Comparatively few art museums are so fortunate as to be regarded as ministering in a real way to the requirement of their communities, and yet, under the conditions of modern life, it is only upon these terms that an art museum can, in the long run, justify its existence.—George Eggers, Denver Art Museum director (1921–26)

The Denver Art Museum (DAM) came into being decades after The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Art Institute of Chicago. First founded as the Denver Artists’ Club, it would become the Denver Artists Association in 1893, a scant seventeen years after the Colorado territory had become a state. A place to “cultivate a general interest and promotion of the arts,” the museum was powered by volunteers who imbued it with an independent spirit it retains today.1

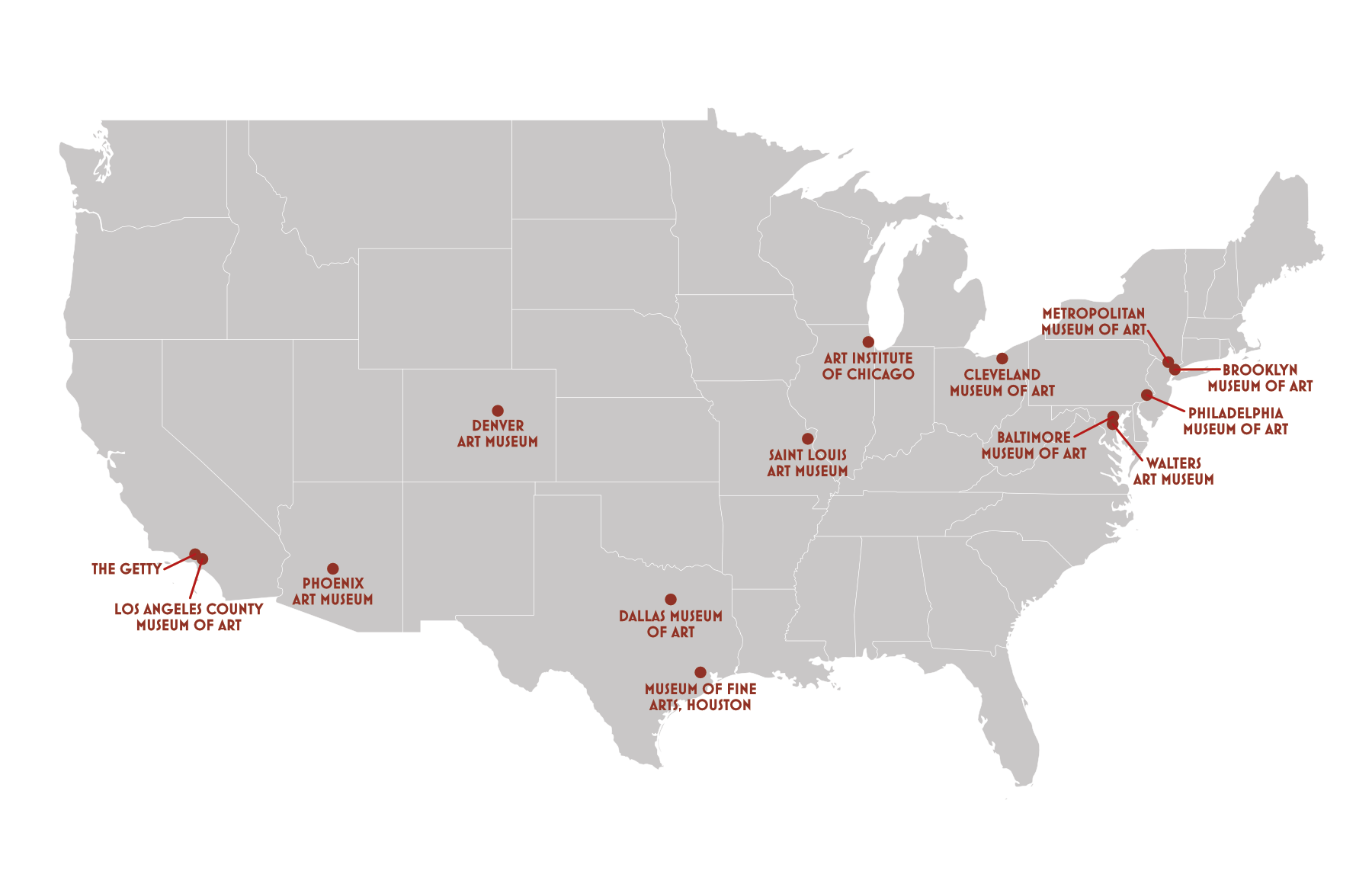

Denver’s location within the broader geography of the United States plays an outsize role in the institution’s identity and its approach to its collections, audiences, and patrons. Located at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, it is surrounded by a vast expanse of land: About eight hundred miles separate it from the next largest global art museum (fig. 1).2 The city sits spitting distance from the center of the country. Because of its geography, the DAM felt a responsibility beyond its immediate surroundings: “What the Metropolitan Museum is to New York, the Art Institute to Chicago, the Louvre to Paris, and the British Museum to London, the Denver Art Museum is to Denver and the whole Rocky Mountain region.”3 Today it stands as the largest encyclopedic art museum between Chicago and Los Angeles. Like the other institutions discussed in this volume, early directors, curators, and collectors played an essential role in assembling and shaping the ancient Americas collection. But I would also argue that the museum’s geographic location played an equally significant role. This essay is an exercise in retrieving and reconstructing an often invisible and forgotten history that I hope will remind us of the very human aspect of museums.

In 1968, then-director Otto Bach (1909–1990) formed the New World Department, which brought together existing Latin American and pre-Columbian material under one umbrella. A collection of southwestern santos donated by an early patron, Anne Evans, and the several hundred works of pre-Columbian objects were recategorized as “New World.” This designation, a phrase borrowed from the writings of European explorers, described the “discovery” of new lands, territories claimed for European empires. Its use was unique within American art museums; at the DAM, it would refer to the territory of the Americas south of the US-Mexico border. Today, the term reminds us of the five-hundred-year colonization and subjugation of American peoples and, rightfully, has been abandoned. The decision in 1968 to use the term to describe a disparate collection of objects united only by their shared geography, however, represented a groundbreaking perspective. It conceptually connected the makers of southwestern santos to the ancient artists of Mexico, Guatemala, and beyond. In fact, Bach’s foresight and those of subsequent curators is what distinguishes Denver’s holdings today: It stands as one of the most expansive and comprehensive collections of the Americas within the United States, capturing the history of the region from the beginning of agriculture to the formation of nineteenth-century republics.

Anne Evans, Frederic H. Douglas, and the Creation of a Regional Collection

Although the department came into being during the midcentury, the heyday of pre-Columbian art, its history begins much earlier. The youngest daughter of Colorado governor John Evans, Anne Evans (1871–1941) was born in London and educated between the mountainous landscape of Colorado and the rarified art collections of Europe and the American East Coast. She studied art at the New York Art Students League and summered at the Evanses’ Colorado ranch.4 Evans and her mother devoted themselves to developing Colorado’s cultural sphere, and she would ultimately play a pivotal role in the founding of the Denver Art Museum, serving as the executive secretary, interim director, and ongoing consultant. As the museum took shape, Evans herself began to collect southwestern santos and American Indian art, becoming one of its most ardent promoters. She encouraged the DAM to fund acquisitions, exhibitions, and finally, in 1925, to hire a full-time curator of American Indian art. Upon her death, she donated her entire collection of santos and bultos to the museum (fig. 2). This collection, which showcases the mastery of southwestern wood carvers and painters, draws on both Catholic and Native American imagery, reflecting the region’s and the artists’ own multicultural backgrounds. Through her efforts, Evans ensured the Denver Art Museum’s place as a groundbreaking institution that valued American Indian culture and history.5

It’s difficult to consider Anne’s identity as a collector and promoter of American Indian and southwestern art separate from her father’s legacy. Dr. John Evans, the second territorial governor of Colorado, appointed by Abraham Lincoln, was a physician and railroad titan who would play a hand in the founding of both Northwestern University and University of Denver; however, the Sand Creek Massacre would become his lasting legacy. On November 29, 1864, hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapahoe people were murdered by the US Army. Evans was out of the state on business, but as several studies have concluded, his lack of enforcing Indian treaties and habitual neglect of the Cheyenne and Arapahoe peoples contributed to this tragedy.6 His daughter’s efforts to uplift and validate the material culture and aesthetics of Native communities from this region and beyond resulted in the creation of three separate departments at the museum: Native Arts, Ancient Americas, and Latin American Art. One hundred and sixty years later, these collections continue to amplify the stories and voices of Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Frederic “Eric” Douglas (1897–1956), a native Coloradan, joined the museum in 1929 as curator of American Indian art. He would go on to serve the institution for three decades as curator and interim director until his death in 1956.7 Douglas was perhaps most well-known for his role in organizing Indian Art of the United States, the 1941 Museum of Modern Art exhibition he cocurated with René d’Harnoncourt, but his true contribution was the establishment of a singular curatorial perspective at the DAM that integrated Native American art into the museum’s fine art collection (fig. 3).8 Unlike contemporaries around the United States that categorized Indigenous art as “decorative,” Douglas advocated tirelessly for viewing these works on par with that of the great masterpieces of Europe and for the living artists who produced them as individuals possessing a rare skill and expertise.

His attitude and character are most clearly captured in his correspondence with the newly appointed director Otto Bach while Douglas was stationed overseas in 1944. Douglas vehemently objected to Bach’s application of the term “primitive” on two accounts. First, by applying the term to the Department of Indian Art, in Douglas’s opinion, Bach lumped the DAM with other museums that had similar departments. Douglas noted that among American art museums, only Denver had “postulated that the American Indian had arts worthy of serious esthetic consideration.”9 This objection captures Douglas’s zeal and dedication to the department he had almost single-handedly created and what today we may refer to as his legacy. To his credit, his second objection was: “The use of the word primitive has a connotation of condescension and snobbery both artistic and social. . . . It is a very poor thing to look down our noses however politely at the works of other than our own race, especially if that other is not what is laughingly called white. . . . It’s the wrong use of the word however you look at it and I’ll have no part of it.”10 In addition to clarifying Douglas’s position, this exchange also provides insight into the fraught relationship between the two men.

While Douglas’s extraordinary vision and open-mindedness resulted in the creation of a singular department, he largely ignored historical and contemporary Indigenous peoples living south of the US-Mexico border. Eleanor Roosevelt penned the foreword to Indian Art of the United States and pointedly referenced the interchange of goods and ideas north and south, perhaps a nod to her husband’s promotion of inter-American cooperation; however, Douglas’s correspondence clearly indicates that, in his mind, a bright line separated the two Americas, and he collected exclusively north of the US-Mexico border.11 But when the museum received several gifts of ancient American material, they were administered by the Native Arts department until 1968.

Otto Bach: Building a New World

Denver Post journalist Bill Hornby wrote an appreciation of Otto Bach after his passing in 1990 and noted: “The man who really put our Art Museum on the world cultural map was Dr. Otto Karl Bach, its director and guiding spirit from 1944–1974. Whether it was in acquiring renowned collections, buying land for expansion, insisting on developing the museum education program for all the people or instilling the tradition that Denver was going to have a world class art collection, Otto and Cile Bach were the driving spirits of the modern Denver Art Museum.”12 Bach’s thirty-year tenure would transform the museum from a local, provincial institution to one of national renown. Moreover, it would be through Bach and his ministrations that the ancient Americas collection would take shape.

Bach moved to Denver with his wife, Cile, and their young son from Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1944. In a letter to Douglas introducing himself, Bach explained that his training was in European art, but he had served as a museum administrator for twelve years, first in Milwaukee and later in Grand Rapids.13 His goal, clearly laid out in 1944, was to build a new permanent home for the DAM, which he would achieve in 1971 with the opening of the Gio Ponti–designed building.14

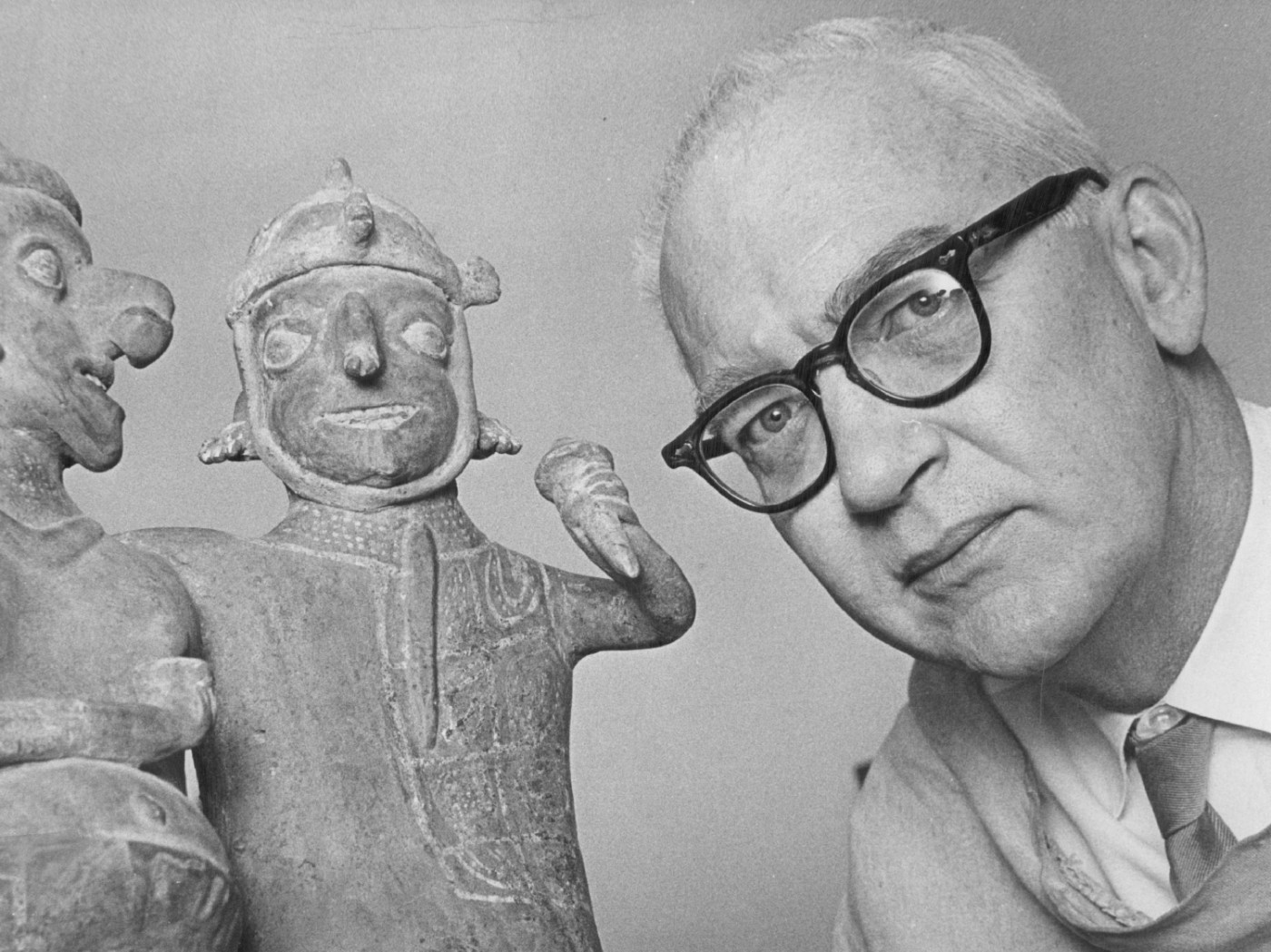

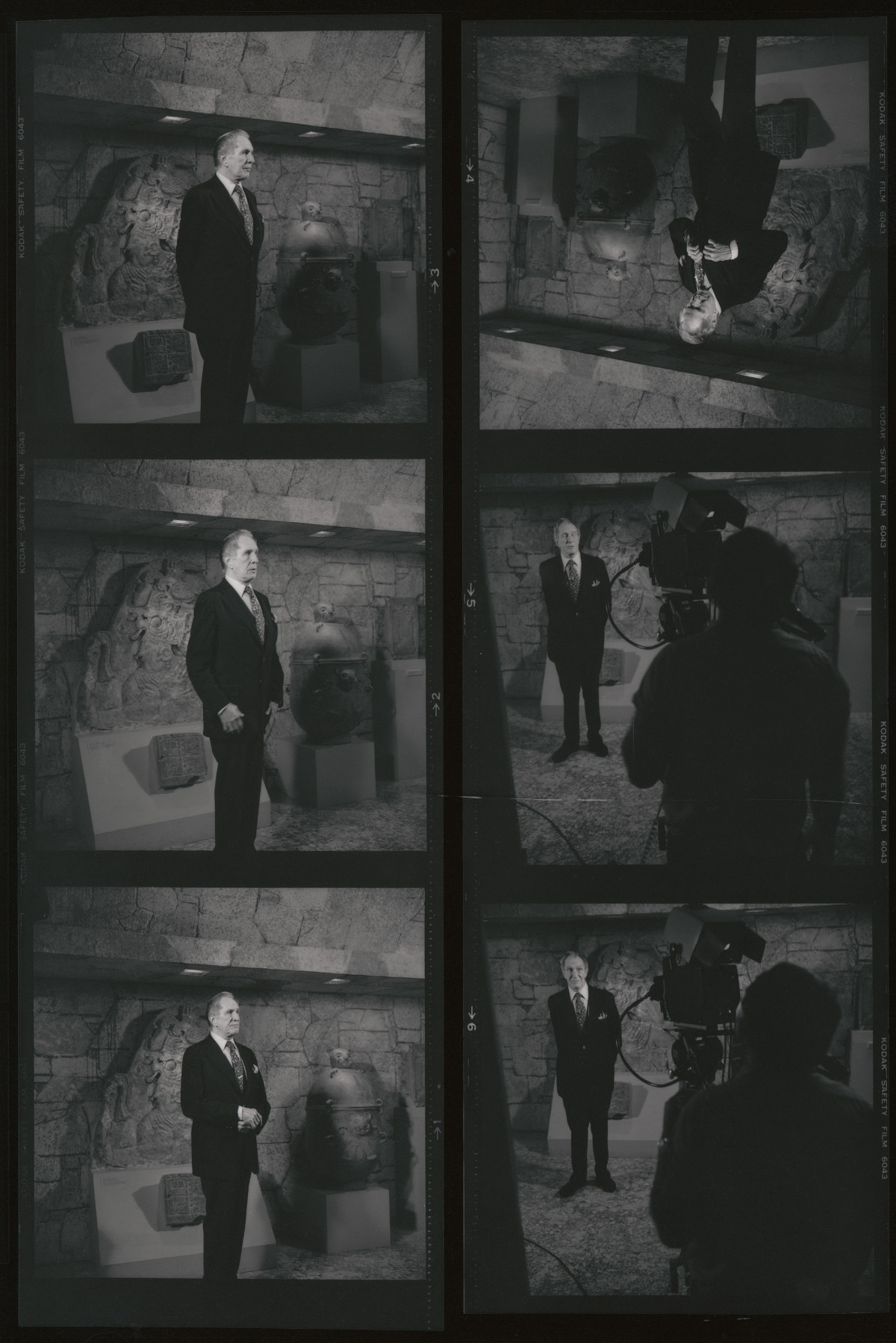

Somewhere along the way, Bach developed a love for art of the ancient Americas (fig. 4). From his first acquisition in 1951 until 1974, when he retired, Bach almost single-handedly built the ancient Americas collection that came to number over one thousand pieces. A museum built on volunteerism, the DAM remained people rich and dollar poor. As a result, Bach would cajole dealers and trade, exchange, buy on credit, and deaccession objects to get the works he wanted.

In 1956, three months after Douglas’s passing, Dr. Karl Arndt, board president, asked Bach to review the collections in the Native Arts Department with recommendations for culling, keeping, exchanging, and lending.15 Bach explained that the American Indian collection consisted of thousands of objects with scores of duplications—some identical: “Mr. Conn and Mr. Bach believe that each category of material should be checked carefully, in small units, with an eye to weeding out duplicates and sub-standard material and replacing it with objects which are of better quality or more uniqueness, or filling in gaps in pre-Columbian, Mexican pre-historic, Mound Builders or other areas which are lacking in representative material.”16 As Lewis Story, DAM’s assistant director at the time, observed, Bach’s decision to further develop collections of African, Oceanic, and pre-Columbian holdings allowed him to serve “a multicultural constituency more effectively.”17 Over the next several years, Bach would work to drum up support via the museum’s various affiliated committees specifically to acquire ancient Americas objects. Here, in this image from a 1959 board report, Bach proudly stands with the chairwoman of the Women’s Committee, who contributed funds to acquire the ceramic head (fig. 5).

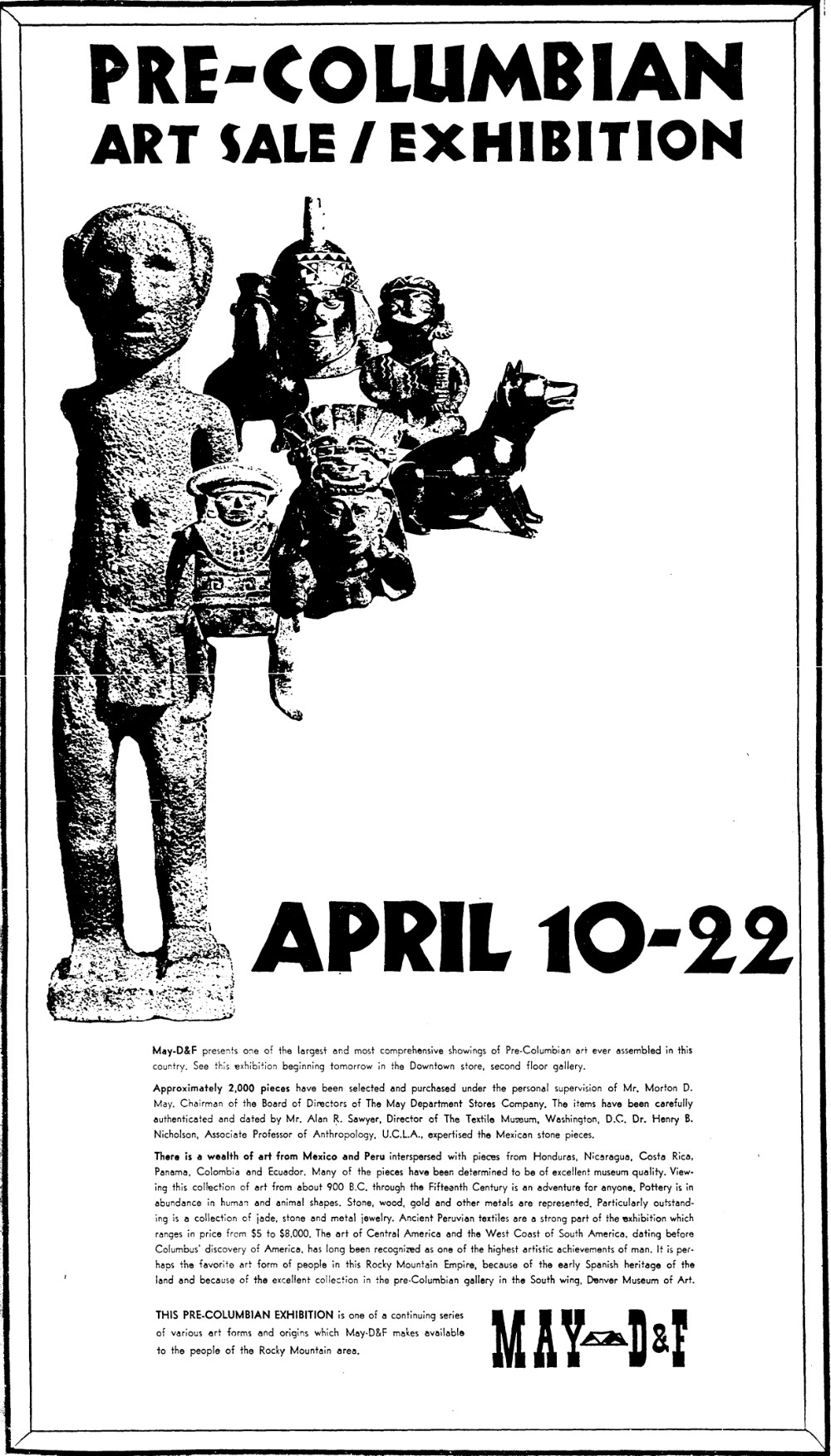

As other authors in this volume note, America at midcentury was captivated by the ancient Americas (see essays by Rosoff, Koontz, and Robb). A steady stream of exhibitions traveled around the country, or were organized locally, to showcase the wonders of “lost” or “mysterious” civilizations.18 Beginning in 1950, Bach worked to bring many of these shows to Denver. Exhibitions featuring Middle American gold, ancient Peruvian artwork, and “Pre-Columbian and Contemporary Art” began appearing in the Schleier Memorial Gallery with some frequency between 1950 and 1960 (fig. 6).19 During the run of the exhibitions, Bach befriended the dealers and collectors who lent work to the shows, ultimately securing one or two pieces for the DAM’s growing collection. The museum’s annual reports began featuring names such as Julius Carlebach and Earl Stendahl.20 Additionally, Bach, ever the promoter, penned short articles for The Denver Post, celebrating the acquisition of pre-Columbian objects at the museum.21 While Bach acquired these works through trades and exchanges, these acquisitions provoked the ire of the board.22 These transactions became so prevalent that, during one contentious board meeting in 1967, a trustee lamented the number of times he went to the gallery and realized a beloved piece was missing.23 He called for greater transparency for trades and exchanges. Unfortunately, his words were not heeded.

Bach continued growing the collection of art from the Americas incrementally. By 1967, there were 153 pre-Columbian works in the DAM’s collection.24 In 1968, he decided to join the pre-Columbian objects from Mexico and Central and South America with Anne Evans’s southwestern santos collection to officially create the New World Department. With this new arrangement, the story of the art of the Americas could now be seen sequentially, connecting the ancient with the more recent past.25

Forming the Collection: Robert Stroessner, Morton May, and the Mayers

Bach hired Robert Stroessner (1942–1991), who received a degree in interior design from the University of Denver, as the inaugural New World curator (fig. 7). An assistant curator in Native Arts under Norman Feder, Stroessner had been Bach’s student and protégé and, like Bach, understood the history of the Americas as part of a single continuum.26 He took pride in Denver’s regional approach, writing to donors that the museum’s decision to include both ancient and colonial art from Latin America under the same umbrella was unusual. In a 1974 letter to the new director, Tom Maytham, Stroessner underscored the New World Department’s unique approach: “We have tried to systematically select representative examples to form a chain of pieces which link as many historical connections as possible through the entire history of Latin America.”27 In a separate letter to collector and patron Olive Bigelow Pell, he lamented that the most important collections of this material live in natural history or folk art museums, underscoring the uniqueness of the DAM’s approach and the importance it played modeling an innovative approach for its peers.28

Noted for his charm and panache, Stroessner forged relationships across the United States and Latin America. Though 1968 was late to be assembling a collection of pre-Columbian art and with few funds at his disposal, Stroessner, like Bach before him, relied on partnerships, museum exchanges, and creative funding. Three collectors played significant roles in building the pre-Columbian holdings: Morton “Buster” May and Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Mayer.

The grandson of David May, a German Jewish émigré who settled in Colorado in 1877, Morton, known as “Buster,” assumed the chairmanship of the May Company department store conglomerate in 1951. While Morton May was born in St. Louis, his roots were in Leadville, Colorado. David May moved his family from Ohio to Leadville for health reasons and established a dry goods supply for the region’s miners. 29 Two years after his arrival, the Leadville mine struck silver, and by 1880, the town had grown to nearly thirty thousand people. Eventually, May would purchase another store in Denver in 1887, and by 1911 the May Department Stores would be a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange. Despite the family’s relocation to St. Louis, the Mays remained a part of Colorado’s Jewish community.30 David May helped found the Hebrew Benevolent Association in Leadville and maintained the town’s synagogue (fig. 8).

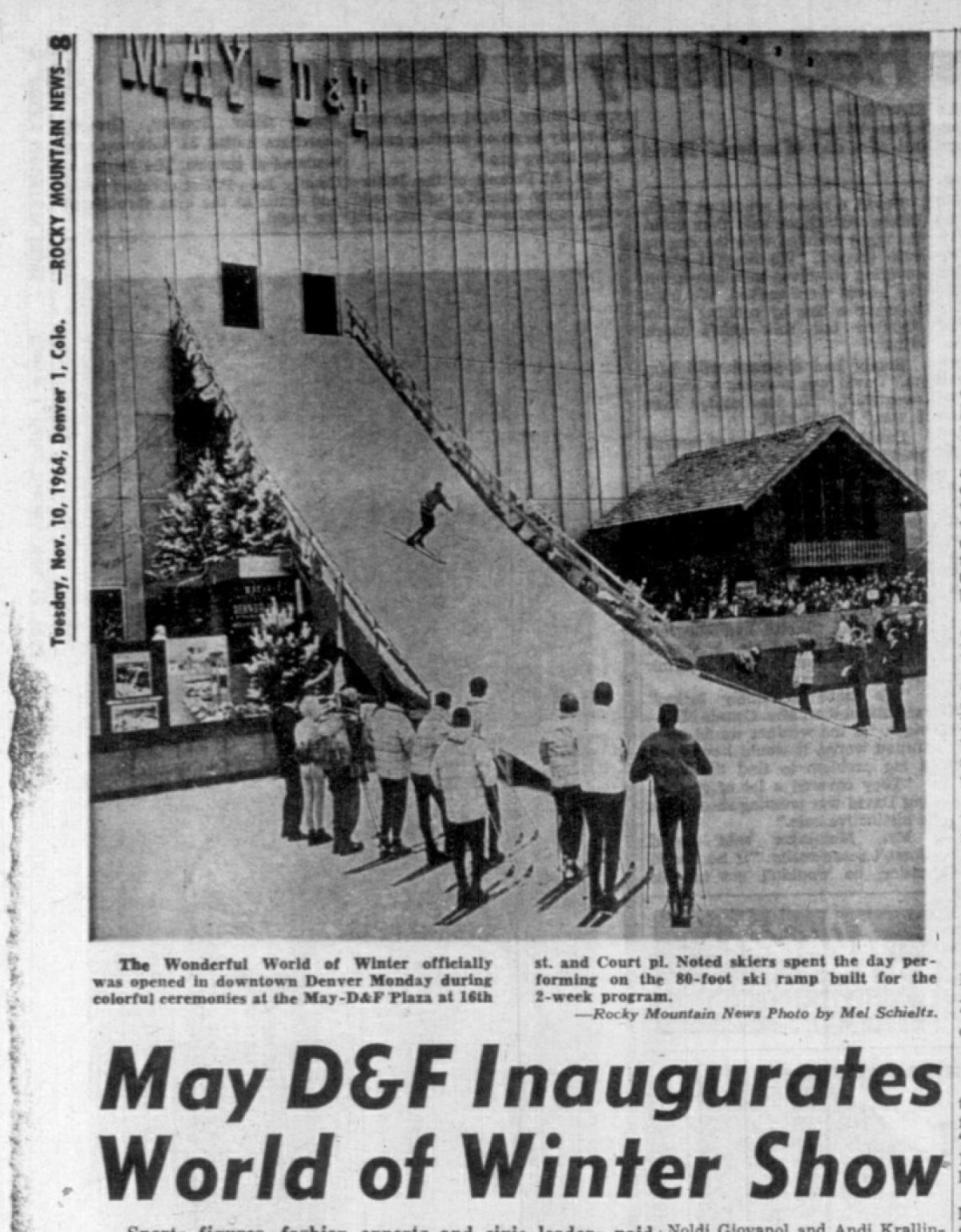

In 1957, the May Company purchased the Daniels and Fischer store on 16th Street in downtown Denver. Known locally as May D&F, the store became a city fixture. Located on Zeckendorff Plaza, the campus included a pavilion shaped like a hyperbolic paraboloid, designed by architect I. M. Pei and an artificial ski slope during the winter months (fig. 9). The structure was destroyed to make way for a pedestrian street mall.

A collector of primitive art, May arrived in Denver just as Otto Bach was trying to rally support for a world-class collection of pre-Columbian art. Indeed, the entirety of May’s documented relationship with the DAM transpired during the course of Bach’s tenure: His earliest gift happened in 1946 and his last in 1971.31 May donated extensively to the Native Arts Department, corresponding with the department’s curator, Norman Feder, and connecting Feder with other collectors and dealers that reached out to May but were not of interest to him.

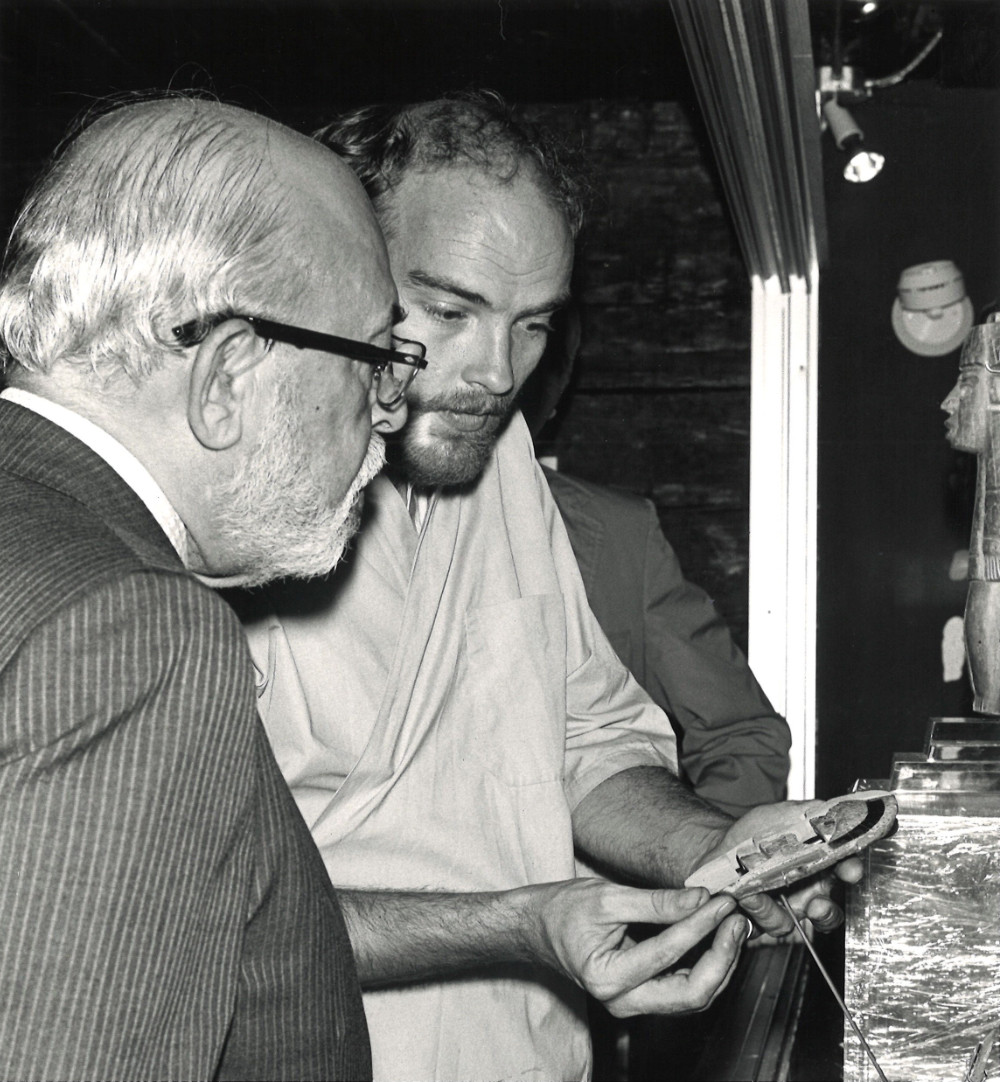

As Matthew Robb’s essay in this volume makes clear, May’s formation as a commercial businessman influenced how he viewed his collections: as commodities that would be bought and sold. This prompted the development of a touring art sale that would visit May Company stores in Saint Louis, Denver and, ultimately, Los Angeles (fig. 10). James Economos, May’s curator and consultant for the art sale, corresponded with curators at institutions nationwide. Economos, May, and the Textile Museum’s curator, Alan Sawyer, were photographed in the courtyard of the May Company’s Wilshire Boulevard department store, and the brazier in Economos’s hand (DAM 1990.70) ended up in the DAM collection via the Los Angeles dealer Earl Stendahl (see figure 7 in Robb).32 In 1969, Morton May gifted the DAM thirteen pieces of Mesoamerican art in honor of David S. Touff, who retired as the May Company board chairman that year.33 Between 1968 and 1971, May and the Denver branch of May D&F were frequent donors to the DAM’s nascent New World Department, directly gifting the museum over fifty individual works.34

In fact, in Bach’s obituary, then board chair Frederick Mayer recalled how he, May, and Bach worked together to build the ancient Americas collection and create the New World Department: “Buster May of the May Co. department stores had a large collection of Peruvian pre-Columbian pieces and Otto pestered him for years to get the collection for DAM. . . . Buster always told him the pieces were for sale not donation. . . . Finally, the store decided to get rid of the collection and Bach negotiated a price of 30,000 for 800 Peruvian pots and textiles.”35 The acquisition was more complex than this and included a substantial gift by Frederick and Jan Mayer to the museum. May’s collection numbered 1,300 works of ancient Peruvian art. May was willing to sell the collection to the DAM at a discounted price, but the museum lacked the necessary funds. Frederick Mayer purchased the entire collection and gifted sixty-two pieces, selected by Bach and Stroessner, to the DAM. Forty-four pieces went to a Texas collector, and the remaining objects were gifted or sold.36 The Andean material included in this acquisition may have come from the enormous Peruvian collection assembled by Dr. Edouard Gaffron and acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago (see Elizabeth Pope, this volume), parts of which had been deaccessioned and purchased by Morton May.37 This complicated transaction, which began in 1969 and was completed in 1970, became one of the New World Department’s foundational collections.38

By 1969, the New World collection had grown sufficiently to occupy dedicated galleries in the new Ponti building, which opened to the public in 1971. Stroessner used his background in interior design to present the newly enlarged collection in dramatic installations, winning over patrons and visitors alike. Large-scale maquettes of Uxmal’s Magician’s Pyramid (fig. 11) and a Maya-period room (fig. 12), complete with painted moss, evoked the magnificence of the material for Denver audiences.

Stroessner’s greatest contribution, however, would be the cultivation of a young couple from Texas, Frederick and Jan Mayer, who would go on to endow the department (fig. 13). The Mayers were early supporters of Stroessner and eventually became the department’s most significant donors. From an early age, Frederick had collected Costa Rican stamps and had been interested in Central America.39 In 1966, he and his wife vacationed in Costa Rica. “In those days,” he recalled, “there were stores that sold pre-Columbian artifacts.”40 The couple focused their collecting on art from this region in an effort to assemble a comprehensive collection of ancient Costa Rican art. Mayer would enlist the help of archaeologists and students to not only find works but to promote the investigation and understanding of the region’s development. Mayer’s intellectual curiosity knew no bounds, and he collected with almost scientific precision. Like May, he amassed all examples of a given style, period, or type, in this case, ceramics, greenstone, and metallurgy from the Costa Rican region. The size and comprehensiveness of the collection gave it an inestimable educational value for scholars of Central America. During the 1980s and ’90s, the Mayers funded numerous studies, symposia, and exchanges between Costa Rican and American students and scholars. Frederick served as Chairman of the Board of Trustees for many years, and his generosity was not limited to the department or even to the DAM.41

The Mayer Center for Ancient and Latin American Art

Beginning in the early 1990s, a large portion of the Mayers’ collection of three thousand pieces were placed with the museum on long-term loan and were featured prominently in the department’s re-installed galleries, which opened in 1993 in time for the museum’s centennial.42 The new installation, geared toward scholars, dedicated nearly half of the floor space to study storage. Seven cruciform-shaped glass cases displayed nearly 90 percent of the ancient Americas collection. Arranged from Inca to the Olmec, the cases displayed many of the works flat on shelves with maps and other didactic material available on the perimeter walls (fig. 14). The arrangement permitted the viewing and comparison of pieces often relegated to storage that the public could not access.

The Mayers funded the creation of a Center for Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art in 2001, the second and successful iteration of such a center. The earlier version, the Center for the Study of Latin American Art and Archaeology, had been staffed by archaeologists, Gordon McEwan, an Andean specialist, and Fred W. Lange, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who focused on Mayer’s region of interest, Central America. McEwan had been appointed New World curator after Stroessner’s passing in 1991 and oversaw the 1993 reinstallation; he left the museum in 1997. Dorie Reents-Budet served as interim curator for two years, overseeing the restitution of a wooden Maya lintel from El Tzotz to the National Museum of Guatemala. Finally in 2001, the DAM decided to split the New World Department into two separate collections overseen by dedicated specialists. Margaret Young-Sánchez became the curator of pre-Columbian art and Donna Pierce the curator of Spanish colonial art.

Young-Sánchez and Pierce, together, shaped what would become the Mayer Center. Both curators added significantly to their respective collections, enhancing the breadth and quality of the New World Department.43 While both organized impactful international exhibitions, Tiwanaku (2002) and Painting a New World (2004), arguably their greatest contribution was shaping the identity and vision of the Mayer Center and its associated activities. The Center’s purpose was, and remains, to increase awareness and promote scholarship in these fields by sponsoring academic activities, including symposia, fellowships, conservation, and publications. The generosity of the Mayers ensured that the symposia could bring together scholars from across the world, galvanizing conversations across disciplines and institutions.

By 2017, the DAM hired two new curators to succeed Young-Sánchez and Pierce, Jorge Rivas Pérez and myself. Together, we decided to revamp tradition by considering the relevance of our respective collections to present communities.44 As we entered the museum’s next phase, the reinstallation of the permanent collection galleries, we reevaluated the antiquated terms used to describe our collections and reaffirmed our commitment to promoting art of the Americas, replacing “pre-Columbian” and “Spanish colonial” with “ancient American” and “Latin American.” While the ancient Americas collection primarily focuses on objects produced during the four thousand years of civilization preceding the Spanish, its expanded scope includes works by contemporary artists whose practice or technique resonates with those of ancient artists.

The reinstallation, completed in 2021, no longer includes the study storage cases (fig. 15). The glass shelves that showcased so many objects intimidated visitors and were replaced with a color-coded presentation structured around geography (Mesoamerica, Central America, and South America) and three central ideas: land, legacy, and trade. The question of “land” addresses the impact that environment, geography, and landscape have on our understanding of the world and our place in it. From volcanoes to mangroves and coastal deserts, the varied landscapes of the Americas played a powerful role in the narratives and cosmovision of peoples across the continent. “Legacy” considers how the past continues to shape the present. The images, shapes, forms, and materials of ancient artists persist in the work of contemporary artists and the visual vocabulary of descendant communities on both sides of the border. Finally, the concept of “trade” addresses the continual exchange of goods and ideas that linked ancient communities across time and space. Recent scholarship has underscored the sophistication of ancient navigation and technological innovation that permitted connections to be made across vast, previously unimaginable, distances.45

Today, the department continues to embrace the groundbreaking approach of the early curators who respected and regarded in the highest esteem the works of Indigenous artists from the Americas. Bach and Stroessner’s vision for a holistic approach that presented the historical and artistic complexity of the region across time has likewise left an indelible mark. But perhaps the strongest influence for the ancient Americas collection at present is the relationship to the descendant communities locally, nationally, and internationally that seek solace and connection in the works of ancient artists.

I am indebted to Paula Michelle Contreras, Ancient Americas Curatorial Assistant, for extraordinary research skills and to the members of the Provenance Team, Lori Iliff, Renée Albiston and Mac Coyle, for their investigative efforts. Additional thanks to Andrea Hansen, Denver Art Museum’s librarian, and Maura Pasquale, former Executive Assistant to the Director, for their guidance on navigating both the department and executive archives. Additional thanks to Renée Miller and Christina Jackson for their help tracking down and resizing hard to find newspaper and magazine images.

Notes

-

Neil Harris, “Searching for Form: The Denver Art Museum in Context,” in The Denver Art Museum: The First Hundred Years, ed. Marlene Chambers (Denver Art Museum, 1996), 60. ↩︎

-

Saint Louis Art Museum: 847 miles; Art Institute of Chicago: 1,006 miles; Dallas Museum of Art: 796 miles; Phoenix Art Museum: 863; LACMA: 1,025 miles. ↩︎

-

Municipal Facts (1929), quoted in Marlene Chambers, “First Steps Toward an Art Museum: The Artists’ Club,” in The Denver Art Museum, 25. ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Duncan, “Anne Evans,” Colorado Encyclopedia, History Colorado, accessed September 2024, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/anne-evans. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ned Blackhawk et al., Report of the John Evans Study Committee (Northwestern University, 2014), https://www.northwestern.edu/provost/about/committees/study-committee-report.pdf; Richard Clemmer-Smith et al., University of Denver John Evans Study Report (2014), https://digitalcommons.du.edu/evansreport/1. ↩︎

-

Douglas served as director of the DAM from 1940 to 1942 before being sent to fight on the Pacific Front. ↩︎

-

Frederic Douglas and René d’Harnoncourt, Indian Art of the United States (Museum of Modern Art, 1941). ↩︎

-

Frederic H. Douglas to Otto Karl Bach, writing from New Hebrides, September 9, 1944, Folder 5, Otto Karl Bach 1944–, Correspondences, Native Arts, Denver Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Frederic H. Douglas to Otto Karl Bach, writing from New Hebrides, October 31, 1944, ibid. ↩︎

-

Frederic H. Douglas to Otto Karl Bach, writing from New Hebrides, November 25, 1944, ibid. ↩︎

-

Bill Hornby, “A Fine Art Museum Does Not Just Happen,” The Denver Post, June 26, 1990. ↩︎

-

Otto Karl Bach to Frederic H. Douglas, writing from Denver, September 18, 1944, Folder 5, Otto Karl Bach 1944–, Correspondences, Native Arts, Denver Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Now known as the Martin Building, the edifice underwent an extensive renovation from 2017 to 2021, and the permanent collections were completely reinstalled. ↩︎

-

Meeting of the Board of Trustees Minutes, July 23, 1956, Board Minutes 1956–59, D12.FB5, Denver Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Ibid. Richard Conn replaced Douglas as Curator in charge of the Native Arts Department. ↩︎

-

Lewis Wingfield Story, “Building a Collection” in The Denver Art Museum, 99. ↩︎

-

Otto Karl Bach, “‘Lost’ Cities Exhibit Opening,” Rocky Mountain News, March 20, 1960, p. 26A. ↩︎

-

Otto Karl Bach, “Early Gold Creations Placed on Exhibit at Denver Museum,” The Denver Post, January 30, 1951; Otto Karl Bach, “Peruvian Art Forms on Display,” The Denver Post, June 29, 1952. The exhibition was presented in the Schleier Memorial Gallery from September 16 to October 4, 1960. ↩︎

-

An accession report mentions Mexican art purchases from Julius Carlebach (Olmec-Totonac incense burner) and Earl Stendahl (Tarascan pottery dog, Colima, Mexico), for example. See Accessions Report, February 16, 1955, Board Minutes 1949–55, D12.FB4, Denver Art Museum Archives ↩︎

-

Otto Karl Bach, “Ancient Mexican Ceramics Acquired by Art Museum,” The Denver Post, June 21, 1959. ↩︎

-

In the director’s report delivered during a 1967 April board meeting, Bach discussed recent museum accessions, all in the field of pre-Columbian art. Since accession funds were zero and had been since the Development Fund campaign started, the only way to keep the collection alive was to trade or exchange material. In this case, Bach traded or exchanged duplicate prints from the museum’s collection in order to acquire an early Peruvian cup (1967.107), a rare Nayarit village Dance (1967.109), a small and costly Maya figure (1967.108), a Costa Rican incense burner representing the crocodile god (deaccessioned), a Costa Rican animal effigy jar (deaccessioned), a snake-headed jar (deaccessioned), and a ceremonial metate in the shape of a jaguar (deaccessioned). Board Meeting, April 26, 1967, Board Minutes 1966–1967, D13.FB1, Denver Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Mr. Billmyer, a member of the board, offered “random thoughts and questions” regarding the museum’s Accession Committee during the meeting held on May 24, 1967. He asked whether the DAM should continue to be a collecting institution, “since it is always suffering from a lack of acquisition funds.” And he personally deplored the idea of “trading,” so he asked for a published statement regarding the museum’s policy and purpose of acquiring art objects. Board Meeting, May 24, 1967, ibid. ↩︎

-

This figure was compiled by reviewing the annual reports and inventory of objects included for each department. Because of the chaotic nature of trades and exchanges that did not always leave a legible trace in the collections record, we found these lists to be more reliable. In the 1967 Annual Report, New World appears as one of the departments, but no specific works are listed. ↩︎

-

Lewis Wingfield Story, “Building a Collection,” in The Denver Art Museum, 103. ↩︎

-

Ibid. A memo listing museum staff in March 1968 notes that the institution employed thirty-three people as staff and lists Robert Stroessner as Assistant Curator of American Indian Art. Annual Meeting Minutes 1968–69, D13.FB2, Denver Art Museum Archives. While born in Colorado, Robert Stroessner’s family had connections to Latin America. A part of Stroessner’s family emigrated from Germany to Colorado, while another branch moved to Paraguay. Alfredo Stroessner, Paraguay’s longtime dictator, was Robert’s granduncle. The family remained in contact with their South American relatives. Stroessner visited Paraguay, and on at least on one occasion, his granduncle visited the US. See La Hay Wauhillau, “Denver’s Stroessner Rub Shoulders with President,” The Denver Post, March 21, 1968. It is not known, however, how much Robert or his parents knew of his granduncle’s activities in the country. See also “Remembrance of Robert Stroessner” by Teddy Dewalt sent to Anne Tenant, Mayer Center Archive, Denver Art Museum. The Mayer Center Archive encompasses archival material for both Arts of the Ancient Americas and Latin American Art as well as the previous New World Department. ↩︎

-

Robert Stroessner to Tom Maytham, October 15, 1974, Stroessner Files 1974, Correspondence, Mayer Center Archive. ↩︎

-

Robert Stroessner to Olive Bigelow Pell, November 12, 1968, Stroessner Files, 1968, ibid. ↩︎

-

“David May: Pioneer Jewish Merchant, Founder of May Company and His Family,” Jewish Museum of the American West, May 16, 2014, https://www.jmaw.org/david-may-may-co/. See also The May Company/David May, 1952–1979, Box 1, Mercantile, Beck Archives Businesses Collection, B112.03.0001.0010, University of Denver Special Collections and Archives. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

The first piece gifted to the DAM was Joe Jones’s painting Departure (1938; 1946.20) on August 5, 1946. The last piece would be a Papuan New Guinea Gulf Table on January 31, 1971 (1971.719). ↩︎

-

Thank you to Matthew Robb, who helped identify James Economos and the context of the photograph. The May Company store would ultimately become part of Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s campus and was known as “LACMA West.” It housed various museum departments including publications and education. Other floors would become storage for unused vitrines and museum furniture before the museum leased the building to the Academy Museum. ↩︎

-

Morton May to Otto Bach, August 26, 1969, Morton May files, Saint Louis Art Museum, copy of letter housed in the Mayer Center Archive, Denver Art Museum. ↩︎

-

Stroessner notes the generosity of Morton May and illustrates a number of his gifts in the 1968 Annual Report, Board Minutes 1968–69, D13.FB2, Denver Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Joanne Ditmer, “Otto Bach and His Enduring Legacy,” The Denver Post, December 2, 1990. ↩︎

-

Meeting of the Board of Trustees Minutes, February 18, 1970, Board Minutes 1970–71, D12.FB5, Denver Art Museum Archives. A letter from Robert Stroessner to Morton May, March 12, 1970, acknowledges the details of the sale (May Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum). And a letter from Robert Stroessner to Frederick Mayer, December 7, 1970, expresses his gratitude to Mayer for the gift of sixty-two pieces and includes the inventory of works (Stroessner Files, 1970, Correspondence, Mayer Center Archive, Denver Art Museum). Thank you to John Buxton, who helped track down material from the Texas collector. Alan Sawyer, director of the Textile Museum in Washington, DC, and former curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, provided the valuations of the Andean material. Morton May files, Saint Louis Art Museum, copy of letter housed in the Mayer Center Archive. ↩︎

-

See “Bach years, 1944–1974,” in Denver Art Museum, 294fn47. ↩︎

-

In this history of the Mayers’ involvement with the DAM, this gift stands out for its financial complexity. It is worth noting that there is no evidence that the Mayers ever performed such fiscal feats again to bring a collection to the museum. Given the timing of the exchange, I would speculate that May, a successful businessman fourteen years Mayer’s senior, may have exerted a certain influence on the nature of the purchase and the eventual gift. ↩︎

-

Margaret Young-Sánchez, “Introduction and Acknowledgments,” in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology: Essays in Honor of Frederick R. Mayer, ed. Margaret Young-Sánchez (Denver Art Museum, 2013), 7. ↩︎

-

Richard Johnson, “Art Experts Maintain a Low Profile,” The Denver Post, March 4, 1991. ↩︎

-

Mayer supported both of his alma maters, Phillips Exeter Academy and Yale University, contributing significantly to capital campaigns for museums at both institutions. ↩︎

-

Mary Voetz Chandler, “A Denver Showpiece,” Rocky Mountain News, January 31, 1993. ↩︎

-

Young-Sánchez broadened the collection geographically and materially by acquiring a group of Marajoara works from Brazil, including a funerary urn (2006.14), and several extraordinary textiles, including an Intermediate period textile from southern Peru (2013.448). Pierce added significantly to the department’s holdings of viceregal Mexican material, including notable works such as De Español y Negra Mulato (From Spaniard and Black, Mulatto; c. 1760; 2014.217), Saint Rose of Lima with Christ Child and Donor (c. 1700; 2014.216), and Young Woman with a Harpsichord (1735–50; 2014.209). ↩︎

-

ReVisión: Art in the Americas, a traveling exhibition co-curated by Rivas and Lyall, inaugurated the newly renovated Martin Building in October 2021 and showcased masterworks from both collections in dialogue with contemporary Latin American and Latinx artists. ↩︎

-

For example, see Christopher S. Beekman and Colin McEwan, ed., Waves of Influence: Pacific Maritime Networks Connecting Mexico, Central America, and Northwestern South America (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2022). ↩︎