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 79, no. 7 (1992): 234–75; James C. Gruener, The Olmec Riddle: An Inquiry into the Origin of Pre-Columbian Civilization (Vengreen Publications, 1987). The education art collection contains 104 additional Gruener objects. ↩︎

-

Young-Sánchez to Diane De Grazia, “Collecting Philosophy” memo, March 3, 1998, Ancient Americas departmental files, CMA. ↩︎

-

Young-Sánchez, personal communication with author, 2024. ↩︎

-

Young-Sánchez, “Collecting Philosophy” memo. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Katharine Lee Reid, personal communication with the author, ca. 2000. ↩︎

-

The acknowledgment can be found on the museum’s website, accessed September 5, 2024, https://www.clevelandart.org/indigenous-peoples-and-land-acknowledgment. ↩︎

-

In the mid-1950s, during Sherman Lee’s directorship, scores of Native North American objects in the permanent collection were transferred to the education art collection, over Henry Hawley’s objections. Memo from Hawley to Gabriel Weisburg, October 1974, ancient Americas departmental files. That trend was reversed in the 2000s; also, Young-Sánchez acquired several North American objects in the 1990s. ↩︎

-

For instance, Martin Berger, “Introduction” and “Between Canon and Coincidence,” Journal for Art Market Studies 7, no. 1 (2023), https://fokum-jams.org. ↩︎

-

For instance, see Elissa Auther, “The Decorative, Abstraction, and Hierarchy of Art and Craft in the Art Criticism of Clement Greenberg,” Oxford Art Journal 27, no. 3 (2004): 339–64. ↩︎

-

Harmer Johnson, “Introduction,” Dayton Art Institute, Pre-Columbian Treasures: The Harold W. Shaw Collection (Dayton Art Institute, 2003). My thanks to Sally E. Kurtz, the institute’s registrar, for kindly supplying information about Dayton’s collection. ↩︎

-

This estimate comes from an unillustrated spreadsheet provided by the museum. Tamara Bray determined that most of the Ecuadorian objects at the University of Cincinnati’s Langsam Library are replicas. Personal communication with the author, 2024. ↩︎

-

“Chiriquian Pottery,” a notice of acquisition in Toldedo Museum of Art files. ↩︎