In the 1960s and 1970s, the Tucson Museum of Art found new clarity in defining a vision of its future. After decades of operating without a permanent collection, doing business under various organizational names, and mounting an eclectic range of exhibitions in rented quarters, the museum began to push for a building of its own and to plan for an art collection, and what was then called “pre-Columbian art” was foregrounded as central to its purpose. Reporting on a gift of funds to construct the new galleries, the Arizona Daily Star noted that “the new museum is expected to feature permanent collections of pre-Columbian, Spanish Colonial, and contemporary Western art,” observing the special relationship between the museum’s collection-to-be and Tucson’s identity as a place of Mexican heritage.1 Museum leadership believed that Tucson’s history should guide their acquisitions, and the art of the Americas—and especially ancient and colonial art from Mexico—became the institution’s foremost priority.

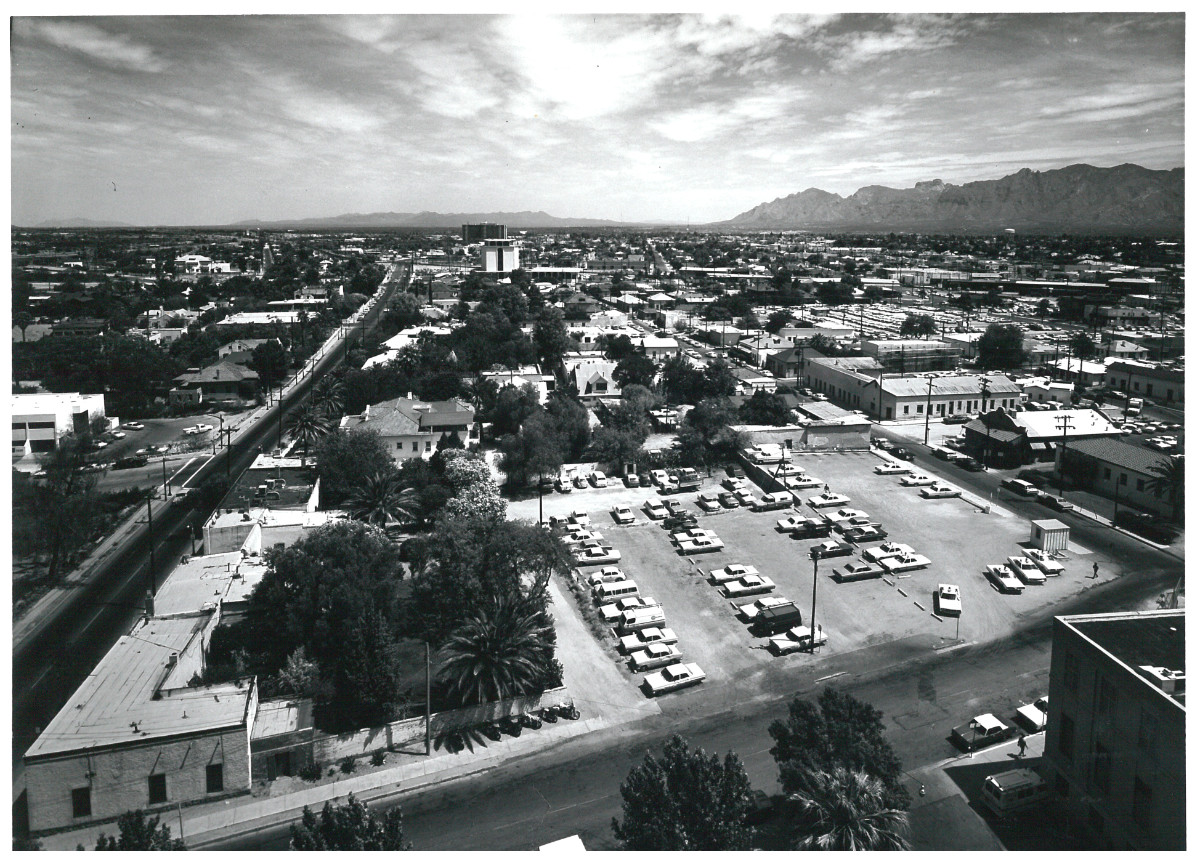

This plan and mission for a new museum, however, were born within a complex political and social reality. Tucson in the 1960s was a city in transition. Policies were enacted that would fundamentally change the identity of downtown, where the museum’s campus would ultimately be built. An urban renewal plan, approved by Tucsonans in the mid-1960s, would condemn and clear the neighborhood known as la calle, where Mexican Americans and Mexicans had built a busy and culturally connective commercial and residential district. In its place, city leaders envisioned that new cultural spaces would “modernize” Tucson, reconfiguring city blocks to eliminate these homes and businesses and displace their residents. In short order, the new museum, with its mission of collecting Tucson’s Mexican past, would come to occupy a space within that urban renewal footprint.

Tucson is a Borderlands place, and because of this, new initiatives can only intervene within a landscape that has been multiply reinscribed across the region’s deep history.2 Tucson is on the ancestral territory of Indigenous Sonoran Desert communities. Southern Arizona was not part of a US state but a territory until 1912, remaining so for more than sixty years after California’s statehood, and it was Mexican territory until the Gadsden Purchase of 1854. The city is only an hour’s drive north of the border, and its built environment and visual culture through the mid-twentieth century were defined by Tucson’s relationship to Mexico. The Presidio, built to house New Spain’s armies, once anchored the city center, and in the surrounding neighborhoods, Sonoran-style adobe structures housed downtown Tucson residents and businesses. For all these reasons and more, Arizona historians suggest that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Tucson was largely perceived as Arizona’s “Mexican” town—unlike Phoenix, where Spanish and Mexican armies never settled and where anti-Mexican attitudes precluded what one scholar described as Tucson’s unmatched “bicultural vitality.”3

Today, many art museums across the country are increasingly attentive to amplifying the resonances between the objects that they steward and their local contexts. For institutions that collect ancient American art, collections are increasingly activated in collaboration with local Latinx and Indigenous communities and their histories. At the time of the collection’s founding, Tucson Museum of Art leadership imagined that they would build a collection tied to regional histories, acquiring works intentionally for their ties to local people and place. Even so, closely attending to the historical conditions in which that collection was formed traces a more nuanced story about the relationship between the museum and community. Most recently, this history also includes initiatives in which the museum has sought to chart a path forward in new, inclusive relationships with communities.

Turning momentarily to the first person: I worked at Tucson Museum of Art as curator of the Latin American collections from 2019 to 2024, where my colleagues and I were sensitive to both the unique circumstances of the museum and the distinctive relationship of the institution to its local context. The museum is different in key ways from the other institutions whose histories are studied in this volume. Its collecting began relatively late, with the first acquisitions of ancient American art coming only in 1965. It has never been an encyclopedic museum, and so the ancient American collections have never been asked to justify their importance relative to other global ancient traditions. There are also operational differences: The museum’s campus is small, its staff lean, its resources modest. Yet even given these differences, the Tucson Museum of Art’s history is important to the broader picture of how ancient American art has been collected and exhibited in art museums in the United States. Its history tells how stewarding ancient American art became entangled in a city’s broader renegotiation of its own identity as a place of Mexican history, heritage, and culture.

Ancient American Art in Tucson Before the Tucson Museum of Art

Long before the Tucson Museum of Art began acquiring objects for its permanent collection, Tucsonans maintained broad popular interest in the ancient Americas and in their city’s relationship to the Mesoamerican past. The origins of the connections between southern Arizona and Mesoamerica run deep. Iconography from historical pottery of the Southwest shows that by the 1300s, Indigenous artists of southern Arizona created imagery representing ideologies shared with Mesoamerican peoples, with common ideas and images circulating beyond the delimitations of contemporary national borders.4 Today, Indigenous collaborators in Tucson Museum of Art curatorial projects continue to affirm ties between southwestern heritage and ancient American visual cultures, recognizing a common heritage in Mesoamerican art.

Newspaper records of the early twentieth century show that English-language audiences were interested in Tucson’s ties to Mesoamerica—though the most spectacular account in this early history was rooted in an archaeological fraud. In 1924, a trove of lead crosses, swords, and other artifacts was discovered by the city’s deputy sheriff while he explored a lime kiln near a wash a few miles from downtown. Dozens of additional objects were soon uncovered, several of which were inscribed with Latin texts that were later proven to be haphazard copies lifted from the classics. For years, local authorities speculated that the artifacts might prove that Tucson was the meeting place for ancient Toltec and Roman soldiers, and no less a figure than George Vaillant (1901–1945), then curator at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, was brought to inspect the find site.5 The question of their authenticity was at last debunked by 1930, but the forgeries effectively generated years of local interest in Tucson’s ties to Mesoamerica and the broader world.

Indeed, Americanist archaeology played a significant role in defining the regional identity of Tucson in the 1930s. In the words of one reporter writing in the Tucson Daily Citizen in 1937, “One of the strongest lures of the Southwest is the historically fascinating field it offers to the archaeologically minded. Not only does this region provide limitless resources to the scientist, but the layman is ever conscious of the ‘great discoveries’ as is demonstrated by the many bones, pieces of pottery and other objects which are turned into the State Museum for inspection.”6 Popular media brought news of excavations carried out in Pueblo archaeology in northeastern Arizona, while the Arizona State Museum in Tucson processed accumulations of scientific and informally excavated materials.

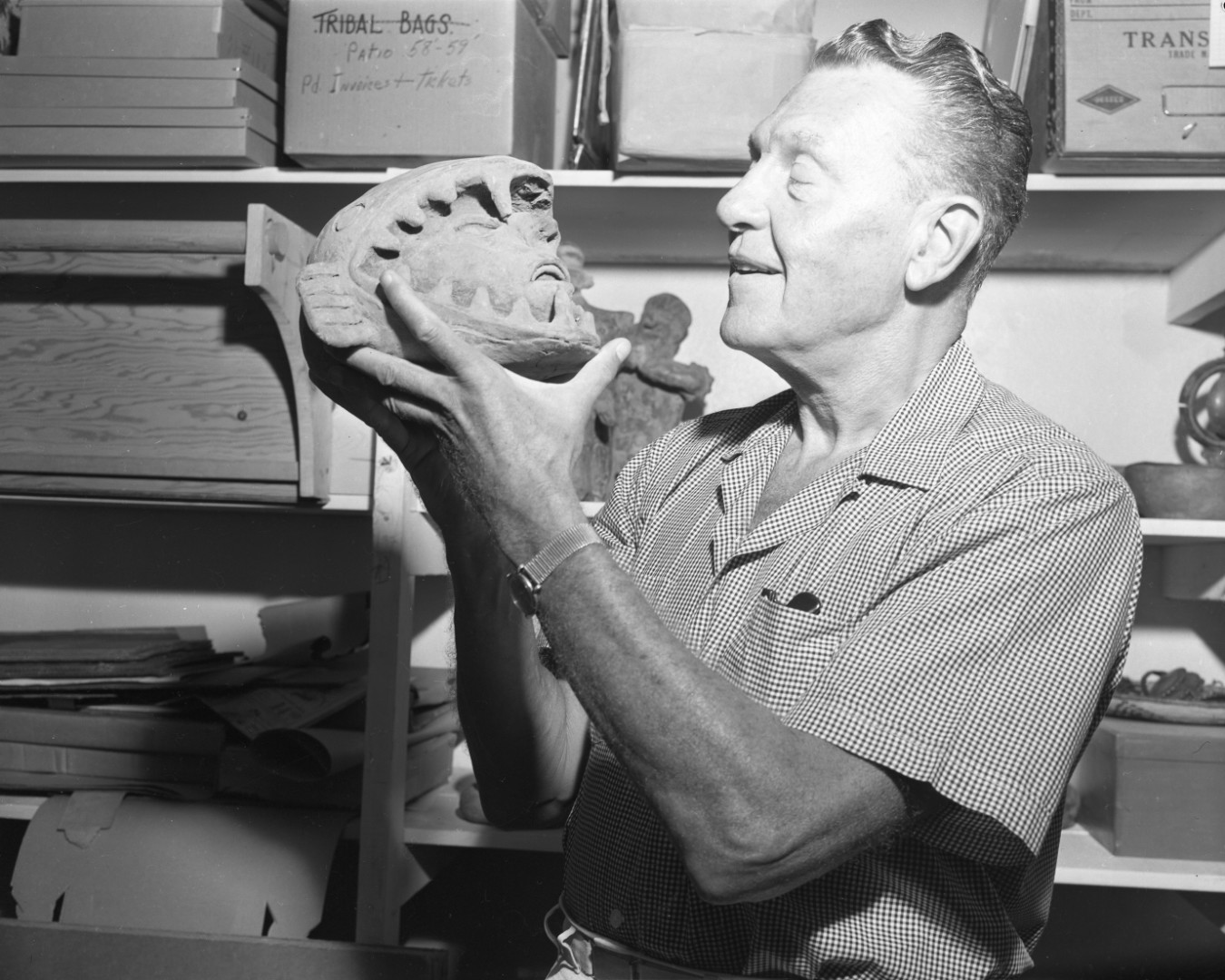

While Tucsonans’ interest in the archaeology of the ancient Americas is clearly attested in the early decades of the twentieth century, sources on ancient art’s commercialization during the same years are relatively quiet. By midcentury, however, several galleries that specialized in ancient American art operated in the city. Sheep rancher Clay Lockett (ca. 1906/1907–1984) opened his Indian Arts and Crafts shop in 1942, marketing ancient American art and works in other collecting categories to a Hollywood clientele. A photograph documents a visit by actor Ralph Bellamy (1904–1991), who is shown holding an ostensibly pre-Columbian ceramic work that he purchased at the gallery (fig. 1). Oral histories recall that noted collector Vincent Price (1911–1993) also paid a visit to Lockett in search of ancient gold objects in the early 1960s.7

Lockett was not alone in selling pre-Columbian art in midcentury Tucson. Promotional announcements for galleries now long defunct evidence the active trade in ancient American artworks in the city. At a gallery called Shearman-Sierk, photographs from 1962 document an installation in which west Mexican sculptures hung alongside paintings by local artists in the gallery’s inaugural exhibition, designed by the University of Chicago–trained art historian Richard Pelham-Keller.8 Another gallery, America West Primitive and Modern Art, sold pre-Columbian art under the direction of Tucson-born Princeton graduate Kelley Rollings (1927–2018), who also offered works in other categories to meet local interest.9 Also in town was Catherine Noble’s Mexican Shop, where 1956 saw a sale of “effigies and bowls recently brought back from the Nayarit district.”10 Decades later, the proprietors of several of these local galleries would play a pivotal role in growing the museum’s collection: Both Lockett and Rollings would donate to the museum’s Latin American holdings, with Rollings gifting Mesoamerican works to the growing collection in the 1970s.11

Cumulatively, available sources suggest that in midcentury Tucson, ancient American objects were largely marketed and displayed as part of a cross-category decorative collecting practice, bought and sold alongside what today we distinguish as colonial Latin American art, Indigenous southwestern works, Latin American folk art, and even art of the American West. Interior photographs of Tucson homes suggest how consumers in this market displayed these works together. Images show ancient American objects like Nayarit figural sculpture displayed alongside Mexican silver in colonial styles and Indigenous historic pottery from the US Southwest.12 The cross-category mingling of ancient American objects reflected in such collection photos mirrors their movement through the market.

In the same years when Tucson dealers and purchasers shaped a collecting practice for the region, Tucson-area institutions were also defining serious scholarly commitments to scientific study of ancient Mexico. New learnings from these projects identified scientific bases for shared histories between Mesoamerica and the Southwest. East of the city, the Amerind Foundation’s director, Charles Di Peso (1920–1982), was engaged in excavations at Paquimé, Chihuahua, from the late 1950s into the 1960s in partnership with Mexico’s INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia). Di Peso’s excavations established that Paquimé was a point of high-volume trade between Mesoamerica and the Southwest, a place where scarlet macaws from Mesoamerica were husbanded in the Chihuahua desert.13 More broadly, the Amerind’s projects were staking out a vision in which Arizona and New Mexico might be posited as Mesoamerica’s northernmost expression.

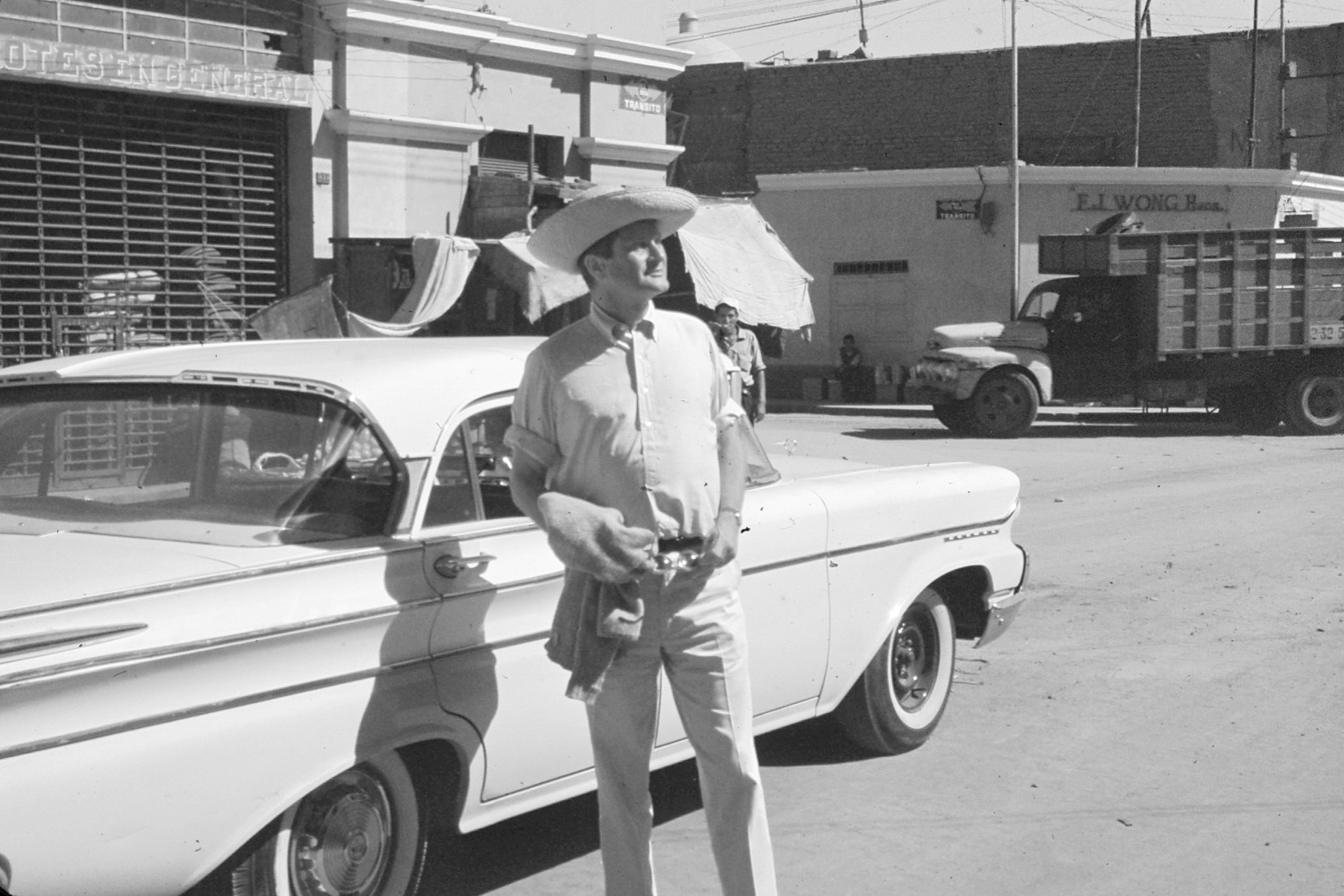

The local conditions described thus far—gallery sales of pre-Columbian art, a decorative style incorporating ancient American objects, extensive local reporting in the popular press on Arizona Americanist archaeology, and archaeological excavations tying the Southwest to Mesoamerica—all had a part in defining Tucson’s relationship to the ancient Americas. Yet none of this might necessarily have led to the creation of a local museum collection of ancient American art. There was, after all, no clear space for such a collection. The University of Arizona Museum of Art had been energized in 1951 by a gift of Renaissance paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation; meanwhile, its civic analog, the Tucson Fine Arts Association, which would later become the Tucson Museum of Art, would not begin collecting in any category until 1959. But that first gift would come from Frederick Rhodes Pleasants (1906–1976), a prodigious collector, curator, and heritage worker who became a leading force in the city’s cultural sector (fig. 2). Singly, Pleasants would become the figure most responsible for the institutionalization of ancient American art history in the city.

Frederick R. Pleasants and the Founding of the Tucson Museum of Art Collection

Before arriving in Tucson, taking a position at the University of Arizona to enjoy the health benefits of the desert, Pleasants had developed a multifaceted career in museums and heritage work. Trained at Princeton University as a specialist in Maya art and archaeology, Pleasants organized exhibitions at Harvard’s Peabody Museum in the 1930s, where a report from the institution states that one display on the Americas emphasized “the effect of environment on culture.”14 World War II brought Pleasants to issues of restitution: As a Monuments Man, he was appointed to head the Central Collecting Point in Munich in 1946. His return from the war also brought him back to the Peabody, and then to the Brooklyn Museum, where he succeeded Herbert Spinden (1879–1967) as Curator of Primitive Art from 1949 to 1956.15

During the Brooklyn years, Pleasants organized exhibitions that perhaps best speak to his vision of the field. In a short bulletin published by the museum, he laid out a plan for the department that distinguished between what he termed “objects of art” and “objects of anthropology.” Brooklyn would pay most attention to art, with the purpose of working to “demonstrate the special contribution of primitive art, its closeness to technical processes, and its strongly motivated social background as well as showing the best from an aesthetic viewpoint.”16 In his galleries, Pleasants grouped Aztec works with African and Oceanic objects to suggest that all works had social motivations. Visually, he pursued what he described as “experimental display techniques” with modern lighting and harmonious color schemes. A bibliographic note tells us that in 1954, Pleasants spoke at a Wenner-Gren Foundation Supper Conference alongside Alfred Kidder (1885–1963) and Linton Sattherthwaite Jr. (1897–1978) where the topics included, among other things, “The Role and Function of Museums,” “Problems of Exhibition,” and “The Potentialities of Television.”17

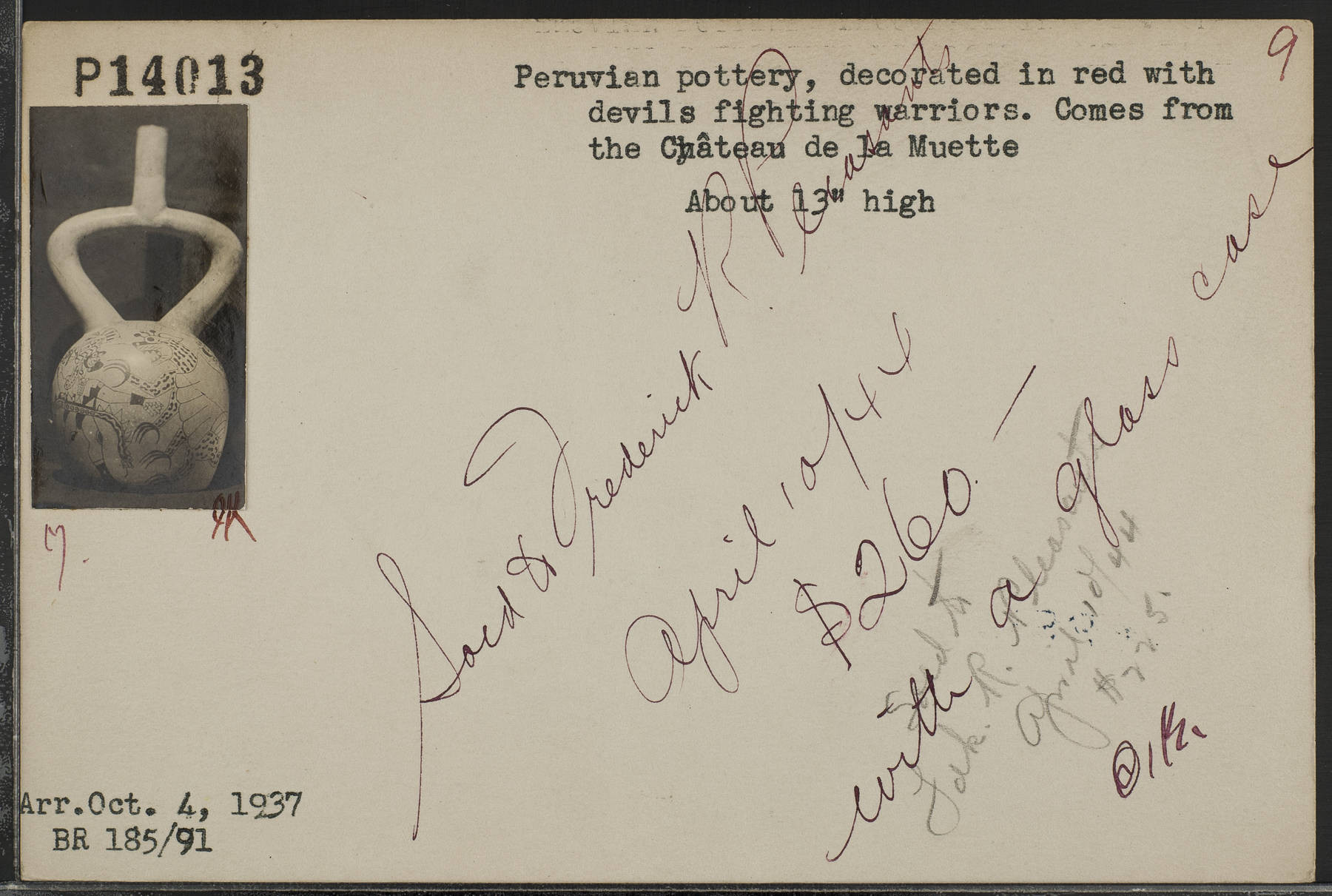

Alongside his museum work, Pleasants was also building a personal collection. By his own account, he was motivated to collect “primarily for teaching purposes,” an assertion that aligns with his relatively pedagogical approach to presenting museum galleries.18 The timeline and methods of his acquisitions, however, remain obscure. By 1938, Pleasants’s name would be recorded as a purchaser in the Brummer Gallery records, and in 1944, Brummer sold Pleasants a Moche vessel now in Tucson’s collection (fig. 3). A textile in a hybrid Moche-Wari style (2001.23.1), also now at the museum, was almost certainly owned previously by one of Pleasants’s Brooklyn contacts, the German Peruvian dealer Guillermo Schmidt Pizarro (1880–1964), who sold a related work to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in the 1930s.19 Later in the Brooklyn years, Pleasants would also make his most significant purchase, acquiring in 1950 a monumental stone sculpture from Veracruz from gallerist Pierre Matisse (1900–1989), who had been one of Pleasants’s contacts during his years at the Peabody (fig. 4).20 Similar in style to the Lápida de Tepatlaxco, itself created in the first millennium CE in an area near Orizaba, Veracruz, the sculpture sourced from Matisse has now been identified as among the first works to be sold by artist Diego Rivera (1886–1957) on the international art market.21 Matisse may also have been the source for another Pleasants work, a stone palma from Veracruz that was previously owned by governor of Veracruz Teodoro Dehesa Méndez (1848–1936; fig. 5).22 Today, we know that Dehesa’s relative had entrusted a number of sculptures to Matisse for sale, suggesting that he could have been the source for the Pleasants palma as well.23 This collection of details about specific acquisitions surely underlies a broader picture of Pleasants as a collector, although that picture remains to be further clarified.

While Pleasants’s collecting patterns are only beginning to emerge, what is better documented is the sensational impact of the collection once its owner moved to Tucson in 1958. Soon thereafter, the Arizona State Museum mounted a 1962 exhibition of his holdings. The show was accompanied by a published catalog with listings of many of the definitive works from his collection, suggesting that by that year, most of the major acquisitions had already been made.24 In the wake of the exhibition, Pleasants began transferring his collection to museums, and the Arizona State Museum received several important objects, including important Andean weavings. However, Pleasants evidently determined within a few years that many gifts from his collection should be routed toward an art-focused institution instead.

In 1965, Pleasants transferred the Veracruz sculpture that he purchased from Matisse to the Tucson Art Center, where he had taken a position on the board. This donation was a remarkable vote of confidence for an organization that at that point had a collection of fewer than forty artworks, almost all of which were works on paper. Even so, Pleasants envisioned that the center might become a serious place for the study of regionally significant art from periods before Arizona statehood. In his words, he saw “a great opportunity to develop a distinguished collection of both pre-Columbian and Latin American Colonial art and to have both permanent and temporary exhibitions of the finest examples of those arts characteristic of Tucson and the Southwest.”25 Loans of additional objects, and then additional gifts, followed: In 1972, Pleasants donated jades that had just been published by the Emmerich Gallery (fig. 6), a Chocholá-style vessel, and a Wari tapestry-woven tunic.26 Pleasants also donated the foundations of a research library, giving the young institution over two thousand scholarly volumes and thousands of slides.

To exhibit the Veracuz sculpture and other Pleasants objects, the Tucson Art Center quickly established a Primitive Art Room in its rented quarters at the historic Kingan House in downtown. Pleasants’s pieces were joined there by other loaned works from Tucson collectors, including dealer Rollings and Costa Rican art collector Frank Appleton. Because the gallery was small, Pleasants planned a quickly rotating exhibition to display a sequence of selected objects. For a few weeks, the gallery highlighted works from what he called “nuclear America,” which were then replaced by Costa Rican antiquities, followed thereafter by Andean textiles, and so on.27 These years saw the Art Center’s director, E. F. Sanguinetti (1917–2002), photographed in the Tucson Daily Citizen, posed in a near-embrace of the Veracruz sculpture to which he looked, in the words of the reporter, with “obvious pleasure.”28 As the institution’s collecting and exhibitions of ancient American art built momentum, subsequent directors expressed their elation at the prospect of making Tucson a center for ancient American art. One interim director, Gerrit C. Cone, remarked that the donation had inspired “a new faith in the Art Center, its program and its staff.”29

In those years, the Art Center’s leadership was clear about its commitment to forming what was envisioned as a “distinctive regional museum featuring the legacy of pre-Columbian and other primitive art, Spanish Colonial, Western, and folk art.”30 Rather than form an encyclopedic collection—an impossibility—the museum chose to foreground local relevance, focusing on areas important to the history of southern Arizona. Such a regional focus would still allow for international reach and collaboration. One hope was that when the museum managed to secure a permanent building, it might include a “Mexican Room,” a gallery for showing exhibitions organized by Mexican museums.31 Little more than a decade later, the museum’s board would back away from its regionalist focus.32 But in the late 1960s and early 1970s, ancient American and colonial Latin American art centered their vision for the future. Though it did not yet have a building, the institution had an identity: It would define itself by its commitments to Mexico and the Americas, conserving histories that made Tucson distinctive.

Enthusiasm for the Art Center’s mission and its formalization as a museum was helped along by observers from the outside. Dudley Tate Easby Jr. (1905–1973) and Elizabeth Kennedy Easby (1925–1992), then at work organizing The Metropolitan Museum’s monumental Before Cortés exhibition, came to Tucson in 1969 and spoke approvingly of the institution’s intention to focus on the ancient Americas. In Dudley Easby’s flattering comments to Tucson press, by prioritizing this area, “the center here would be doing what the Metropolitan Museum should have been doing for the past 97 years.” He did not hesitate to opine, though, on the intractable problem of financing the center’s transition into a professional museum, criticizing city government for failing to “face up to whether or not they want an art center and start planning how to support it.”33

A few years later, the Veracruz monument was photographed in the news once again, this time as it was uncrated following its return from Before Cortés (fig. 7). The loan was heralded as a triumph: A piece from Tucson’s new collection had shown alongside works from major international museums.34 The enduring question, though, was how the Art Center might grow into a more mature institution in its own right and secure a new, fixed home. True to its institutional identity, the museum would look to the ancient American collection as part of the strategy that promoted its growth. That growth, however, meant intervening in a downtown environment where Tucson’s identity as a Borderlands place was being renegotiated.

Urban Renewal and Tucson’s Ancient American Collection

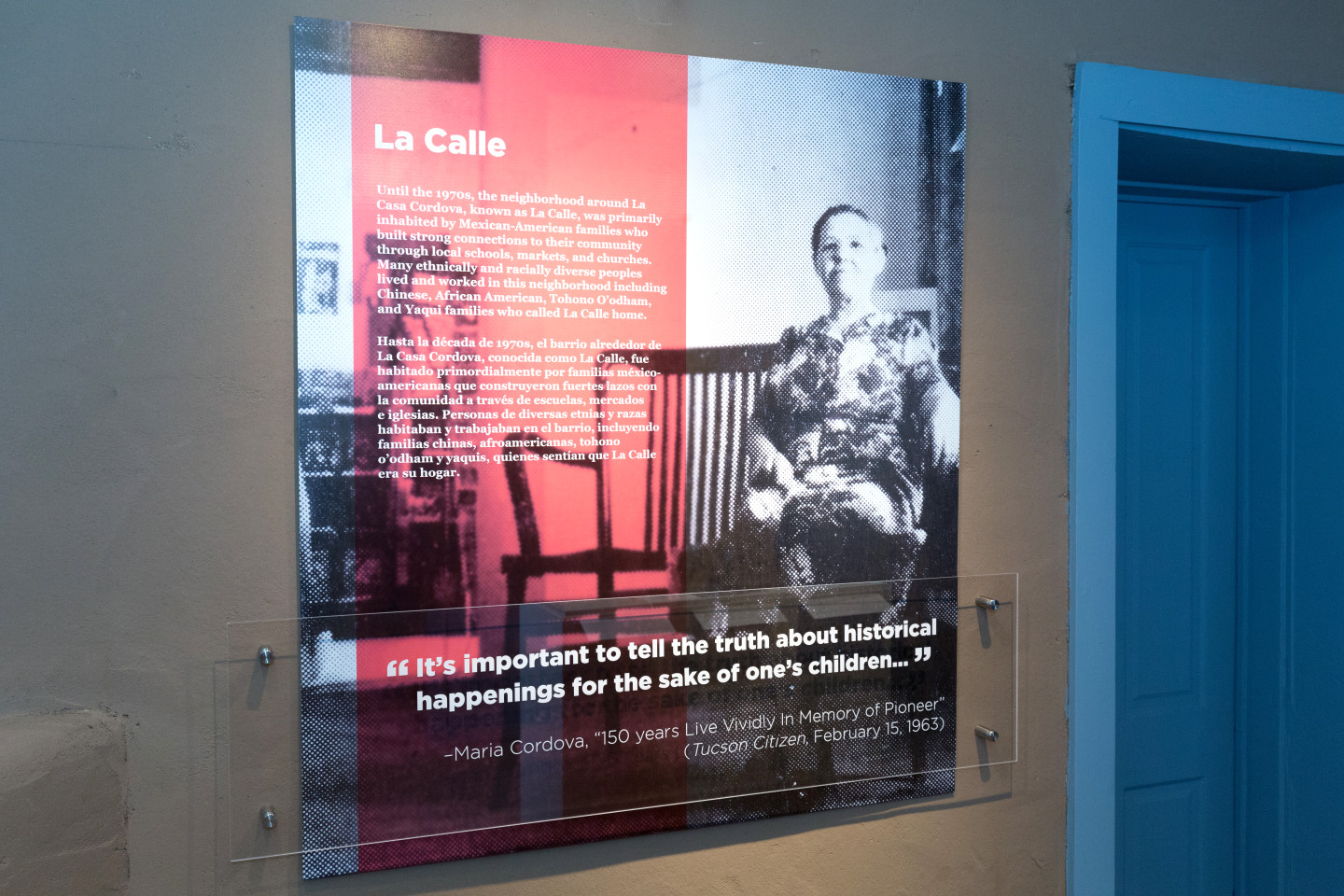

The years when the Tucson Art Center’s attention turned decisively to ancient American art were also pivotal years in the story of downtown’s changing identity. Until the mid-1960s, Mexican American and Mexican communities made downtown Tucson a busy urban center, alongside Indigenous and Chinese immigrant communities. In the district that residents called la calle—located around one of Tucson’s main thoroughfares of the time, Meyer Avenue—Mexican American Tucsonans ran businesses in mixed-use structures, some of which were built during the city’s Mexican period in the first half of the nineteenth century. Community spaces offered places to gather. La Placita, the community’s public square, hosted celebrations for patron San Agustín, and the nearby Plaza Theater screened Spanish-language films produced across Latin America.35

In 1964, however, the city of Tucson began working on an urban renewal plan that would displace most of the residents of la calle. In a meticulous study of the fate of the district, historian Lydia Otero noted both the process and rhetoric of this project. A decades-long effort had labeled the homes and businesses of downtown’s Mexican Americans as “slums,” preparing the way for their condemnation and removal. Cultural institutions were implicated in this plan; period documents suggest that the plan was that once the existing district was cleared, Tucson could rebuild with a “good cultural base,” in the words of the Commission on Municipal Blight.36

A number of influential voices opposed this plan. Otero has shown, for example, that the publisher of the Arizona Daily Star urged caution, writing: “Must the people of Tucson destroy this remaining area of former Mexican life just because the streets are too narrow and buildings old? . . . Maybe someday Tucsonans would look back at urban renewal and wonder why they authorized such a project which wiped out at one stroke what remained of Mexico in Tucson.”37 These concerns notwithstanding, voters approved the plan, and la calle fell to urban renewal. The essential votes passed in 1966, just months after the Art Center acquired its Veracruz sculpture.

The private Art Center’s need for a new space to meet its ambitions intersected with the city’s interest in building up a “cultural base” downtown, and director Sanguinetti began expressing his wish to benefit from the project to the press in 1965. If given a square block within the urban renewal footprint, he noted, the museum could “enrich community life and would provide a historical, psychological, and cultural focus around which the whole city might pulse.”38 Ultimately, for a rent of a dollar a year, the museum would be allowed to build within the boundaries of Tucson’s historic Presidio, dating to 1775 when Tucson was part of New Spain, at a site that had once held an ancestral pit house nearly two millennia ago (fig. 8).

The most visible architectural embodiment of Mexican history at the new museum’s site was the home occupied by María Navarrete Cordova (1896–1975) and Raúl Cordova (fig. 9). A Sonoran-style structure with architecture that partly predated the Gadsden Purchase, the Cordova House was the living home of a notable family of la calle. Through eminent domain, the city condemned the home, a decision that the Cordovas tried for years to reverse in court.39 As the museum took its place at the site, it would lease the Cordova’s home, becoming responsible for caring for the structure for the next one hundred years and planning gallery construction for the lot immediately adjacent.

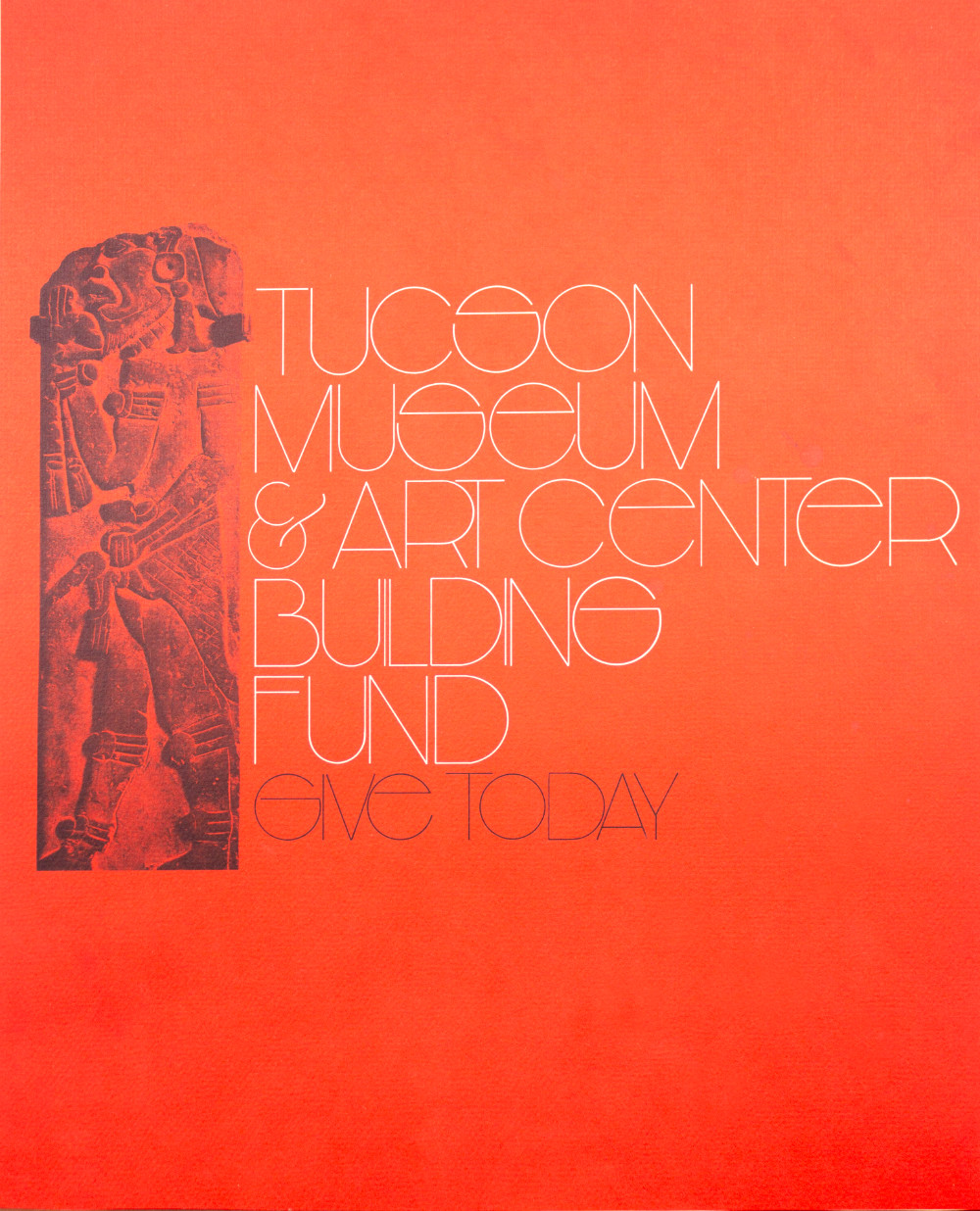

The Tucson Art Center was thus set on a path to build a home for its new collections at a place central to the Mexican identity of the city. Seeking funds to advance the project, ancient American artworks became the visual icons of the building fund, aligning the construction that would take place near the Cordova House with the image of a future home for the “pre-Columbian.” Pleasants’s Veracruz sculpture was the image selected for the poster soliciting financial support (fig. 10), and a drawing of the palma appeared on the sign that stood in front of the Building Fund’s downtown offices. The campaign’s iconography underscores that highlighting the museum’s ancient American collection was seen as the way to secure its future within the urban renewal footprint.

The new museum opened at last in 1975, and with it came a name change to the Tucson Museum of Art (TMA). Galleries featured artworks from Mexico, including works from the ancient Americas, and next door, the Junior League funded restoration to the Cordova House, converting it from a contemporary Mexican American home and commercial space to a period room of nineteenth-century Mexican Tucson, effectively erasing the experience of the home’s most recent residents.40

Urban renewal’s effects on Mexican American communities in Tucson were deeply felt, and the memory of this displacement is still articulated by community members today. Otero documents a sentiment often expressed in the city: Downtown left behind its Mexican American community, choosing to invest instead in an idea of an economically vigorous center that in reality failed to compete with the city’s suburban expansion.41

No single narrative neatly encapsulates the museum’s role in downtown’s changing identity. While the museum’s galleries and collecting looked to preserve material histories of Tucson’s relationship to Mexican identities and the ancient American past, that narrative was presentable only because the museum had benefitted from the urban renewal project. Conserving historical and ancient Latin American arts was, and remains, a meaningful project for communities of the Southwest, but the environment in which the spaces for the permanent collection were born broadly displaced Mexican American communities from participation in many aspects of downtown’s vitality. These conditions make showing ancient American art in the Borderlands distinctive: The collection resonates with the identity formation of local communities, but its presentation could only be possible through intervention into a landscape of layered histories and conflicting interests.

The museum early on sincerely embraced and played a role in fostering local Mexican American traditions, taking on projects that gave it a role in preserving the heritage of la calle alongside ancient American and colonial Latin American artworks. From its early years, it imagined itself as a place for Mexican Americans to gather. Every year beginning in the 1970s, Tucsonan María Luisa Tena and members of prominent Mexican American Tucsonense families organized a nativity scene, El Nacimiento, in the Cordova House, welcomed with a community procession. Tucson mounted exhibitions in its first decades of works by contemporary Chicano artists, and in 1992, it hosted the landmark exhibition Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation (CARA). These kinds of activities became part of a new image of cultural identity in Tucson, in which the ancient American collection played a part, though spatial tensions endured.

Later Years and Now

Over time, the museum’s relationship to its ancient American collections changed. By 1983, it appears that some board members had already begun to feel that the museum’s vision of a “distinctive regionalism” might have been too restrictive. An attempt to formalize the collecting policy to limit the museum to what it called pre-Columbian, Spanish colonial, and western art evidently met with displeasure, as an appetite was growing for the museum to embrace contemporary art. Director Andrew Maass was compelled to negotiate the identity of the museum in the press. He said, “I think we are a regional museum with a responsibility to present its collections and its exhibitions with a regional focus. . . . Here’s a regionalism for the West. I don’t think it’s anything to be scared of.”42 A new gallery for the ancient American collections was installed that year to great acclaim, expanding to a roomy new presentation in the finally finished building (fig. 11).43

In 2001, the museum installed a new presentation of ancient American art, positioning the field within a new conceptual frame, along with a historical architectural one. Artworks from Latin America, ancient to contemporary, were newly brought together and reinstalled in another of the Presidio’s historic houses, an adobe structure built in 1865. Reconceived by Joanne Stuhr, Americas curator from 1993 to 2003, the Latin American galleries emphasized Mesoamerican heritage as part of the Arizona-Mexico regional identity. The following year, Stuhr led TMA in originating an exhibition of Casas Grandes ceramics, Talking Birds, Plumed Serpents and Painted Women. The exhibition was a collaboration with INAH archaeologists and the Amerind Foundation that again emphasized the regional relevance of ancient Mesoamerican traditions. Latin American art projects were advanced in the following years by curators Stephen Vollmer (2004–06), Fatima Bercht (2007–09), and Anna Seiferle-Valencia (2010–12).

The end of the 2010s brought new approaches to the ancient American collection, as well as a reckoning with the history of the Cordova House. New galleries were planned for TMA’s ancient American collections, the first expansion of the museum’s physical footprint since 1983. Around the same time, the Cordova House was newly reinterpreted—this time, with the collaboration and cooperation of descendants of the Mexican American community affected by the urban renewal and with didactic panels explaining how urban renewal changed downtown Tucson. For the first time since its displacement, María Navarrete Cordova’s portrait returned to the Cordova House, reinserting the family and the memory of la calle into its narrative (fig. 12).44

From 2019 to 2024, I was responsible for TMA’s Latin American collections. The museum’s commitment to art from the region grew in those years with the construction and opening of the Kasser Family Wing of Latin American Art in 2020, a project that expanded galleries for the collection and focused exhibitions. Ancient American collections were foregrounded in the project, now expanded with gifts from I. Michael and Beth Kasser and Paul L. and Alice C. Baker. At the project’s outset, the museum’s approach to objects of heritage had already begun to evolve in light of the experience of reinterpreting the Cordova House and recontextualizing the Indigenous North American arts collections. Curating new ancient American galleries meant developing a project that created community participation, collaboration, and a polyvocal approach. Texts authored by community members with heritage relationships to the ancient Americas appear alongside exhibited objects, and curatorial interpretations have sought to amplify connections between works and the specific histories of Latinx communities in Tucson.

This approach has also characterized temporary exhibitions of ancient American art pursued in recent years. To take one example, the city became home to many Guatemalan refugees in the 1980s, and a 2023 exhibition Popol Vuh and the Maya Art of Storytelling presented ancient objects in light of the words of community members, who shared ideas about the relationship of narrative arts to heritage, alongside commissioned art by contemporary artist Justin Favela (fig. 13). A large-scale feature exhibition of Andean cloth, CUMBI: Textiles, Society, and Memory in Andean South America (2023–24) looked at weavings across time (including many donated by Pleasants) and displayed the work of contemporary textile artists of Andean heritage who practiced in or had ties to the Southwest. Today, the museum works to fulfill a vision of connecting ancient American art with Tucson’s community that was intended at the collection’s founding but with a new commitment to inclusion that charts the way forward.

In addition to thanking the editors of this volume and my fellow curators, I am grateful to my Tucson colleagues for generously sharing ideas or leads, including Marianna Pegno, Jennifer Saracino, Joanne Stuhr, Rachel Adler, Christine Brindza, and Erika Castaño, as well as the students in my University of Arizona course Aztecs and Incas for a lively discussion about this project. Special thanks are due to Deb Zeller, longtime steward of Tucson Museum of Art’s memory, for invaluable assistance in the archives. Any errors are my own.

Notes

-

Cathryn McCune, “New Museum Receives Gift of $500,000,” Tucson Daily Citizen, June 7, 1970, Top of the News section. ↩︎

-

In using the term “Borderlands” to describe the context of Tucson’s cultural politics, I invoke the work of theorist and poet Gloria Anzaldúa, with particular reference to her reflections on existence in this region in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (Aunt Lute, 1987). Anzaldúa’s work addresses the identity of subjects in relation to the geographic boundaries of national borders, as well as the shifting and emerging psychological and creative space of the region as informed by its intersecting, multiple histories. ↩︎

-

Thomas E. Sheridan, Los Tucsonenses: The Mexican Community in Tucson, 1854–1941 (University of Arizona Press, 1986), 42–43. ↩︎

-

Kelley Hays-Gilpin and Jane H. Hill, “The Flower World in Material Culture: An Iconographic Complex in the Southwest and Mesoamerica,” Journal of Anthropological Research 55, no. 1 (1999): 1–37; Andrew Turner and Michael D. Mathiowetz, ed. “Introduction. Flower Worlds: A Synthesis and Critical History,” in Flower Worlds: Religion, Aesthetics, and Ideology in Mesoamerica and the American Southwest (University of Arizona Press, 2021), 3–33. ↩︎

-

The New York Times reported that “the inscriptions have been interpreted as describing the conflicts of the prehistoric Roman-Jewish kingdom in the Southwest with the Toltec Indians, forerunners of the Aztecs.” “Puzzling ‘Relics’ Dug up in Arizona Stir Scientists,” The New York Times, December 13, 1925, p. 1. See also Don Burgess and Wes Marshall, “Romans in Tucson?: The Story of an Archaeological Hoax,” Journal of the Southwest 51, no. 1 (2009): 45. ↩︎

-

Betty McGrath, “Cummings’ 30 Years Research Results in Many Discoveries,” Tucson Daily Citizen, March 30, 1937, p. 7. ↩︎

-

Medicine Man Gallery, “Beverly Miller: Daughter of Trader Clay Lockett,” Episode 241, host Dr. Mark Sublette,” April 26, 2023, YouTube, 1:29:46, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SukNoyjTWY. ↩︎

-

“A New Gallery and New Shows,” Tucson Daily Citizen, January 20, 1962, p. 25. ↩︎

-

Charlotte Lowe, “America West’s Mix Is Eclectic,” Tucson Daily Citizen, April 11, 1991, p. 17. ↩︎

-

Beatrice Edgerly, “Center’s Show Traces Evolution of Hopi Indian Art and Crafts,” Arizona Daily Star, March 4, 1956, p. 31. ↩︎

-

Rollings’s donations included a painted Maya bowl (1976.212), Colima figurines (such as 1976.215), and Mezcala lapidary objects (including 1971.30), among other works. ↩︎

-

Barbara Smith, “The Dentons Chose a Perfect House for Their Indian Art,” Tucson Daily Citizen, October 29, 1960, p. 49. ↩︎

-

Charles Di Peso, Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of the Gran Chichimeca, vol. 2 (Amerind Foundation, 1974), 620–33. ↩︎

-

Seventieth Report on the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (Harvard University, 1937), 4. ↩︎

-

Anna Seiferle-Valencia, “Frederick R. Pleasants: A Curator and Steward of Pre-Columbian Art,” in Pre-Columbian Art: Selections from the Tucson Museum of Art Permanent Collection (Tucson Museum of Art, 2014), 23–31. ↩︎

-

Frederick R. Pleasants, “New Developments in the Department of Primitive Art,” Brooklyn Museum Bulletin 12, no. 2 (1951): 13. ↩︎

-

Evon Z. Vogt, “Anthropology in the Public Consciousness,” Yearbook of Anthropology (1955): 370. ↩︎

-

Frederick R. Pleasants, “Foreword,” in Primitive Art from the Collection of Frederick R. Pleasants (Arizona State Museum, 1962), n.p. ↩︎

-

Kristopher Driggers, CUMBI: Textiles, Society, and Memory in Andean South America (Tucson Museum of Art, 2023), 73–77. On Guillermo Schmidt Pizarro, see Carolina Orsini and Anna Antonini, “Life of a Peruvian Art Collector: Guillermo Schmidt Pizarro and the Fostering of Public Collections of Pre-Hispanic Art in the First Half of the 20th Century,” in PreColumbian Textile Conference VII, ed. Lena Bjerregaard and Ann Peters (Zea Books 2020), 258–77. ↩︎

-

Megan O’Neil, “‘Good Pieces in Sight:’ The US Market in Mesoamerican Antiquities circa 1940,” Gett Research Institute, June 15, 2022, YouTube, 1:25:58, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DM4WNudRCBA. ↩︎

-

Megan E. O’Neil, “The Changing Geographies of the Mesoamerican Antiquities Market Circa 1940: Pierre Matisse and Earl Stendahl,” in Collecting Mesoamerican Art Before 1940: A New World of Latin American Antiquities, ed. Andrew D. Turner and Megan E. O’Neil (Getty Research Institute, 2024), 310. ↩︎

-

Jesse Walter Fewkes, Certain Antiquities of Eastern Mexico (US Government Printing Office, 1907), plate 119; Tatiana Proskouriakoff, Varieties of Classic Central Veracruz Sculpture (Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1960), fig. 8. On Dehesa’s collecting and role in early studies of Veracruz sculpture, see Andrew D. Turner and Payton Phillips Quintanilla, “Collecting and Constructing Classic Veracruz: Earl Stendahl, Guillermo Echániz, and the Market for Mesoamerican Stone Ballgame Objects,” Journal for Art Market Studies 7, no. 1 (2023): 5. ↩︎

-

O’Neil, “The Changing Geographies of the Mesoamerican Antiquities Market Circa 1940,” 310. ↩︎

-

Primitive Art from the Collection of Frederick R. Pleasants (Arizona State Museum, 1962). ↩︎

-

McCune, “New Museum Receives Gift of $500,000.” ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Kennedy Easby, Pre-Columbian Jade from Costa Rica (A. Emmerich, 1968). ↩︎

-

Charlotte Cardon, “Pre-Columbian Culture Shown at Art Center,” Arizona Daily Star, November 7, 1965, p. 21. Unfortunately, no further archival materials are conserved that would suggest how Pleasants’s works were exhibited or what texts or supporting materials accompanied them. ↩︎

-

“Pre-Columbian Stele,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 4, 1966, p. 19. ↩︎

-

“As Skyline Changes, So Does Life in Tucson,” Tucson Daily Citizen, January 1, 1974, p. 17. ↩︎

-

“Rare Carving Returned After New York Exhibit,” Arizona Daily Star, January 26, 1971. ↩︎

-

“Architect Wilde Engaged to Design New Art Center,” Tucson Daily Citizen, February 17, 1970. ↩︎

-

An early mention of the board’s discontent with the museum’s regionalism of the institution appears in J. C. Martin, “Tucson Art Center: Its Beginnings. What Direction? At What Pace?” Arizona Daily Star, May 20, 1973, Section D, p. 3. ↩︎

-

Cathryn McCune, “City Owes Aid to Art Center,” Arizona Daily Star, January 13, 1969, p. 11. ↩︎

-

“Rare Carving Returned After New York Exhibit,” Arizona Daily Star, January 26, 1971, p. 17; Julie Sasse, Tucson Museum of Art: A Centennial History, 1924–2024 (Tucson Museum of Art, 2023), 77. ↩︎

-

Lydia R. Otero, La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City (University of Arizona Press, 2010), 127–52. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 112. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 105. ↩︎

-

“Museum Sought in Renewal Area,” Arizona Daily Star, August 27, 1965, p. 5. ↩︎

-

Lydia Otero, “New Directions for La Casa Cordova: Recentering the Latinx Past and Present in Tucson,” History News: The Magazine of the American Association for State and Local History 73, no. 3 (2018): 8–13. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 10–12. ↩︎

-

Otero, La Calle, 184. ↩︎

-

Kenneth LaFave, “Western Art Saddled by Its Own Reputation,” Arizona Daily Star, October 30, 1983. The conflict over the scope of collecting would ultimately lead to Maass’s departure. See Sasse, Tucson Museum of Art, 109. ↩︎

-

Kenneth LaFave, “Museum Remodel Worth the Wait,” Arizona Daily Star, October 30, 1983. ↩︎

-

Otero, “New Directions for La Casa Cordova,” 12. ↩︎