In the present day, nearly every curator of ancient American art in a US art museum has a strategic plan for their exhibitions, for acquisitions, and perhaps for programming and artist collaborations. Thoughtful collecting, display, and interpretation, directed by curatorial staff knowledgeable about their subject area, are hallmarks of twenty-first century museums. But things were quite different just a few decades ago. Many museums in the Mid-Atlantic region, like their New York and Boston counterparts, began to be formed in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries, a time when both curatorial training and study of the ancient Americas were in their infancy. This essay will show how collections at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore Museum of Art, and Philadelphia Museum of Art were shaped, not by curatorial concerns and strategy but by the actions of dealers, donors, and directors. Even as the study and knowledge of the ancient Americas expanded, few museums have had the luxury of full-time, permanent curators trained in this area. Of the institutions mentioned here, only the Walters has engaged a full-time, permanent curator for its collection (the author of this essay) and only in 2017. So, for decades, it was dealers, donors, directors, as well as fellows, conservators, registrars, and administrators who stepped in to help form, expand, and interpret collections and to organize exhibitions featuring art of the ancient Americas. Although this essay discusses museums of the Mid-Atlantic region, the pattern of other-than-curatorial administration can be extrapolated to a range of other museums that could not be covered by the 2023 Mayer Center symposium and this volume.

The Walters Art Museum

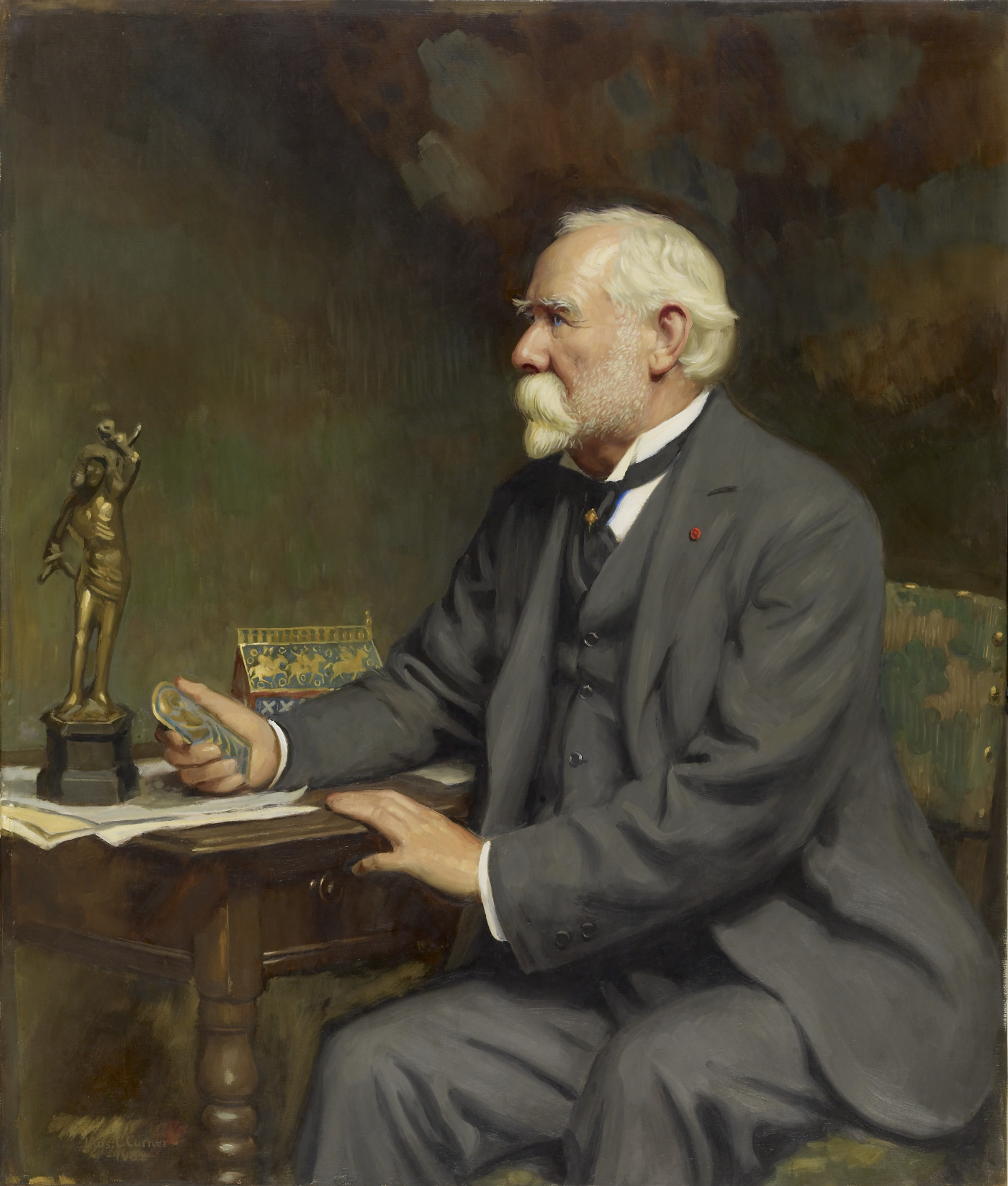

The influential dealer George Kunz (1856–1932) encouraged Henry Walters (1848–1951), the founder of the Walters Art Museum, to buy a range of works from Tiffany & Co., where Kunz was the first gemologist.1 While not a typical dealer with his own gallery, Kunz worked in various facets of Tiffany’s business for decades, but his role in marketing works of the ancient Americas, to Walters and other collectors, is still little-known. Kunz is recognized in this field only in connection with a jadeite figure held by the American Museum of Natural History in New York. One of the first works to be identified on a stylistic basis as Olmec, it is still known as the Kunz axe.2

Born in New York, Kunz became very interested in stones from a young age, after a formative visit to the mineral specimens at the Broadway Barnum Museum (fig. 1). Shortly after, he moved with his family to Hoboken, New Jersey, and began forming collections of the many rock types he was able to acquire there. He eventually sold a collection of minerals to the University of Minnesota, which gave him the confidence, at just twenty years of age, to offer a tourmaline for sale to Charles Louis Tiffany of Tiffany & Co. jewelers. At that time, only diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires, along with pearls, were typically used for jewelry. Kunz encouraged Tiffany to market a broader range of gemstones to a growing middle class. Tiffany hired him in 1876, and three years later, at just twenty-three years old, he became the company’s youngest vice president.3

At Tiffany, Kunz was able to form close relationships with many high-profile collectors of the period, such as J. P. Morgan and the Walters family of Baltimore. The founding patriarch was William Thompson Walters (1820–1894), but Kunz was especially close to William’s son Henry (1848–1931) (fig. 2). The family amassed great fortunes in a number of industries, particularly railroads. As Confederate sympathizers, though, they left Baltimore during the Civil War and lived in France where Henry was exposed to art from a young age. Over his adult life, he would make enormous additions to the modest collection begun by his father.4

It is not known how the paths of Henry Walters and George Kunz first intersected, but they certainly would have met by the time that Walters attended the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where he purchased items including at least one vase and a ring from Tiffany.5 As a plum marketing opportunity, it’s likely that Kunz would have also been present at the firm’s pavilion there. And Henry was not only a wealthy Baltimorean but maintained a residence in New York and served on the Executive Committee of The Metropolitan Museum of Art beginning in 1903, becoming a second vice president there in 1913, a position he would hold until his death in 1931.6

While Henry Walters’s extensive patronage of Tiffany & Co. has been documented, less well known is that Walters also bought about 120 works of ancient American art from Tiffany, likely through Kunz’s efforts.7 Unfortunately, none are as large or unusual as the Kunz axe, but the mere fact that Walters was purchasing such works for his own art collection was unusual for the time. Most of his acquisitions were jades or gold works from Colombia or Central America, objects that the gemologist acquired in his travels in search of new semiprecious stones to be marketed to US audiences. Kunz wrote about Colombian gold in an 1887 article for American Antiquarian magazine, at least a decade before Walters bought some of his first ancient American works.8 Walters’s first invoice from Tiffany for an ancient American work dates to October 1897, for a single silver “Peruvian chalice,” almost certainly WAM 57.977, followed by six Colombian gold works in November (figs. 3 and 4).9 After his 1897 purchases, Walters’s collecting slowed down, but in late 1910, he purchased from Tiffany five jadeite pendants from Central America and sixty-seven gold ornaments, which were shipped to his Baltimore home along with European objets d’art and gems.10 A letter of late 1910 from Tiffany clarified that these gold works were from the Chiriquí region of Panama, on the Costa Rican border.11 In late 1911, Walters purchased an additional twenty-eight gold works, said to be from Colombia.12

Kunz and Tiffany’s connection to this material is important in part because, although many museums are known to have Chiriquí gold objects acquired around this time—the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, National Museum of Natural History, Heye Foundation, Harvard’s Peabody Museum, and Yale University Art Museum, as well as several non-US museums—no one has yet traced their histories carefully to determine which of these works may have originated with Kunz.13

In that same year, Walters bought two Mexica (Aztec) central Mexican sculptures from the dealer Dikran Kelekian (1868–1951), who had galleries in Paris and New York.14 These are the only known ancient American works handled by Kelekian, but it is likely that he moved to profit from Walters’s interest. William Johnston, Walters’s curator emeritus and biographer of the Walters family, asserts that Walters’s curiosity was piqued by the French Exposition retrospective in the Trocadéro in 1878, at which “early Mexican terra cottas and sculptures captured the public’s imagination and conjured up such concepts as the lost content [sic] of Atlantis and prehistoric connections between Europe and America.”15

Johnston was probably correct in asserting that Walters’s interest in Central American gold and jades lay largely in their origins and craftsmanship as well as a desire to form a universal survey collection similar to that of The Metropolitan Museum.16 It is notable that during Walters’s term on The Met’s Executive Committee, the museum sent its own ancient American collections on long-term loan to the American Museum of Natural History, issuing a message that such works were not part of the “art” canon, as Joanne Pillsbury has noted.17 Yet, the two central Mexican stone statues purchased by Henry Walters, and to a lesser extent the golden works from Tiffany, continued to reverberate over the decades. The two stone works depict a rattlesnake knotted into a ball (fig. 5) and a seated figure with a tall, feathered headdress, likely the deity Macuilxochitl. Both had been part of the storied Pingret collection of ancient American art.18 Both were also included in Pál Kelemen’s Medieval American Art (originally published 1943), a key source when there were few published resources, particularly in English, available for scholars.19

The basalt rattlesnake became one of the museum’s most popular objects. It was shown with gold works in the 1953 Walters exhibition, 4000 Years of Modern Art, which was linked to the Museum of Modern Art exhibition, Timeless Aspects of Modern Art. It was part of a teaching portfolio of images chosen by curator René d’Harnoncourt, which were said to be related to each other on the basis of “affinity and resemblance” (fig. 6).20 The snake was also lent to a 1968 exhibition on ancient and modern Latin America at what was then the Isaac Delgado Museum, later the New Orleans Museum of Art, and was part of a 1971–72 exhibition, World of Wonder, at the Walters.21

From these rather unprepossessing beginnings, the Walters Art Museum’s ancient American collections and program were revitalized in the early 200s by significant gifts and loans, including a long-terms loan from the Stokes family of Nyack, New York; and, particularly, by a large gift from John Gilbert Bourne, given in 2009. The Walters engaged Matthew Robb (whose chapter on the St. Louis Art Museum is included in this volume) as a Visiting Assistant Curator between 2000 and 2003, and Khristaan Villela was a Consulting Curator of Arts of the Ancient Americas from 2010 to 2011. Conservator Julie Lauffenburger also played an important role in maintaining a focus on these works in the 2010s. I was hired as the first permanent Curator of the Art of the Americas in 2017, and dedicated galleries for the collection will open in 2025, finally enshrining in the twenty-first century a part of the collection that began to be formed in 1897.

The Baltimore Museum of Art

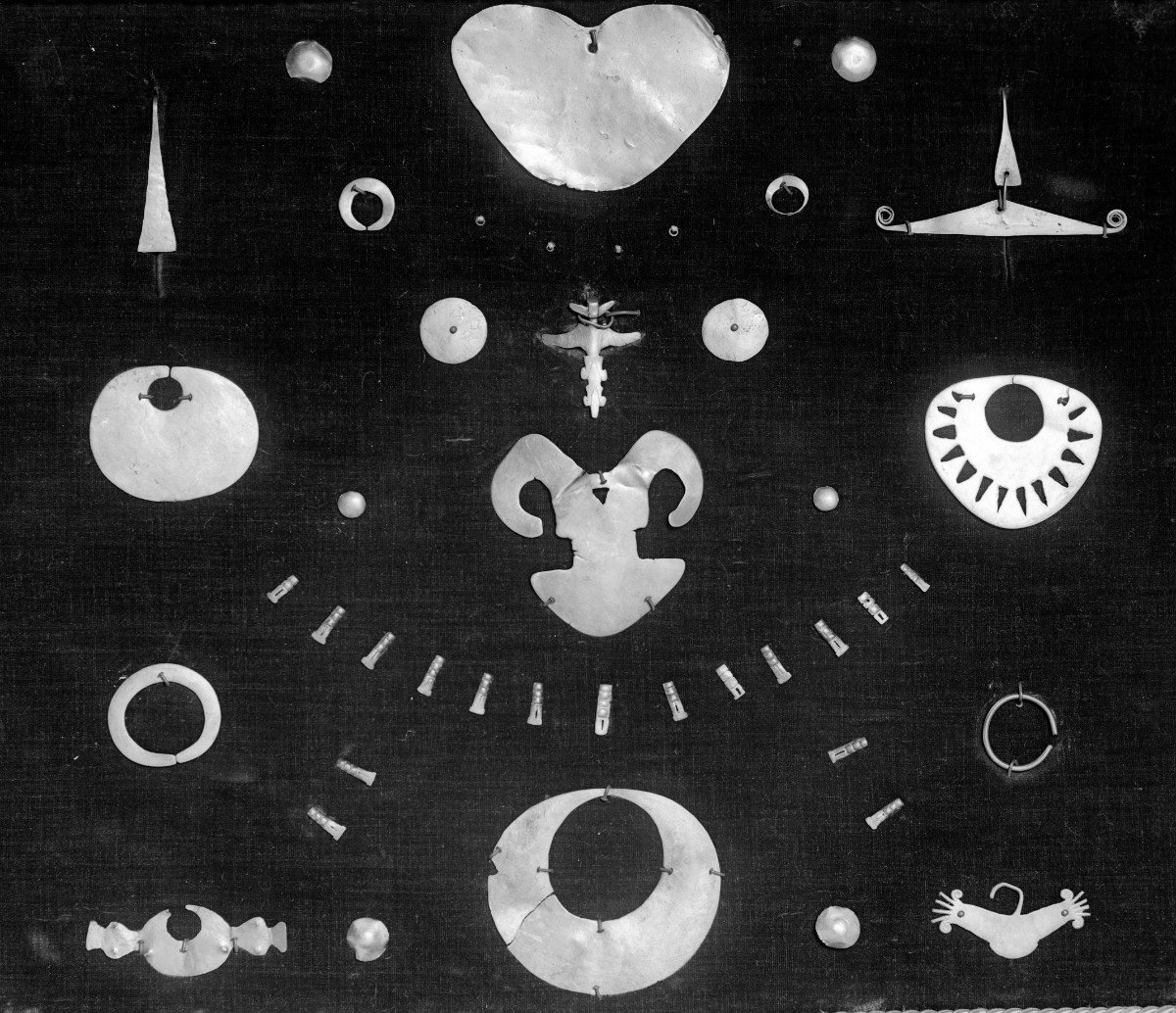

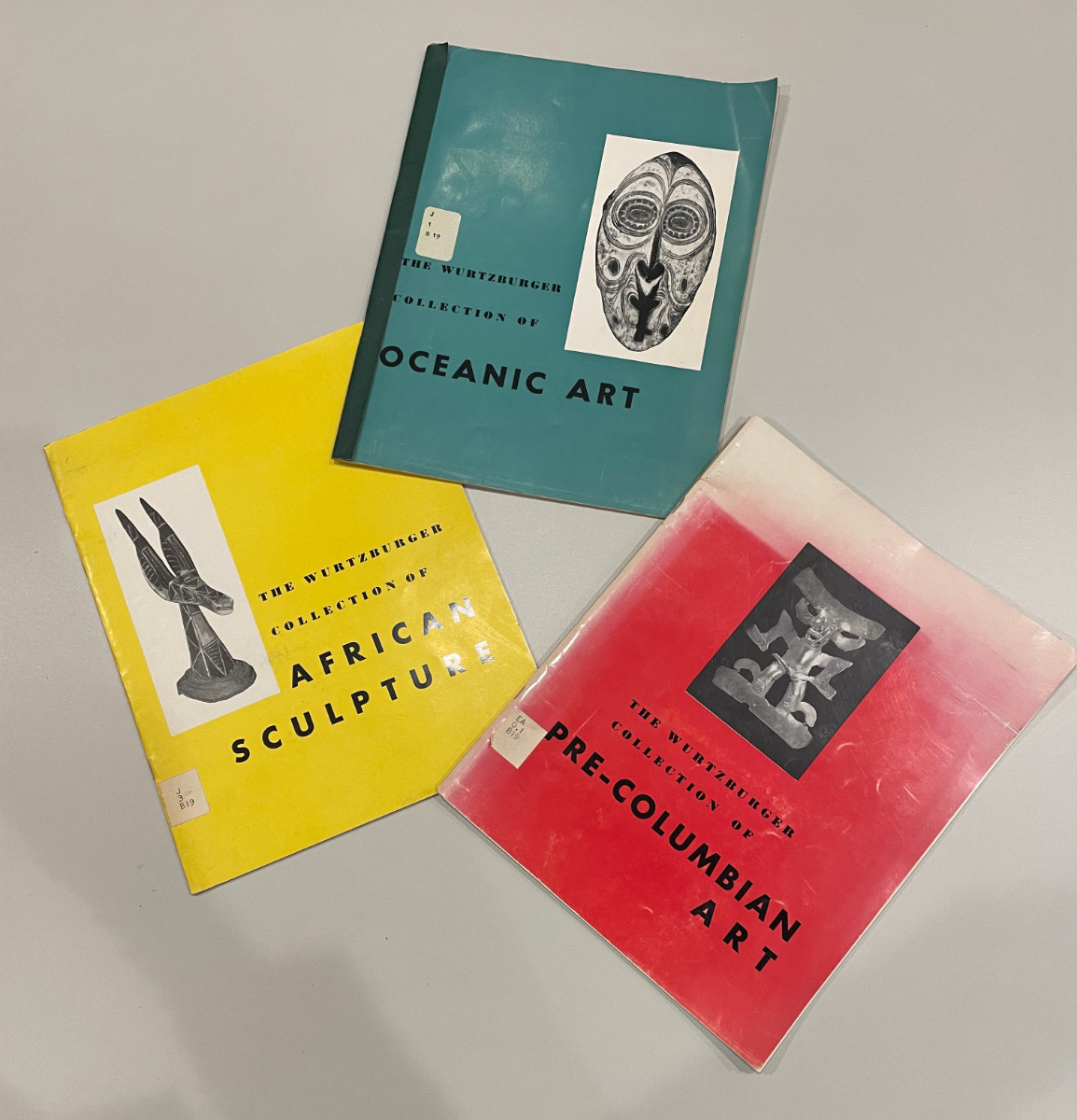

The Walters’s history stands in stark contrast to the situation at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), an institution in the same city with strikingly different conditions. The museum was formed by a range of individuals who came together to form a municipal museum. The driving force behind the collection was not a visionary dealer like Kunz, who created enthusiasm for a new collecting area, but the patrons themselves. While the director, Adelyn Breeskin (Acting Director 1942–47, Director 1947–62), and Chief Curator Gertrude Rosenthal, who worked at the BMA in various capacities from 1945 to 1969, were helpful, the main impetus for a major collection of ancient American art came from the donors themselves and was part of a larger push for a diverse “primitive” art collection at the museum, a common interest at midcentury. Real estate investor Alan Wurtzburger (1900–1963) and his wife, Janet (1908–1973), were the source of the BMA’s most significant collection of primitive art (figs. 7–9).

Before it began seriously collecting primitive art, the BMA presented several of the Pan-American exhibitions that were circulated by the Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) in the 1940s.22 It is interesting that these exhibitions were designed with broad audiences in mind—the 1944 Art in the Countries South of Us exhibition was held in the Junior Museum of the BMA and included toys, although the BMA News noted that this gallery, “though designed to familiarize children with our Latin American neighbors, will include material of general interest to adults as well.”23 The 1944 exhibition paled in comparison, though, to the 1950 Folk Arts of the South American Highlands exhibition, organized by the American Federation of Arts and shown at several museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago. It included about 160 works of ancient, colonial, and popular arts from Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru.24 From the images available, this was clearly a lush and costly show to mount, with mannequins in one corner and weavings on backstrap looms on another pedestal (fig. 10).

Additionally, a 1952 exhibition featured a bequest of approximately six hundred Native American works from Maryland resident Florence Reese Winslow, who later lived in the US Southwest. A Baltimore Sun article suggested that Frederic Douglas, curator of Native arts at the Denver Art Museum, and an important impetus in the founding of that ancient Americas collection, simply happened to be in in Baltimore when the bequest was announced and was immediately pressed into service cataloging and classifying the works in the gift. He is pictured in the Sun article surrounded by dozens of baskets.25

The Wurtzburgers’ gifts, then, bolstered and enhanced the BMA’s forays into exhibiting and collecting primitive art. As Frederick Lamp, former African art curator (1973–2004), described it: “In 1953, Adelyn Breeskin . . . and . . . Gertrude Rosenthal, were invited to lunch at Timberlane, the Baltimore home of Alan and Janet Wurtzburger. Their meeting was to result in the first significant formation of an African collection at the museum, and the basis of the collection today.” He continued, “At this luncheon [Alan] took Breeskin and Rosenthal out to a separate lodge on the grounds, where he showed them his new collection. They immediately decided to mount a loan exhibition, which was produced in 1954 with a catalogue introduced by Paul Wingert. A year later, the Wurtzburgers donated the entire collection to the museum and went on to begin other collections, first in Oceanic and then in pre-Columbian art, with the express purpose of forming a Wurtzburger Gallery of Primitive Arts at the BMA.”26 Lamp further recounted that the Wurtzburgers became interested in collecting primitive art when they were enlisted by their friend, the department store owner Stanley Marcus, to select African works for him to purchase when they were on a trip to South Africa in 1950.

While the couple didn’t find anything for the Marcus collection at that time, they were entranced by primitive art. They became friends with Douglas Newton, the curator of African art at the Museum of Primitive Art, who introduced them to experts, including Paul Wingert and Douglas Fraser, who were also influential in the formation of the collection of New York’s Museum of Primitive Art. Yet even with this guidance, according to former Native American arts curator at the BMA Katharine Fernstrom (1987–2002), the couple “restricted their collecting to purchases from other collectors and art dealers, rather than collecting ‘in the field,’ because they could obtain the best pieces from these sources.”27

After their gift of African art, by 1956 they had similarly donated a collection of more than two hundred Oceanic works. They also began purchasing Native American works: A 1956 profile asserted they were beginning their next collection in Russia seeking to “uncover choice works of Pacific Northwest Indian art collected by Russian seal hunters in Czarist days.”28 Yet, two years after the Oceanic gift, they then donated a collection of ancient American art, which was accorded its own catalog, with collection notes by Yale scholar George Kubler. In that same year, 1958, the Oceanic and African collections plus 105 works of ancient American art were among the approximately five hundred works exhibited in a new permanent primitive art gallery. At least one journalist asserted that “it is the new pre-Columbian section of the gallery that compels the greatest interest at the present moment. While neither so extensive as the Oceanic section, nor so rich in major objects as the African, it is of greater antiquity than either and entirely unfamiliar to art lovers.”29

Because of the breakneck speed of their collecting, the Wurtzburgers were learning as they went. Their lack of knowledge of and experience with much of the art, especially the pre-Columbian works, meant that they had to depend heavily on experts for guidance, and they bought from some of the most established dealers of the era. Some works may have come from Earl Stendahl on the West Coast, and one Zapotec effigy vessel (BMA 1960.30.26) still has a dealer’s sticker from the Galerie Charles Ratton of Paris affixed to it. The couple may have leaned toward works that had been published or promoted as particularly strong in quality. One small Mixtec or postclassic maskette of stone that ultimately ended up in Wurtzburger collection passed through the inventory of the influential Pierre Matisse Gallery of New York (fig. 11). An advertisement of 1939 shows it was offered for sale by Matisse in the year leading up to the monumental Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.30 Perhaps most importantly, like the Walters’ rattlesnake and deity figure, it was published by Pál Kelemen in his monumental Medieval American Art (1943), demonstrating yet again how tightly woven is the web of exhibitions, objects, publications, scholars, and dealers that connect our different institutions.31

The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Pierre Matisse was also instrumental in restarting the collecting of ancient American works by another pair of husband-and-wife collectors, Louise (1879–1953) and Walter (1878–1954) Arensberg. Walter was the son of an owner of a Pittsburgh steel crucible, and Louise was the daughter of a family that owned textile mills in Massachusetts. Once married, the couple lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, then moved to New York around 1911. They began collecting modern art from the Boston iteration of the Armory Show in 1913, and it quickly became a driving passion in their lives. While they were buying works by French modernists and actively participating in the creation of the New York Dada movement, they also bought at least three pre-Columbian works from the Mexican dealer Marius de Zayas during the 1910s while living in New York.32 But most of the almost five hundred ancient American works were acquired after they moved to Los Angeles in 1921. Walter Arensberg took his last trip to New York in 1937 and purchased a red stone coiled serpent (PMA 1950-134-215) from Matisse, as well as a number of works from the Brummer Gallery.33 The fact that Arensberg spent so much money on ancient American works was either spurred or inspired by the Los Angeles art dealer Earl Stendahl’s foray into this area; around this time, he began selling works to the Arensbergs almost weekly. I have previously written extensively about the genesis and formation of the Arensbergs’ collection of ancient American art.34 Here, I will focus on how their collection ultimately ended up in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA).

In 1940, the couple had agreed to donate their holdings to the University of California, Los Angeles, as long as the university’s museum created a new wing for them. When those plans fell through, the gift was pulled. A few years later, in 1945, Katherine Kuh and Daniel Cotton Rich of the Art Institute of Chicago visited. Kuh was a specialist in modern Latin America.35 But Kuh and Rich drastically reduced the number of pre-Columbian works that were to be shipped to Chicago for exhibition in juxtaposition with their modern works. This greatly irritated the Arensbergs, and they severed their agreement with Chicago by 1946. A few years later, Fiske Kimball, the director at the PMA, stepped in to seal the deal.36

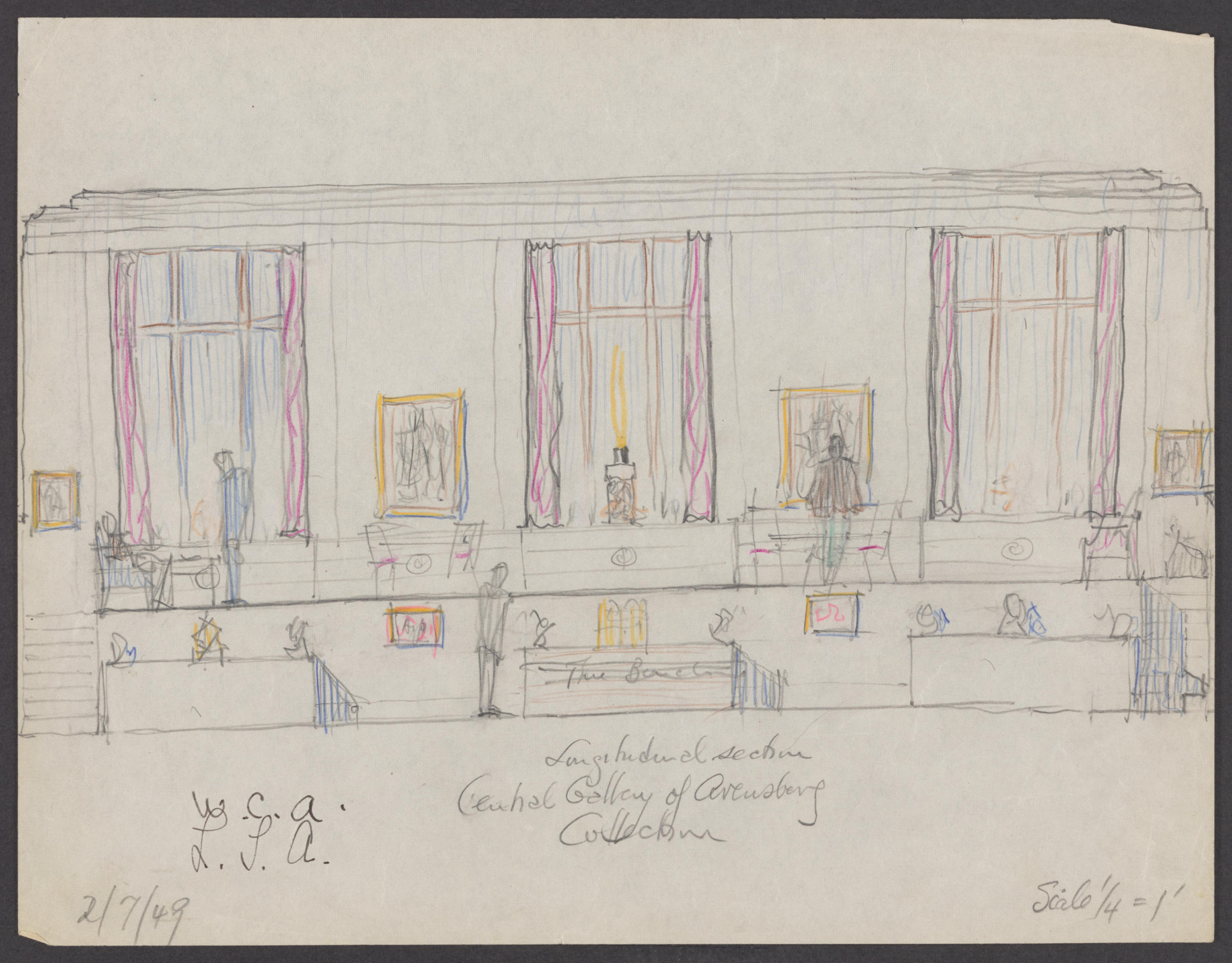

Kimball and his wife, Marie, made several visits to the Arensberg home and were in frequent contact with Sturgis Ingersoll, president of the PMA’s board, to strategize how to complete the gift (fig. 12). Marie Kimball and Louise Arensberg seem to have formed a bond, and perhaps by 1950, the Arensbergs, entering their seventies, were simply tired of “shopping” the institutions that courted them. Although the dissolution of the agreement with UCLA had been known for some time, when the collection was to be shipped to Philadelphia, it was apparently a surprise to the Los Angeles community, as a 1951 newspaper cartoon illustrates (fig. 13). The bespectacled East Coasters are shown carting off the small Teotihuacan goddess (PMA 1950-134-282) the couple owned. Reporter Kenneth Ross lamented the loss of the Arensbergs’ “two and a half million dollar collection of pre-Columbian and Modern art which every major city in America except LA asked for.”37

How, then, did Fiske Kimball succeed where Katharine Kuh and Daniel Catton Rich failed? This story is one of triumph after failure. Originally, the Arensbergs were quite insistent that they wanted the fruits of all their lives’ labors to stay together. Walter Arensberg, in particular, had three main passions in life: modern artworks, particularly conceptual ones made by Marcel Duchamp; ancient American sculpture, especially large stone works of the Mexica; and proving that Francis Bacon was the true author of the works commonly attributed to Shakespeare. During his early attempts to find a home for his art collection, Walter wanted all three parts of the triumvirate to stay together in a given location.

But by the time Kimball came to visit, Walter had been forced to relax his standards. Although there were some early discussions of merging the Francis Bacon Library, as his research center was called, with the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, these went nowhere, and the Bacon Library ultimately stayed on the campus of the Claremont Colleges near Los Angeles, while his art collections went east.38 As curator Matthew Affron has recently described in his account of how some of the world’s greatest modern art was gifted to the PMA between 1943 and 1950, landing the Arensberg collection was a success for Kimball only after a series of missteps. Kimball had organized large temporary exhibitions of the Chester Dale and Alfred Stieglitz collections, which ultimately went, in part or in whole, to other institutions, so by about 1950, he was highly motivated in his wooing of the couple.39

The PMA has had a complex construction history: A huge outer shell opened in 1928, but only fifteen interior permanent galleries were open to the public. Given that the Great Depression began shortly after the exterior was complete, it took decades to fully flesh out the permanent collections necessary to fill the museum. However, the empty spaces meant Kimball could be more nimble than other institutions in expanding the collections. In the case of the Arensbergs, Kimball used all his charm—and his drafting skills—to win their collection for his museum.

The PMA archive holds a small drawing of the central hall of the Arensberg galleries that Kimball promised the couple, with Brancusi’s Bench sketched out, next to what appear to be renderings of smaller Mexica deity figures and west Mexican ceramics (fig. 14). In correspondence with his board chair, Kimball revealed that his master stroke to seal the deal was producing detailed sketches, including this drawing, planning for “building your collection its dream house,” as Marie explained to Louise. Kimball telegraphed his board chair in excitement on February 7, 1949, when he succeeded in getting Louise and Walter to initial this drawing, which they did at bottom left—in essence formally accepting his proposal for their collection.40 Although it would take many more months to hammer out the final details of the agreement, Kimball and the PMA did not flinch from the challenges—or the shipping costs—of transporting a collection that included a large-scale corn goddess, a stone basin, and, particularly challenging, a greenstone Mexica calendar stone 33 inches across, nearly 20 inches high, and weighing some 1,380 pounds (PMA 1950-134-403).41

Kimball recognized the extraordinary power of these works, particularly the calendar stone, and centered them in the first exhibition of the Arensbergs’ collection, which included only their ancient American collection. It was installed in 1953 in a small special exhibition space, not yet the galleries that had been expressly designed for their collection (fig. 15).

While the spacing and lack of casework in this exhibition can be odd for twenty-first century tastes, Kimball and his designers were guiding a pre-Columbian installation that felt very streamlined and contemporary, even before the Arensbergs’ modern works were added. The tilted platform is echoed by zigzag shelves, which seem to riff on the Mesoamerican pyramidal form. Also, the stone works are displayed on pedestals, consciously marking them as art. I have not found information as to the paint scheme for this gallery, but color blocks would have set off the gray and brown of stone and ceramic objects, with physical blocks elevating them to different heights. Unfortunately, we do not have the Arensbergs’ thoughts on this exhibit, for they did not see it: Louise died in November 1953 and Walter in January 1954.

In 1954, once the Arensbergs’ modern works arrived at the museum, Kimball put the masterworks of the collection, both modern and pre-Columbian, into the central gallery that he had sketched out five years earlier (fig. 16). The Teotihuacan mural fragment, dominated by reds, must have been startling against the white walls. In this gallery, there was an equilibrium of ancient works, mostly stone, and the modern paintings and sculpture, all enclosed within the grid and arched spaces of the gallery.42 Kimball really had created a “dream home” for the Arensberg collection.43

Unfortunately, the PMA’s strategy of pairing ancient American works with European modern paintings and sculpture resonated with only the most cerebral visitors. Despite the PMA out maneuvering the Art Institute of Chicago for the Arensbergs’ collection, the PMA ultimately abandoned the original vison. The museum complied with its agreement to keep modern and ancient art displayed together for twenty-five years, but then it quietly removed much of the ancient American material from view. Perhaps this had to do with an informal agreement with the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn) that stipulated that the PMA would accept gifts of Asian art, while Penn would be home to African, Oceanic, and ancient American art.44 Whatever the reason, there has never been a dedicated curator who specializes in art of the ancient Americas. In recent years, major works from the PMA’s ancient American holdings have been on view, though, on loan to the Princeton Museum of Art and Penn.

Conclusion

The three museums discussed here all have drastically different origin stories: One founded by a single man heavily influenced by a single dealer to showcase craftsmanship and luxury materials; one formed in just two years by husband-and-wife donors looking to complete their collection to fill a gallery of “primitive” art; and one developed by a director willing to accession and ship thousands of pounds of stone to avoid losing out on a major collection of modern art. The legacies of these collections have also developed unevenly, but there is a growing sense that there is a new-found relevance and import to these collections of ancient American art. In the twenty-first century, the Latino populations in both Philadelphia and Baltimore, as well as the country as a whole, are growing quickly and are eager to see their history and heritage represented in US museums. As institutions seek to make heritage more accessible to descendant communities, there likely will be dedicated curators who have knowledge and expertise in ancient American art to engage these communities. And many such communities may be surprised that those collections do exist, for it was not only large institutions and those in largely Latino cities that amassed works of ancient American art. Smaller museums and those outside the major cities for art (New York, Chicago, and later the West Coast and Texas) were also essential to the network of dealers, donors, and directors that connected them to larger museums and larger trends in the history of collecting. Still by lending works, by keeping dealers afloat through (sometimes smaller) acquisitions, by offering venues for traveling Pan-American exhibitions, by making avant-garde installation design choices, and by making their collections available for key early publications, such as Kelemen’s Medieval American Art, these museums helped to create, expand, and make viable the web of ancient American art on public view at midcentury.

I am very grateful to Victoria Lyall for extending the invitation to work on this symposium and volume with her, and for her patience as I juggled too many activities. I am grateful as well to all the symposium participants for expanding my knowledge of the history of this field. For their assistance in various ways, thanks are also due to Matthew Affron, Lisa Anderson-Zhu, Kendra Brewer, Anna Clarkson, Elena Dammon, Sarah Dansberger, Angie Elliott, Carlee Forbes, Patricia Lagarde, Julie Lauffenburger, Earl Martin, Payton Phillips-Quintanilla, Ani Proser, Rona Razon, Kristen Regina, Edgar Reyes, Ana Salas, Ariel Tabritha, Michael Taylor, Kevin Tervala, René Treviño, Khristaan Villela, and Brynn White. This volume represents my thanks to my advisors, Diana Fane, James Oles, and Esther Pasztory.

Notes

-

Throughout this entire section, I am indebted to the research of former Bard Graduate intern Alice Winkler, whose article, “‘A Triumph of Detail’: George F. Kunz and the Promotion of American Gemstones and Design at the Walters Art Museum from 1876–1932” (forthcoming from the Journal of the Walters Art Museum), was extremely helpful for understanding Kunz’s marketing of ancient gold. He has been profiled in a number of articles and on websites as being a ground-breaking gemologist and not in his role art from the ancient Americas. ↩︎

-

For more on the Kunz axe, see “Kunz Axe,” American Museum of Natural History, accessed October 21, 2024, https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/permanent/mexico-central-america/kunz-axe; and “Kunze [sic] Axe,” Blackburn Art History, November 7 2018, https://blackburnarthistory.blogspot.com/2018/11/kunze-axe.html. ↩︎

-

Much of this information comes from a series of interviews in 1927 and 1928 that Kunz gave to The Saturday Evening Post, which are reprinted at Pala International, accessed October 31, 2024, https://www.palagems.com/kunz-reminiscences1. ↩︎

-

More information about the Walters family and their collecting activities can be found in William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters: The Reticent Collectors (Johns Hopkins University Press, in association with the Walters Art Gallery, 1999). ↩︎

-

The Walters’s vase (57.1055) and nautical ring (57.1123) are known to have been purchased at that time. Kunz and Walters could have also admired the replicas of ancient American temples shown at the fair. See Sven Schuster, “The World’s Fairs as Spaces of Global Knowledge: Latin American Archaeology and Anthropology in the Age of Exhibitions,” Journal of Global History 13, no. 1 (2018): 69–93. ↩︎

-

See Johnston, William and Henry Walters, 212–17; Mitch Noda, “George F. Kunz and Tiffany and Co.,” Meteorite Times Magazine, January 1, 2024, https://www.meteorite-times.com/george-f-kunz-and-tiffany-and-co/. ↩︎

-

Many, but not all, of these objects (accession numbers 57.262–57.352 and others) can be viewed in the Walters Art Museum’s online collection, accessed December 6, 2024, https://art.thewalters.org/search/?q=tiffany+%26+co.&era-to=bce&era-from=bce&category[]=AME. ↩︎

-

George F. Kunz, “Gold Ornaments from United States of Colombia,” The American Antiquarian 9 (September 1887): 267–80. ↩︎

-

Invoice, October 1, 1897, Walters Correspondence with Tiffany & Co., Walters Art Museum Library and Archives. ↩︎

-

A journal entry dated December 14, 1910, states that two jadeites and sixty-seven gold ornaments were received. Anderson Journal records, vol. 1, p. 40, Walters Art Museum Library and Archives. The Anderson Journal is named after James C. Anderson, superintendent of Henry Walters’s Baltimore art gallery and collections. The journal has two volumes that encompass the years 1908–32. For more on this source, see Elissa O’Loughlin, “Our Mr. Anderson,” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 70–71 (2012–2013): 137–42. ↩︎

-

George Kunz to Henry Walters, December 29, 1910, Walters Correspondence with Tiffany & Co., Walters Art Museum Library and Archives. ↩︎

-

Anderson Journal Records, vol. 1, p. 41, entry dated January 11, 1911. ↩︎

-

Karen Holmberg did attempt to trace different works sourced from Highland Chiriquí in the mid-nineteenth century but was not as interested in Tiffany’s presumptive role in marketing some of those works. See Karen Holmberg and Internet Archaeology, “The Archaeology of Highland Chiriqui, Panama—Documents, Images, and Datasets,” The Digital Archaeological Record, accessed October 31, 2024, https://core.tdar.org/project/4243/the-archaeology-of-highland-chiriqui-panama-documents-images-and-datasets. ↩︎

-

“Kelekian Purchase Book for 1911,” n.p., last two pages, Walters Art Museum Library and Archives. ↩︎

-

Johnston, William and Henry Walters, 190. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 335. ↩︎

-

Joanne Pillsbury, “Recovering the Missing Chapters,” in Making the Met, 1870–2020, ed. Andrea Bayer and Laura D. Corey (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2020), 209–15. ↩︎

-

Marie-France Fauvet-Berthelot and Leonardo López-Luján, “Édouard Pingret, un coleccionista europeo de mediados del siglo XIX,” Arqueología Mexicana, no. 114 (March–April 2012): 66–73. ↩︎

-

See Pál Kelemen, Medieval American Art, 2 vols. (Macmillan Company, 1943), vol. 1, 110, 112; vol. 2, plates 60a and 62b. ↩︎

-

René d’Harnoncourt, Teaching Portfolio No. 3: Modern Art Old and New (Museum of Modern Art, 1950), n.p. ↩︎

-

The Art of Ancient and Modern Latin America: Selections from Public and Private Collections in the United States (Isaac Delgado Museum of Art, 1968), cat. no. 35; Walters Art Gallery, World of Wonder: 1971–1972 (Walters Art Gallery, 1971), cat. no. 322. ↩︎

-

The Walters, as a former private collection, does not seem to have exhibited these same kinds of shows. ↩︎

-

Baltimore Museum of Art News, January 1994, 5. Quoted in description for Art in the Countries South of Us, BMA Building and Exhibition Lantern Slides, Archives and Manuscripts Collection, The Baltimore Museum of Art, accessed October 31, 2024, https://cdm16075.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15264coll5/id/59/rec/1. ↩︎

-

See “Gallery, Folk Arts of the South American Highlands exhibition,” Exhibitions Photographs Collection, Archives and Manuscripts Collection, The Baltimore Museum of Art, accessed October 31, 2023, https://cdm16075.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15264coll7/id/597/rec/2. ↩︎

-

“America’s Native Art,” The Sun (Baltimore), December 7, 1952, Mg16. ↩︎

-

Frederick Lamp, “African Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art,” African Arts 17 (November 1983): 38. ↩︎

-

Katharine W. Fernstrom, “The Alan Wurtzburger Oceanic Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art,” Pacific Arts, nos. 15/16 (July 1997): 89. ↩︎

-

“Oceanic Art: Masks of Beauty,” Time 67, no. 9 (February 27, 1956): 82. ↩︎

-

Kenneth B. Sawyer, “Art Notes: The Wurtzburger Collection,” The Sun (Baltimore), March 16, 1958, A23. ↩︎

-

Advertisement in Parnassus: A Publication of the College Art Association 11, no. 4 (1939): 2. On the importance of the Pierre Matisse gallery in marketing ancient American art at this time, see Megan O’Neil “The Changing Geographies of the Mesoamerican Antiquities Market circa 1940: Pierre Matisse and Earl Stendahl,” in Collecting Mesoamerican Art Before 1940: A New World of Latin American Antiquities, ed. Andrew Turner and Megan O’Neil (Getty Research Institute, 2024), 299–324. ↩︎

-

Kelemen, Medieval American Art, vol. 1, 301–02; vol. 2, pl. 247a. ↩︎

-

For more on the Arensbergs’ collecting activities, see Ellen Hoobler, “Smoothing the Path for Rough Stones: The Changing Role of Pre-Columbian Art in the Arensberg Collection,” in Mark Nelson, William H. Sherman, and Ellen Hoobler, Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L. A. (Getty Research Institute, 2020), 342–98. And on specific works sold by De Zayas, see ibid., 357–59. ↩︎

-

Invoice from Pierre Matisse to Walter Arensberg, May 14, 1937, Financial Records, Art collection, Arensberg Archives, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library & Archives, accessed October 31, 2024, https://www.duchamparchives.org/pma/archive/component/WLA_B028_F022_001/. ↩︎

-

Hoobler, “Smoothing the Path for Rough Stones.” ↩︎

-

See Elizabeth Pope’s essay in this volume and Mark Nelson and William H. Sherman, “The King and Queen Surrounded: The Arensberg Collection in Context,” in Nelson, Sherman, and Hoobler, Hollywood Arensberg, 58–59. ↩︎

-

Hoobler, “Smoothing the Path for Rough Stones,” 384. ↩︎

-

Kenneth Ross, “L. A. Lays Golden Egg, But Philadelphia Takes It Back Home to Hatch,” LA Daily News, January 20, 1951, in Arensberg gift, Clippings, Arensberg Archives, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library & Archives, accessed October 31, 2024, https://www.duchamparchives.org/pma/archive/component/WLA_B041_F039_012/. ↩︎

-

“Collection Overview, Description,” Bacon (Francis) Library Archive, Online Archive of California, accessed October 31, 2024, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cj8g5h/. ↩︎

-

Matthew Affron, “Introduction: How Modern Art Came to the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” in Le Avanguardie: capolavori del Philadelphia Museum of Art, ed. Matthew Affron (Skira, 2023), 13–24. English translation provided by the author. ↩︎

-

George and Mary Roberts, Triumph on Fairmount: Fiske Kimball and the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Lippincott, 1959), 254–66, 267–76. ↩︎

-

George Kubler, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection: Pre-Columbian Sculpture (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1954), pl. 51. ↩︎

-

It is interesting that there seem to have been a cluster of exhibitions around the early 1950s that juxtaposed ancient and modern works, from this Arensberg gallery to the shows at MoMA, the BMA, and the Walters, mentioned above, in connection with the Walters’ rattlesnake. ↩︎

-

Kimball also agreed to publish a catalog dedicated to the ancient American works only, which was authored by noted scholar George Kubler, who also wrote the Wurtzburger catalog. ↩︎

-

Matthew Affron, personal communication, 2023. ↩︎