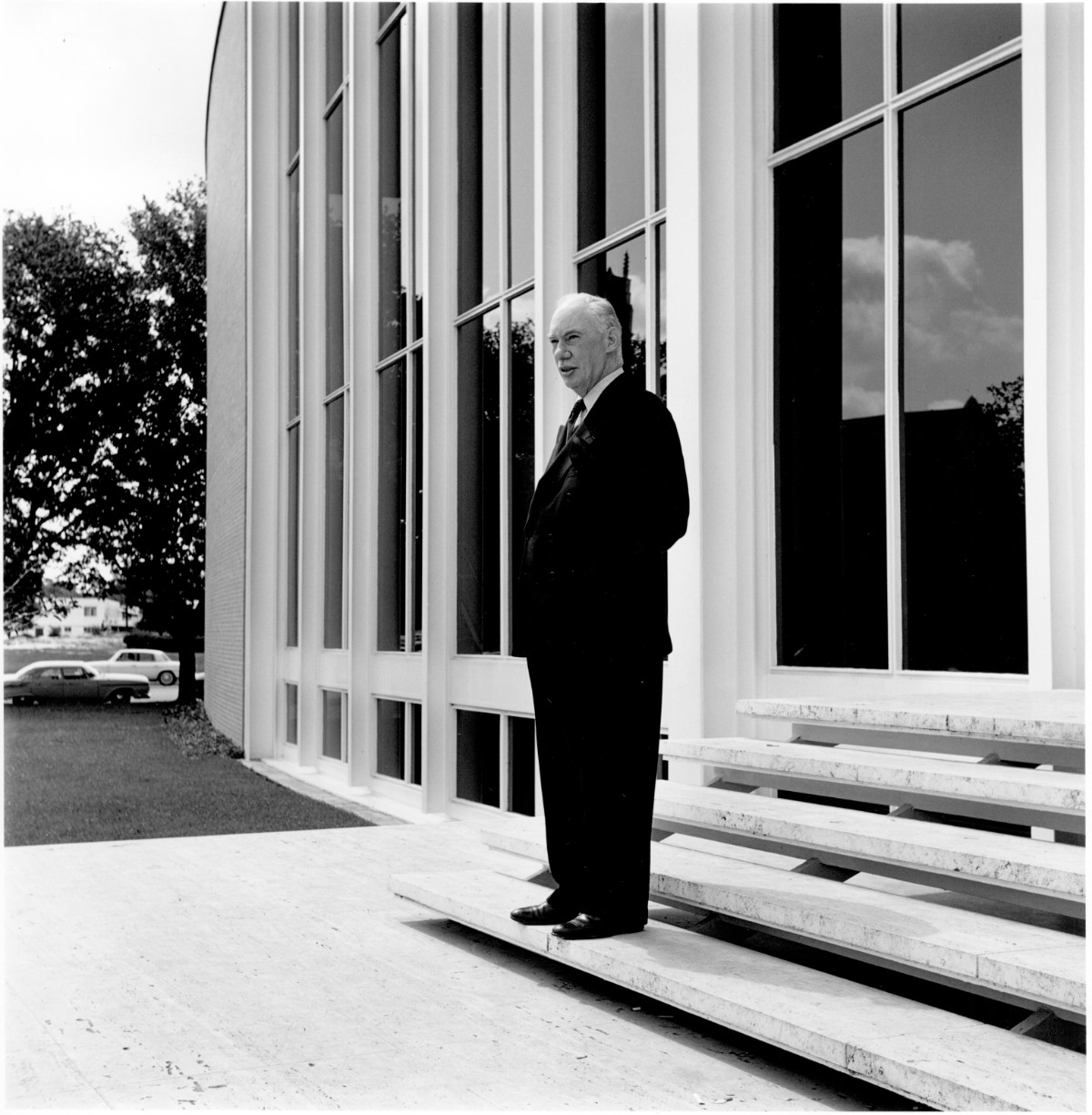

Although what would become the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), was established early in the twentieth century and found a permanent home in a neoclassical building by 1924, the MFAH was not early to the collecting or display of ancient American art. The museum’s initial relationship with that art began in earnest in the early 1960s, under the guidance of the recently appointed director of the museum, James Johnson Sweeney (1900–1986; fig. 1). Although central to the creation of an ancient American collection, Sweeney was not a scholar of the ancient Americas but a seasoned curator of modern art who had amassed a significant reputation in that area. Well before his arrival in Houston, Sweeney was committed to a view of non-Western art that highlighted that art’s utility to the contemporary project of constructing a modernist visual vocabulary. The initial impulse to collect and exhibit seriously in this area was shaped to some extent by Sweeney’s modernist commitments, certainly, but it was also as a way to garner national attention for the museum as the decade of the 1960s opened and Sweeney arrived from New York. These institutional goals drove the initial collecting of ancient American art as much or more than any scholarly concerns such as wide coverage of ancient American regional traditions or building deep collections in specific areas.

Before Sweeney: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1961

Before 1961 and Sweeney’s arrival as director, the MFAH’s ancient American collections consisted of a donation of one west Mexican ceramic sculpture given by John (1904–1973) and Dominique (1908–1997) de Menil along with a number of small ceramic and stone figures from Mesoamerica. By the time Sweeney left the director position in 1967, the ancient American collection included several hundred objects, mostly from Mesoamerica, including a handful of what would be considered masterworks. The museum also held one major international exhibition of ancient American art, The Olmec Tradition, discussed below, as well as an extensive exhibition highlighting the growth in the permanent collection. Sweeney achieved this remarkable growth in ancient American art collecting and display without the aid of a curator in the area. The first curator of ancient American art at the MFAH wouldn’t arrive until twenty years later.

What gave Sweeney the cachet—if not the expertise—to transform the ancient American collections at the MFAH? James Johnson Sweeney was considered a major force in the New York art world for decades before his arrival in Houston. He had done extensive curatorial work at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in its early years, creating important exhibitions between 1935 and 1946. He was briefly the head of painting and sculpture at MoMA in 1945–46. More important for this context, however, was his long run as the director of the Guggenheim Museum, beginning in 1952 and ending in 1960, shortly before he took up the directorship of the MFAH. It was Sweeney who oversaw the construction of the Frank Lloyd Wright building for the Guggenheim, and he installed the first exhibitions in that new, idiosyncratic space. Soon after the Wright building opened in late 1959, it became clear that Sweeney was unhappy with the new space and other institutional constraints and would be leaving.1 Sensing an opening, important MFAH trustees John and Dominique de Menil, who moved in similar New York circles, invited Sweeney to consider the MFAH directorship. Sweeney would soon assent, although it took almost a year for him to put things in order and move to Houston, arriving only in 1961.

After a long director search that seemed to be going nowhere, the trustees were excited to have found someone of Sweeney’s stature. John de Menil later called Sweeney “one of the most famous museum directors, nationally and internationally.”2 He and other trustees felt that the MFAH was in the midst of significant change. The trustees were clearly in favor of a much larger role for the museum on the national stage. The search committee chair, S. I. Morris (1914–2006), framed Sweeney’s hire as an “energetic plan to establish Houston as a national center of the arts.”3 As the museum press release on Sweeney’s hiring stated: “[MFAH] should take its place as one of the significant museums of the United States and of the world.”4 Sweeney’s charge, reiterated in no uncertain terms in correspondence to the incoming director, was to put the MFAH in the national and even international media discourse. In sum, Sweeney was considered a cosmopolitan and a giant in the US art world at a time when the MFAH trustees, led by John de Menil, wanted to increase Houston’s notoriety in the larger art world.

While trustees saw Sweeney as a national figure in museum administration that would increase the museum’s visibility and prestige, Sweeney saw himself as much more than simply an effective museum director. He was also a tastemaker.5 Sweeney was first and always an advocate for what he considered the best, most advanced modern art—The New York Times described him as “the arbiter of Modern Art” in a profile they did on the eve of his move to Houston.6 He viewed the role of the museum as an elevating experience for the viewer and was loath to focus on more purely didactic opportunities with his exhibitions.7 The visual experience of the best modern art should be the central focus of the museum, in Sweeney’s view.8 Elevating taste, which was about developing discernment in the viewer, was more important to Sweeney than art-historical facts and sequences. Sweeney’s privileging of the cultivation of taste over more pedagogical concerns was the deciding factor in the split between the Guggenheim and Sweeney, with the Guggenheim wanting a more robust education program and Sweeney decidedly against such a development.9 Sweeney was also against the ideal of the encyclopedic museum, insofar as the optimal museum experience should consist of seeing “not more than 150 paintings” and institutions should be “as big as a bistro . . . and no bigger.”10 In sum, Sweeney’s ideal museum was focused on an elevated visual experience that moved the modernist discourse forward. Much of the activity around ancient American art collecting and display may be seen in this context.

A Maya Panel and The Olmec Tradition: The Emergence of Ancient American Art at the MFAH, 1962–63

In 1962, or within a year of settling in Houston, James Johnson Sweeney used his discretionary fund—a newly created fund that was a prerequisite for his coming to Houston—to acquire a Classic Maya stone panel (fig. 2). There was nothing remotely like this large and expertly carved low relief in the museum collection, but such an acquisition at this time was not unusual on a national level. The early 1960s saw other Classic Maya pieces of similar quality enter various US public collections, including Nelson Rockefeller’s Museum of Primitive Art and a comparable stone panel from the same region acquired by Dumbarton Oaks.11 In the context of the MFAH, the acquisition of the Classic Maya panel was the beginning for Sweeney’s activities in this area.

In the following year (1963), the museum mounted a major special exhibition focused on Olmec art entitled The Olmec Tradition. The show was one of the earliest museum exhibitions in the US or Europe to focus on this singular and fundamental Mesoamerican art tradition.12 Figure 3 shows the facade of Cullinan Hall during the run of that show, when an original Olmec colossal head (San Lorenzo Monument 2) stood immediately outside the new modernist hall. The interior of the hall was filled with Olmec stone sculpture, much of it borrowed from the Museo de Antropología in Xalapa, Mexico (fig. 4).

Focusing on one region of Mesoamerica in an exhibition was an unusual strategy for a US (or European) museum at this time. One reason for this approach might be Sweeney’s known preference for focused shows as opposed to sprawling blockbuster exhibits.13 There were important countervailing forces to the idea of focused exhibitions of ancient American art, however. Large museum exhibitions featuring Mesoamerican art in the US and Europe up to this point had insisted on stitching together a Mexican national tradition, as seen in MoMA’s foundational Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art in 1940. The nationalist story is not just a MoMA or even a US penchant: The MFAH archive reveals that, as late as March 1962, Mexican officials were requesting that Sweeney widen the scope of the show to include “other aspects of the development of Mexican art through the Colonial Independence and Modern periods of our country.”14 For these correspondents, the nationalist frame had not changed substantially from 1940 and the Twenty Centuries exhibition to the early 1960s. To search for a consistent nonnationalist message in recent ancient American exhibitions (those of the 1950s and early ’60s), one would have to look at smaller, market-driven touring exhibitions like those organized by Stendhal Galleries of Los Angeles.15

The blockbuster Masterworks of Mexican Art exhibition traveling in Europe in the years immediately preceding Sweeney’s The Olmec Tradition is a relevant case in point. This show used the same nationalist (Mexican) lens seen in the earlier MoMA exhibition to circumscribe the many ancient American cultures in a larger national narrative. Instead of exploring a specific Mesoamerican tradition in depth, the nationalist show surveyed all pre-Conquest traditions found on Mexican soil and then appended the post-Conquest traditions, creating an all-encompassing national art-historical narrative. An ultimate iteration of Masterworks of Ancient Mexican Art, in Los Angeles, also included an Olmec colossal head, San Lorenzo Monument 5, that garnered much attention in the press and with attendees in the same year as Sweeney’s exhibition (1963).16 Instead of an exclusive focus on Olmec monumentality and the primacy of Gulf Coast civilization as seen in Sweeney’s show, the head was framed in the LA version of Masterworks as a founding moment in a larger national narrative of Mexican art.

In 1964, the year after the Olmec exhibition, Sweeney again deployed his director’s discretionary funds to acquire important ancient American stone sculptures (MFAH 64.38-39). These pieces were related to the Maya panel bought two years earlier in general glyphic style, and it is very likely that all three came from the western Maya region, abutting the Gulf Coast and directly adjacent in space (but not in time) to the material displayed in the Olmec show.

In the following year, the art of the ancient Americas takes an important place in the museum’s permanent collection with the gift of approximately two hundred Mesoamerican objects. The donation of Mrs. Harry C. (Alice Nicholson) Hanszen (1900–1977) included the Teotihuacan tripod vase (fig. 5), a Classic Veracruz yoke (fig. 6), and a number of other important pieces. The Hanszen donation contained fine examples of ancient Gulf Coast art but was not limited to that region. With the Hanszen gift as a sort of culmination, it is no exaggeration to say that, after the first four years of Sweeney’s tenure, the ancient American collections of the MFAH had been completely transformed and that this transformation had been driven by the director’s collecting habits and exhibitions.

While the Hanszen collection included objects from across Mesoamerica, the most important initiatives involving ancient American activities during Sweeney’s directorship revolved around the Gulf Coast region of Mesoamerica. It is difficult not to see a strategy of collecting and exhibiting what were viewed at the time as the finest ancient Gulf Coast objects, given the location of Houston and its rising regional prominence. By 1961, the city of Houston was touted in the popular press as one of the Gulf Coast’s largest ports and was soon to be the largest city on the Gulf.17 Although the institutional logic of a Gulf Coast thrust is appealing, the archive and Sweeney’s public statements do not indicate that such a regional focus played an important role in his strategy in the early 1960s.

While there is little archival evidence of a Gulf Coast strategy, there is more evidence for a strong interest in the larger category of ancient American art by Sweeney and the museum. Sweeney left an alluring but somewhat vague set of public statements on why ancient American art was such a key part of his strategy to improve the profile of the museum. In The Olmec Tradition catalog, Sweeney stated that “because of the closeness of Mexico to Houston, their historical links, their present, close financial associations, as well as Houston’s considerable Mexican population” the museum should focus on the art of the region.18 The art critic Dore Ashton wrote in 1963 that Sweeney thought the pre-Columbian tradition of the Southwest ought to be highlighted in Texas (but leaves “Southwest” undefined).19 A prominent trustee even raised the possibility of the MFAH becoming an “inter-American” museum, quoting Sweeney in this, although little of substance seems to have come of this idea.20 The archive does little to clarify these statements on collecting and exhibiting ancient American art. To better understand Sweeney’s strategy, it may be helpful to see his ancient American strategies in the light of the larger transformations under way at the museum.

Factors at work in the MFAH’s shifting identity in the early 1960s include Sweeney’s sense of the future of museums and important exhibitions outlined above and the new architectural envelope that he was called to work on while in Houston (more on this below). Although these factors may be seen as largely extraneous to a knowledge of Mesoamerican art and its regional traditions, they are important to our story because they were of fundamental importance to many of the key actors.21 The incorporation of complex institutional histories into the emergence of ancient American collecting and display requires a larger frame of analysis, one that encompasses prestige competition among museums, contemporary tastes in display strategies, and art market considerations, among other variables. Scholars have long justified this larger frame for the study of early collecting and exhibition strategies in major institutions.22 Museum collections of ancient American art were (and are) often “situated as much in the nexus of the chaos and energy of cultural production as they are representative of rigidly controlled hierarchies of aesthetics and taste,” in the words of Matthew Robb, speaking of the construction of ancient American collections more generally.23 In this case, the ambition for a larger national profile for the MFAH as understood by the director and key trustees, none of whom were versed in the ancient American art-historical discourse, was crucial to the emergence of ancient American art collecting and display in Houston.

Cullinan Hall

The construction of Cullinan Hall, opened in 1958 and seen above in figures 3 and 4, gave trustees and other stakeholders the feeling that the museum was ready to take its place on the national stage. In relation to earlier construction, the Cullinan was a bold modernist move. The original museum building, finished by 1926, featured a stately neoclassical facade and traditional interiors for the time (fig. 7). An extension of the building in 1953 did little to change the basic architectural character of the museum. Just three years before Sweeney’s arrival, however, Mies van der Rohe’s Cullinan Hall had been added to the original building, adding a soaring interior space along with the modernist facade.

It is difficult to exaggerate the radical nature of Cullinan Hall’s architecture in Houston at this time. The hall was one extended volume of approximately 10,000 square feet. The ceiling was anchored by steel plate girders that were 5 feet deep and 82 feet long, fanning out to bridge a 30-foot-high interior ceiling. The north facade featured dramatic floor-to-ceiling windows, and a Venetian terrazzo floor effectively grounded the interior space.

Before Sweeney’s arrival, the critic Eleanor Munro, writing in 1959, in ArtNews, distilled the situation for any curator bold enough to step into the space: Cullinan was a “grey-glass walled cell of empty space set as a kind of haughty challenge by architects to the arts of painting and sculpture.”24 Sweeney was well aware of the architectural challenge before accepting the director position. On arriving in Houston, Sweeney himself wryly noted, “I have had a little experience with difficult buildings.” This was surely a reference to his recent time at the Guggenheim, overseeing the building and installation in Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic space, which Sweeney ended up detesting. Sweeney continued about Cullinan Hall: “I admire Mies and find his hall inviting by comparison.”25 Heroic modernist paintings would enliven the space, alongside the monumental non-Western works that also played well in the hall’s enormous confines. A photograph of the Recent Acquisitions show mounted around the time Sweeney was planning The Olmec Tradition shows the combination of heroic modernist painting (hung from the ceiling by wire!) conversing with recently acquired large-scale Oceanic and African works (fig. 8). Each sculpture was given its own substantial space in the van der Rohe interior. Text was minimized, and each monumental artwork was left to speak for itself.

This is the same basic museological approach seen in The Olmec Tradition (see figure 4). We will let the exhibition photograph guide us to an understanding of the basic characteristics of Sweeney’s display strategies: 1) The great plastic sculptural statements of the Olmec are placed on pedestals and plinths; 2) Each object is isolated from the rest and set away from the wall, enhancing the ability of the viewer to experience the works in all their sculptural fullness; 3) Sweeney used no wall text and kept label text to a minimum. The absence of text was, for Sweeney, a point of pride and a call to use one’s critical visual faculties to make sense of the show. Here, Sweeney reveals his program most clearly: Much like his African sculpture exhibition at MoMA almost three decades earlier (African Negro Art, 1935), Sweeney focused exclusively on the formal aspects of the non-Western sculpture and eschewed the cultural history surrounding the pieces in both his curatorial strategies and in the catalog that accompanied the exhibition.26 Almost thirty years earlier, each large piece was already put on a plinth and given a significant amount of space, and text was minimized. As MFAH curator Alison Greene has noted about Sweeney’s Cullinan installations, “Sweeney celebrated the vastness of the space” in his most important modernist exhibitions.27 The same celebration of monumental works in the vastness of Cullinan is no less evident in The Olmec Tradition. Looking at Sweeney’s program through the lens of earlier twentieth-century modernist discourse, we can make more sense of Sweeney’s idiosyncratic essay in the exhibition catalog as well, which also eschews any art historical analysis for a tale of the movement of the colossal head and its resurrection against the Cullinan facade—a monumental work worthy of the monumental architectural statement behind.28 Inside, Sweeney deployed the smaller but no less monumental Olmec stone sculptures in dialogue with the grand modernist confines of the hall’s interior, with few textual or other impediments to experiencing this visual dialogue. For Sweeney, the single soaring space of Cullinan Hall supported the most emancipatory and heroic modernist painting and sculpture—as well as monumental non-Western sculpture.

The architectural historian Stephen Fox has argued that the construction of Cullinan Hall was a bid for a younger generation of the Houston elite to imprint a new emancipatory modernism on the city.29 In Fox’s view of this architectural statement, Miesian modernism eschewed decoration for more transparent construction. It also traded concealed and closed spaces for vast open spaces. In short, the new generation offered a democratically accessible space compared to the exclusion and intimacy of many older museum spaces, including the earlier MFAH building. One can overplay these dichotomous juxtapositions, but there is little doubt that the architect and his Houston patrons felt that Cullinan’s new sense of space was a transformative move for Houston that the new cosmopolitan director was charged with enlivening.

Cullinan Hall had already hosted a museological coup not long before Sweeney’s arrival: the 1959 show of mainly African art entitled Totem Not Taboo. With an innovative display strategy by Jermayne MacAgy (1914–1964), the favored curator of John and Dominique de Menil, this show was the first to show the possibilities of non-Western sculpture in the space, less than a year after it was completed.30 Particularly prescient in relation to The Olmec Tradition was the use of stark white pedestals to display large-scale sculpture—in this case, largely African sculpture in wood. However, as Greene observed, “MacAgy subtly tamed the scale of Cullinan Hall” by creating paths and well-defined subareas, while Sweeney celebrated the vastness of the space and the monumental qualities of the art inside, as alluded to above.31

Indigenous American Art

In addition to the usefulness of monumental Olmec sculpture to Sweeney’s modernist project of enlivening Cullinan Hall, there were also considerations of cultural diplomacy at work in early 1960s Houston. Sweeney is clearest on his diplomatic motivations for collecting and exhibiting ancient American art in his contribution to The Olmec Tradition catalog. He begins with a list of elements that bind Houston with Mexico, as noted above. He then lays out a program of exhibitions that will follow: an exhibition of colonial-period objects followed by one on contemporary Mexican art. In his larger hypothetical program, then, Sweeney has returned to the traditional nationalist art- historical paradigm that regulated the exhibition of this material from 1940 onward. He was, however, unable to realize either of these exhibitions while in Houston.

After his programmatic statement on a series of Mexico-focused exhibitions, he turns to a dream of his: to show an Olmec colossal head, like the one he could have seen in the traveling Mexican art shows of the late 1950s in Europe, in relation to the modern facade of Cullinan Hall. Sweeney realized this dream with this exhibition, mixing monumental non-Western art and modern architecture. The rest of his catalog contribution focuses on the voyage of an Olmec head from southern Veracruz to Houston for the opening of the show.

Spectacle of the Colossal Head

In his catalog essay, Sweeney recounts the movement of the head to Houston from Veracruz as a colorful narrative, full of drama.32 Here, Sweeney would allow his long-cultivated literary instincts some play. He describes the letters of support from both the president and vice president of the United States as well as his own voyage into the south Veracruz jungle to inspect the colossal head (fig. 9). He includes his meetings with imminent Mexican archaeologists Alfonso Medellín Zenil and Eusebio Dávalos Hurtado and the subsequent construction of a road more than thirty kilometers long in the region of San Lorenzo for the extraction of the colossal head—a road that also provided robbers with an escape after stealing a key object from the San Lorenzo site museum, as Sweeney notes. Other adventures involved helicopter flights to remote villages as well as the heroic efforts needed to get the head to Coatzacoalcos and onto a ship bound for Houston. Sweeney and the trustees also arranged for the movement of the head from Veracruz to Houston to be filmed and made into a short feature. Photographs from the voyage of the head are featured in Sweeney’s catalog essay. In the catalog and on film, the movement of the head was treated as a heroic coup for the museum.

Sweeney’s Masculinity and Primitive Art

One may ask what a veteran modernist museum director was doing traipsing through the jungles of southern Veracruz and personally overseeing the movement of multi-ton ancient monuments. It would have been easier, one could reasonably argue, to simply ask the Mexican authorities to deliver the head to Houston. The spectacle of discovery in the jungle, however, suited Sweeney’s persona and pleased his MFAH supporters. By this point, Sweeney had spent a lifetime cultivating the trope of the muscular, tenacious modernist critic, from his days on the rugby pitch for Jesus College in the University of Cambridge to the description of the inhuman energy he was able to muster in pursuit of his curatorial and writing projects. The director-as-explorer fit this persona well, and the media had a field day with the journey. The attention certainly raised the profile of the museum, especially in Houston but elsewhere in the country as well, which as we have seen was an important goal for the director and trustees. It is indicative of the importance of this event in Sweeney’s life story that more than thirty years later The New York Times gave considerable column space to the travels of the colossal head and its importance to Sweeney’s public profile in his obituary.33

Sweeney’s cultivation of this persona may be seen as part of his critical rhetoric as well. The art historian Marcia Brennan has parsed Sweeney’s rhetoric for gendered values and found that for Sweeney, good modern art was robustly plastic and coded masculine, while weak modern art was “decorative” and coded feminine. This gendered coding continued in his approach to art outside the Euro-American tradition, where an appreciation for the right formal qualities—the robust three-dimensionality evident in the Olmec sculptural corpus—allowed modern artists access to the intensity of intuitions that they needed to realize advanced modern works.34 For Sweeney, then, these non-Western objects (including ancient American objects) were instrumentalized: They helped modernists develop appropriate and productive (male) plastic conceptions. His was a decidedly formalist approach to the emergence of ancient Mesoamerican art at the MFAH, as it had been for African art earlier at MoMA.

Emergence of Sweeney’s Interest in Mesoamerican Art History (1965)

Sweeney’s deeply formalist approach to curating The Olmec Tradition goes back to his MoMA African art show and his early and important narratives of modernist history. The largely formalist appreciation held for the early Mesoamerican acquisitions as well. There is no record of his sustained interest in the historical context of the Maya panels or other early acquisitions. This situation changes in 1965, with the donation of the Hanszen collection of more than two hundred Mesoamerican objects mentioned in the museum’s collecting chronology above. It is in 1965–66 that Sweeney began corresponding with Michael Coe on San Lorenzo Olmec and Gordon Ekholm and Tatiana Proskouriakoff on the meaning and provenience of the Palenque region panel (his first Mesoamerican purchase—see figure 2).35 Sweeney also commits to a more historical approach in his 1966 exhibition Pre-Columbian Art, which used a geographic organizational scheme based on traditional Mesoamerican cultural divisions and chronologies for the 160 pieces displayed, with a catalog essay by Ekholm.36

With the installation of the Hanszen collection exhibition, Sweeney declares in the catalog preface that Houston now stood as one of the premier sites for the appreciation of Mesoamerican, or as he liked to put it, ancient Mexican art, in the United States.37 The de Menils rewarded these efforts with the donation of a large stone Aztec figure (MFAH 66.8) during the same year as the Hanszen exhibition. Not long after this donation, it became clear that Sweeney and the trustees were no longer in accord as to the future of the MFAH, and Sweeney stepped down from the directorship in the following year.

Conclusion

The transformation of ancient American collecting and exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, under James Johnson Sweeney was swift and dramatic. The museum went from a place practically devoid of ancient American objects to one which had a wide collection of Mesoamerican objects, with a number of works of international significance. The museum also mounted one of the earliest focused investigations of Olmec art as a major sculptural tradition in its own right. It is likely that the impetus for this transformation was not driven solely or even mainly by the desire to develop excellent collections in this area but instead served institutional desires far beyond Mesoamerican art history. The focus on ancient American art, while new to Sweeney, was originally part of a larger plan of cultural diplomacy between Texas and Mexico. Furthermore, Sweeney saw the development of Mesoamerican collections and especially The Olmec Tradition as a way to highlight the grand exhibition space of Cullinan Hall and activate its exterior. The monumental stone Olmec sculptures worked very well in the hall, as Sweeney knew they would. The spectacular movement of San Lorenzo Monument 2 (the colossal head) through the jungles of southern Veracruz and the waters of the Gulf Coast to the front of Cullinan Hall’s glass and steel facade created a heroic narrative that served to boost the museum’s regional and national profile.

Studying the rise of pre-Columbian collecting and exhibition in Houston through James Johnson Sweeney’s tenure as the director at the MFAH is an exercise in placing ancient American art amid “the chaos and energy of cultural production” of a museum on the move in the early 1960s. The social lives of these ancient American objects may be seen to take on more breadth as they are allowed to circulate in other conversations, some well outside ancient American art history. Such narratives help illuminate the myriad aesthetic and social forces that ran through these conversations that eventually created the US collections discussed in this volume.

Notes

-

“A Museum Director Resigns,” The New York Times, July 22, 1960, p. 22. ↩︎

-

Marcia Brennan, “Seeing the Unseen: James Johnson Sweeney and the de Menils,” in A Modern Patronage: De Menil Gifts to American and European Museums, ed. Josef Helfenstein (Menil Collection and Yale University Press, 2007), 35n7. ↩︎

-

S. I. Morris, quoted in Toni Ramona Beauchamp, “James Johnson Sweeney and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: 1961–1967” (master’s thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1983), 88. ↩︎

-

S. I. Morris, “1961 Sweeney Hire Press Release Draft,” Director’s Records, James Johnson Sweeney, Box 14, Folder 21, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Archives Collection (MFAH Archives Collection). ↩︎

-

James Johnson Sweeney, “Tastemakers and Tastebreakers,” The Georgia Review 14, no. 1 (1960): 90–100. ↩︎

-

“Arbiter of Modern Art: James Johnson Sweeney,” The New York Times, October 22, 1959, p. 40. ↩︎

-

James Johnson Sweeney, “The Artist and the Museum in a Mass Society,” Daedalus 89, no. 2 (1960): 354–58, especially 356. ↩︎

-

James Johnson Sweeney, “Some Ideas on Exhibition Installation,” Curator: The Museum Journal 2, no. 2 (1959): 151. ↩︎

-

“A Museum Director Resigns,” The New York Times. ↩︎

-

James Johnson Sweeney, quoted in W. G. Rogers, “Art Shows ‘Too Big and Safe,’” The Sun (Baltimore), December 11, 1955, p. A26 ↩︎

-

See James A. Doyle, “The Odyssey of Piedras Negras Stela 5,” in The Market for Mesoamerica: Reflections on the Sale of Pre-Columbian Antiquities, ed. Cara G. Tremain et al. (University Press of Florida, 2019), 93. ↩︎

-

Luis M. Castañeda, “Doubling Time,” Grey Room, no. 51 (2013): 14–15. ↩︎

-

Beauchamp, “James Johnson Sweeney and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston,” 137. ↩︎

-

Miguel Guajardo to James Johnson Sweeney, March 28, 1962, Registrar’s Records, Exhibition Files March–June 1963, Box 25, Folder 9, MFAH Archives Collection. ↩︎

-

See Alfred Stendhal, Pre-Columbian Art: A Loan Exhibition of Objects Illustrating the Cultures of Middle American Civilizations Before Their Conquest by Cortez (Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, 1950) and the many iterations of this show, often with a similar title in different venues throughout the 1950s. For a larger context of these exhibitions, see Megan E. O’Neil and Mary E. Miller, “Stendahl Art Galleries in Europe: Expanding the Market for Pre-Hispanic Art at Mid-Century,” Journal for Art Market Studies 7, no. 1 (2023), https://www.fokum-jams.org/index.php/jams/article/view/143. ↩︎

-

Castañeda, “Doubling Time,” 12–39. ↩︎

-

Stanley Walker, “The Fabulous State of Texas,” National Geographic 119, no. 2 (1961): 149–95. ↩︎

-

Alfonso Medellín Zenil and James Johnson Sweeney, The Olmec Tradition (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1963), n.p., quote found at the beginning of the section “A Head from San Lorenzo.” ↩︎

-

Dore Ashton, “Sweeney Revisited,” Studio International 166, no. 845 (1963): 110–13. ↩︎

-

S. I. Morris, “Inter-American Museum,” August 22, 1962, Trustee Records; Trustee Committees 1959/60–1963/64, Box 02, Folder 51, MFAH Archives Collection. ↩︎

-

S. I. Morris, “1961 Sweeney Hire Press Release Draft,” January 4, 1961, Trustee Records; Trustee Committees 1959/60–1963/64, Box 2, Folder 41, MFAH Archives Collection. Sweeney in a quote related in this document gives wide latitude to possible collecting strategies for the MFAH: “It should not look for its acquisitions and đisplays merely to the United States and Europe, but also to the Orient and to the Americas south of the Rio Grande.” ↩︎

-

Holly Barnet-Sánchez, “The Necessity of Pre-Columbian Art in the United States: Appropriations and Transformations of Heritage, 1933–1945,” in Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past, ed. Elizabeth Hill Boone (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1993), 182. ↩︎

-

Matthew H. Robb, “Lords of the Underworld—and of Sipán: Comments on the University Museum and the Study of Ancient American Art and Archaeology,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 1, no. 1 (2019): 118. ↩︎

-

Eleanor Munro, quoted in Michael Grogan, “Texas Two Step: Ludwig Mies van Der Rohe’s Addition(s) to Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts,” Arris: The Journal of the Southeast Chapter of Architectural Historians 31 (2020): 106. ↩︎

-

Ann Holmes, “Now, Sweeney’s Slam on Houston,” Houston Chronicle, January 11, 1961. ↩︎

-

For exhibition installation images and other documentation, see “African Negro Art, Mar 18–May 19, 1935,” Museum of Modern Art, accessed September 11, 2024, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2937?. For Sweeney’s curatorial strategy, see James Johnson Sweeney, African Negro Art (Museum of Modern Art, 1935). ↩︎

-

Alison de Lima Greene, “Modernism in Houston,” Art Lies 41 (2003): 22. ↩︎

-

Zenil and Sweeney, The Olmec Tradition, n.p. ↩︎

-

Stephen Fox, “Cullinan Hall: A Window on Modern Houston,” Journal of Architectural Education 54, no. 3 (2001): 159. ↩︎

-

Lynn Herbert, “Seeing Was Believing: Installations of Jermayne MacAgy and James Johnson Sweeney,” Cite, no. 40 (1997–1998): 32, https://repository.rice.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/57a23361-dfac-4fbd-9311-2e97c7700281/content. ↩︎

-

Greene, “Modernism in Houston.” ↩︎

-

Zenil and Sweeney, The Olmec Tradition, n.p. ↩︎

-

Grace Glueck, “James Johnson Sweeney Dies; Art Critic and Museum Head,” The New York Times, April 15, 1986, p. B8. ↩︎

-

Marcia Brennan, “The Multiple Masculinities of Canonical Modernism: James Johnson Sweeney and Alfred H. Barr Jr. in the 1930s,” in Partisan Canons, ed. Anna Brzyski (Duke University Press, 2007), 190. ↩︎

-

For example, see Sweeney to Michael Coe, October 20, 1966, Director’s Records, James Johnson Sweeney, Box 4, Folder 19, MFAH Archives Collection. ↩︎

-

Gordon F. Ekholm, Pre-Columbian Art from Middle America: Gift of Mrs. Harry C. Hanszen (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1966). ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎