During the symposium, works sourced from the Stendahl Art Galleries were referred to in almost every presentation, from museum collections in New York to Denver. Particularly before 1970, no other single art gallery or art dealer had such impact in the formulation of museum collections in the area of prehispanic art. At the symposium, scholars evaluated individual institutional histories in the United States, especially those of art museums, with respect to the civic responsibilities shouldered by institutions and the opportunities that different curatorial departments undertook, sometimes with the engaged interest of individual collectors, who sought to bring an institution in line with their own passions.

But none of these collections could have been formed without the leadership of an extraordinary salesman: Earl Stendahl (1888–1966). Stendahl invented the business of prehispanic art. Before 1940, acquiring prehispanic art was often a more touristic and haphazard entrepreneurial endeavor, with little substantial difference between anthropology and art history. Such blurriness was indeed the case once one stepped anywhere outside of European and American collections of painting and sculpture, including the arts of Africa and Oceania. Stendahl marketed to collectors and to museums, and early on, he saw the market value of securing venues that would drive other sales, whether in the permanent collection of the Seattle Art Museum or in the temporary exhibitions he organized locally in southern California and internationally. And eventually there would be other attendant effects: Acquisitions by museums would become core works in survey texts and classroom instruction.1 Stendahl could have taught a course in market development.

We can learn today a great deal about how this market took shape from the letters the family exchanged with one another from the late 1940s until his death in 1966. Stendahl, his son, Alfred (Al; 1915–2010), his wife, Enid (1889–1979), and his son-in-law, Joe Dammann (1922–1971), all participated in the family business and wrote letters to one another, especially when conducting business away from Los Angeles. The Getty Research Institute (GRI) has 357 of these family letters in its holdings in box 105, part of the comprehensive archive of the Stendahl Art Galleries (SAG) business documentation, an archive that comprises stock books, photographs, and extensive correspondence with dealers (e.g., Guillermo Echániz [1900–1965] in Mexico), collectors (e.g., Nelson Rockefeller [1908–1979], founder of the Museum of Primitive Art), and museums (e.g., Dayton Art Institute and its director Thomas Colt [1905–1985]). Held in folders at the end of the archive, and many written on aerograms and other very lightweight paper, these letters have rarely been consulted.2 The information in the letters sheds light on family life, competitors, Los Angeles, and much more. Most of all, this archive underpins the work conducted by the Pre-Hispanic Art Provenance Initiative (PHAPI), dedicated to examining and interpreting the business of selling ancient art of Latin America in the United States and elsewhere.3

Explicit business correspondence was always important to Earl Stendahl and the SAG, and starting in 1940, the gallery grew to become the largest volume seller of prehispanic art in the 1960s in the United States. In 2021, the GRI published eight letters between Earl Stendahl and Guillermo Echániz, written over a period of fifteen months, from October 1940 until January 1942.4 The shipping lanes to Europe and Asia from the United States had closed at the beginning of the period of this correspondence, and by January 1942, the United States was at war with the Axis powers and mail was under federal scrutiny, if not censorship. The SAG was just finding its way to extensive business in Mexico and was dependent on Echániz. These eight letters show the development of the business, cultivating buyers Ambassador Robert Woods Bliss (1875–1962), who had established the museum and research center Dumbarton Oaks, in Washington, DC, with his wife, Mildred Barnes Bliss (1879–1869), and Walter and Louise Arensberg (1878–1954; 1879–1953), who collected modern and pre-Columbian art, as well as the slippery tactics undertaken to remove objects illicitly from Mexican archaeological contexts and move them across the border to the United States. Perhaps because of the nature of the business or perhaps because of the censors, Stendahl and Echániz often wrote in coded references.

The family letters, though, are different—unfiltered and uncoded correspondence written a generation later, when the business was in full swing. But “full swing” did not mean that financial success was certain, even when the Stendahls had developed multiple sources across multiple countries and a worldwide clientele. They established a New York beachhead for the business, and Earl and Enid became well-known at the best hotels in Europe. Mail—and frequently international mail—was the means by which the extended family worked, played, criticized, and supported one another. Although on the surface the family letters are the means of exchanging pleasantries regarding weather, home maintenance, and notes of outcomes from the racetrack, this correspondence is often revealing in the private comments regarding the sales process and the opinions of potential buyers. “I now feel strongly that Jan or February sale is in order. Get what we can out of as much junk as we can sell,” wrote Al to his father, probably in 1957, describing the possibility of some high-volume, low-value sales.5 On paper, Earl was tough on his son, Al, and son-in-law, Joe, grousing about their failure to get accounts paid and paid off. At home in Los Angeles, the gallerists could have registered their complaints in person: From the road, the letter was the recourse.

As revealing as such comments may be, these letters are even more important in their documentation, no matter how oblique, of business practices. The focus of PHAPI is to reveal and link these practices: While stock books and inventories document the formal side of the practice, the family letters point to the ways that three principals—Earl, Al, and Joe—shared different responsibilities, from navigating works across international borders to paying gardeners at the gallery and expressing ire at unpaid invoices with frank comments about friends and competitors. They also kept an eye out for the opinions of archaeologists and art historians. Because the SAG was the single largest vendor of prehispanic art in its heyday, understanding the practices also helps reveal the picture of the many routes by which such works entered art museums. In many ways, working through the SAG archive is akin to discovering a complete archaeological stratum, one known only through the occasional trade object encountered hither and yon. With these records the big picture, year by year, can start to come into focus.

Unlike the data of the stock books, the content of the family letters cannot be summarized: Their level of granular detail resists the big picture, yet no big picture can be drawn without them. The family letters show how Earl was always on the hunt for more and better business, with private collectors and museums across the world—and while cryptic, the letters also show that Earl kept an enormous number of details in his head, juggling purchases in Mexico with sales and purchases in Europe. Failed business deals, rarely noted in the stock books, are a regular feature of the family letters. In these accounts, Earl kept an eye on his two younger partners (who were more typically in Los Angeles) and the competition emerging both nearby and in New York. He kept his “frenemies” close: cajoling and collaborating with them. He expressed bitterness at those sellers abroad, particularly in Mexico, who gave a better deal or first choice to his US competition. And he sought new avenues of promotion—from local exhibitions to what became a Stendahl grand tour of European institutions from 1958 to 1963. For a man who had once been poor, who would turn time and again to his background as a candymaker when times were tough, he had arrived both at home in Los Angeles and beyond.6 By the time of his death in 1966, Earl penned letters home on stationery from glamorous hotels in New York and abroad.

The rest of this essay includes portions of family letters. My glosses and their specific focus point to a larger picture of the SAG practice. The family letters are most dense and interlocking from 1954 until just before Earl’s death in 1966, and so small selections of these letters will be drawn from those years, ending with a letter from December 1965 that reveals a deal the SAG failed to make. Dozens of letters document the five years between 1958 and 1963; addressed briefly elsewhere, those letters focus on developing new markets and new inventory, often of classical antiquities, with much of the business conducted in Europe.7 To keep this essay focused on the prehispanic market in the United States, the letters selected here date from 1954 to 1956 and from 1963 until 1965. Letters from Earl, Al, Joe, and Enid all point to different aspects of the business, and each has a very specific voice, from brusque to chatty, and when speaking of the young children in the family, even tender. Spelling and punctuation rarely meet the standards of the day and are retained here. Dates have been reconstructed, by and large, by the PHAPI project. Full transcriptions of the letters can be found in the Appendix of this volume. The selections that follow have been taken from larger contexts, as seen in the illustration of the original letter in the GRI archives.

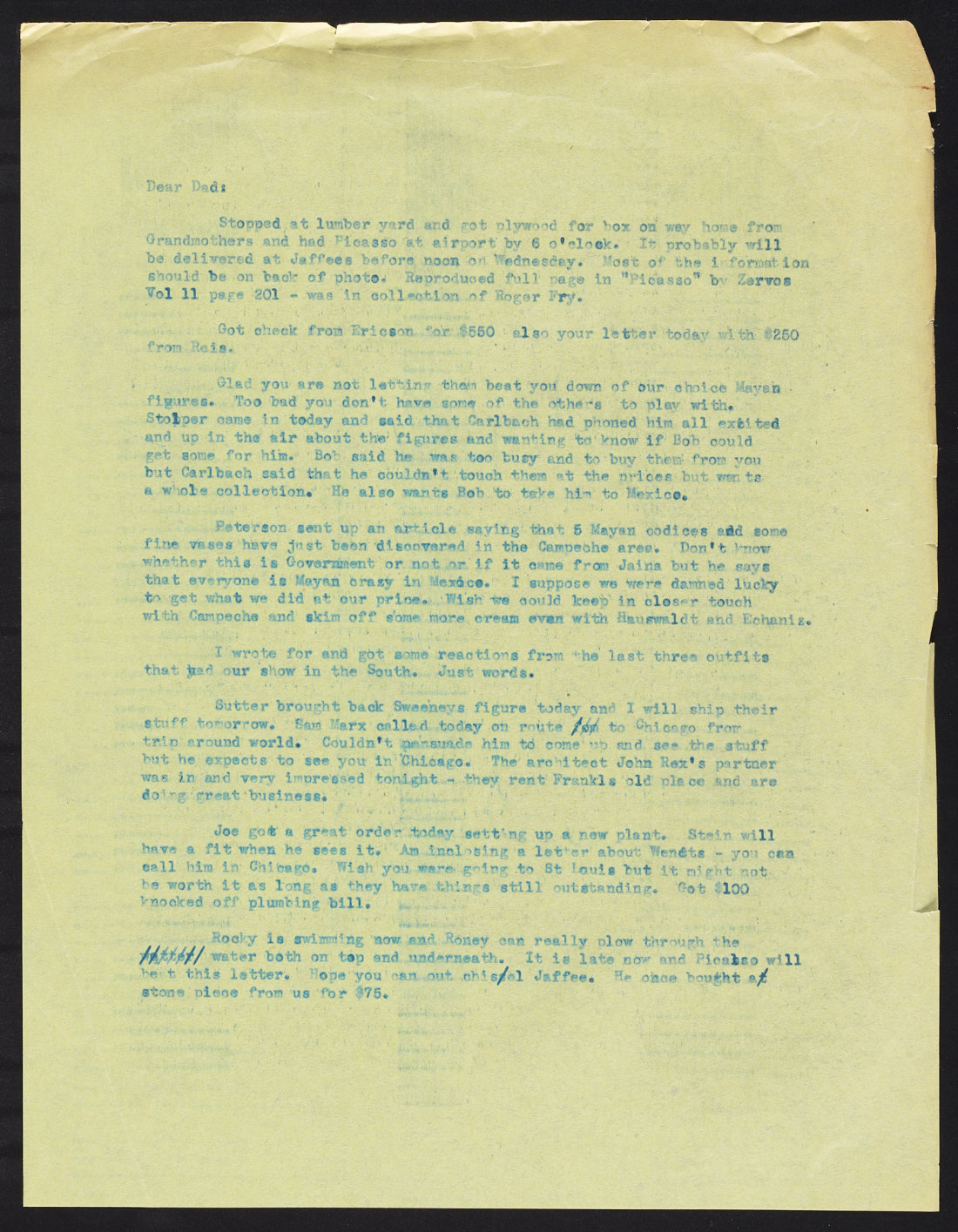

Al Stendahl, in Los Angeles, to his father, Earl Stendahl, in New York, 1954 (month and day uncertain)

Dear Dad: Stopped at lumber yard and got plywood for box on way home from Grandmothers and had Picasso at airport by 6 o’clock. . . .

Stolper came in today and said that Carlbach had phoned him all excited and up in the air about the figures and wanting to know if Bob could get some for him. Bob said he was too busy and to buy them from you but Carlbach said that he couldn’t touch them at the prices but wants a whole collection. He also wants Bob to take him to Mexico.

Peterson sent up an article saying that 5 Mayan codices and some fine vases have just been discovered in the Champeche area. Don’t know whether this is Government or not or if it came from Jaina but he says that everyone is Mayan crazy in Mexico. I suppose we were damned lucky to get what we did at our price. Wish we could keep in closer touch with Campeche and skim off some more cream even with Hauswaldt and Echaniz.

Threaded through the family letters are sales of works by European artists. Here, Al apparently shipped a Picasso out of the Los Angeles International Airport. Did he build the crate for the artwork? The letter is vague on that point.

Robert (Bob) Stolper (1920–2013) worked closely and competitively with the SAG from 1950 until 1970 or so. He sold prehispanic and other works of art in Los Angeles, New York, and London and is the nonfamily member most widely referred to in the family letters. He kept an apartment in Mexico City in the 1960s, perhaps principally for making purchases. He seems to have also kept an apartment at 11 East 68th Street in New York (The Marquand, built in 1913), perhaps adjacent to the Stendahls’ place in the same building. This letter was presumably written in Los Angeles. What seems to have happened is that Julius Carlebach (1909–1964) had called Stolper by telephone from his home and gallery in New York, and Stolper then dropped by the SAG. Al was eager to get it all down on paper to his father. Carlebach sold a diverse “primitive” inventory and purchased extensively from the SAG, as evidenced in the stock books. Given the date of 1954, Carlebach (whose gallery was at 943/937 Third Avenue) would have known the 1952 exhibition Ancient Tarascan Art at the Sidney Janis Gallery, which consisted of loans or works on commission from SAG. There is no known surviving archive of Carlebach today, but he was one of the principal dealers to sell to Fred Olsen (1891–1996), whose prehispanic collection is now at the Yale University Art Gallery.

And who was Frederick Peterson (1920–2009), addressed next in this letter? The author of Ancient Mexico (1959), Peterson was a long-standing faculty member at the University of West Virginia, who had documented thousands of prehispanic objects in both public and private collections in the 1950s; one copy of his documentation survives today at the University of New Mexico.8 He was well connected in both Mexico and the United States, and fake Maya codices, as discussed in this letter, circulated both in 1954 and today.9 In what might seem to be a non sequitur, the letter connects the codices to Jaina Island (an unlikely origin, all in all), and April Dammann has recounted how Earl secured permission to film on Jaina Island in 1952.10 He and his crew then proceeded to loot the island for a month, filling oversized cases with dozens, if not hundreds of figurines—so he was “damned lucky” with his timing, as Al noted in the letter, especially as interest in Maya art ramped up: Robert Woods Bliss and Nelson Rockefeller had both made significant acquisitions of Maya objects by then. “Campeche” is probably a shorthand reference to one of the Stendahl’s Mexican partners operating in Yucatan, probably Alberto Márquez or less likely José Maria Palomeque, to stay ahead of other buyers, particularly Jorge Hauswaldt, a German émigré in Mexico, and Echániz, Earl’s principal Mexican partner.

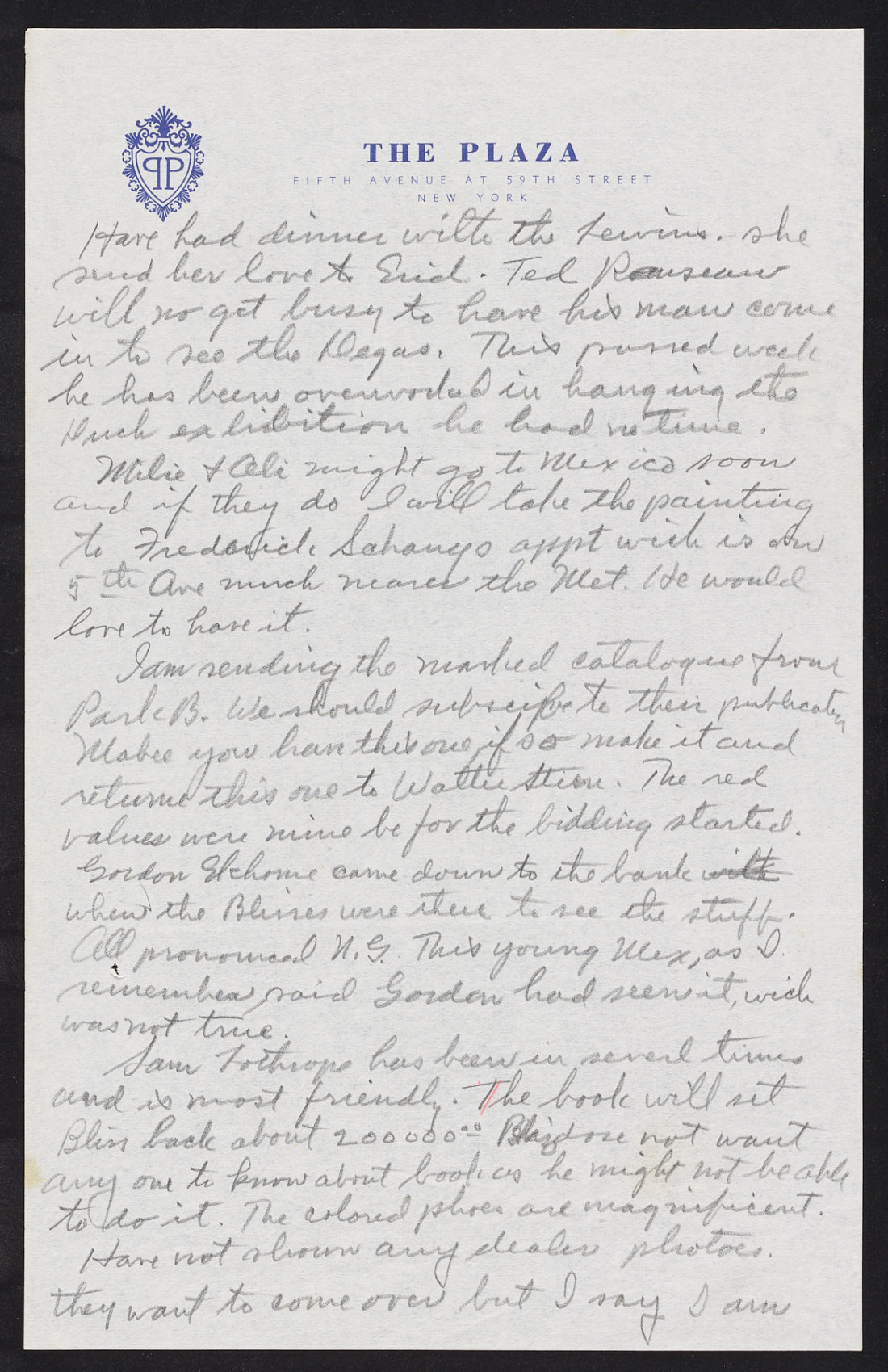

Earl Stendahl, in New York, to his son, Al Stendahl, in Los Angeles, Friday, October 29, 1954 (dated by Earl)

(On page 4 or 5 of what appears to be a six-page letter)

. . . Gordon Eckholm came down to the bank

withwhen the Blisses were there to see the stuff. All pronounced N. G. This young Mex, as I remember, said Gordon had seen it, wich was not true.

Sam Lothrop has been in several times and is most friendly. The book will set Bliss back about 200000.00. Bliss dose not want any one to know about book as he might not be able to do it. The colored phoes are magnificent. . .

Several advisers and authenticators played key roles with respect to the quality and integrity of the Stendahl inventory. One of the most important individuals to dealers and collectors in New York was Gordon Ekholm (1909–1987), Mesoamerican curator at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), who also advised Ernst Erickson (1893–1983) on building the collection Erickson would donate to the AMNH.11 Presumably written in New York, this six-page letter, written over multiple days, noted that Robert and Mildred Bliss came to examine works in a bank vault with Ekholm and perhaps a “young Mexican,” although it is hard to follow the timing. The “young Mexican” might be Jose Luis Franco, the Mexican authenticator with whom Ekholm was friendly and who may have been involved in the export of antiquities at some point. Although dated 1954, at this point, Bliss was already planning the book that would be published in 1957, Pre-Columbian Art: Robert Woods Bliss Collection, written by Samuel K. Lothrop, Joy Mahler, and William Foshag, a spectacular coffee table book featuring the Bliss collection. Earl has this book in mind as he begins to plan the publication Pre-Columbian Art of Mexico and Central America, published posthumously by Harry N. Abrams (1968).

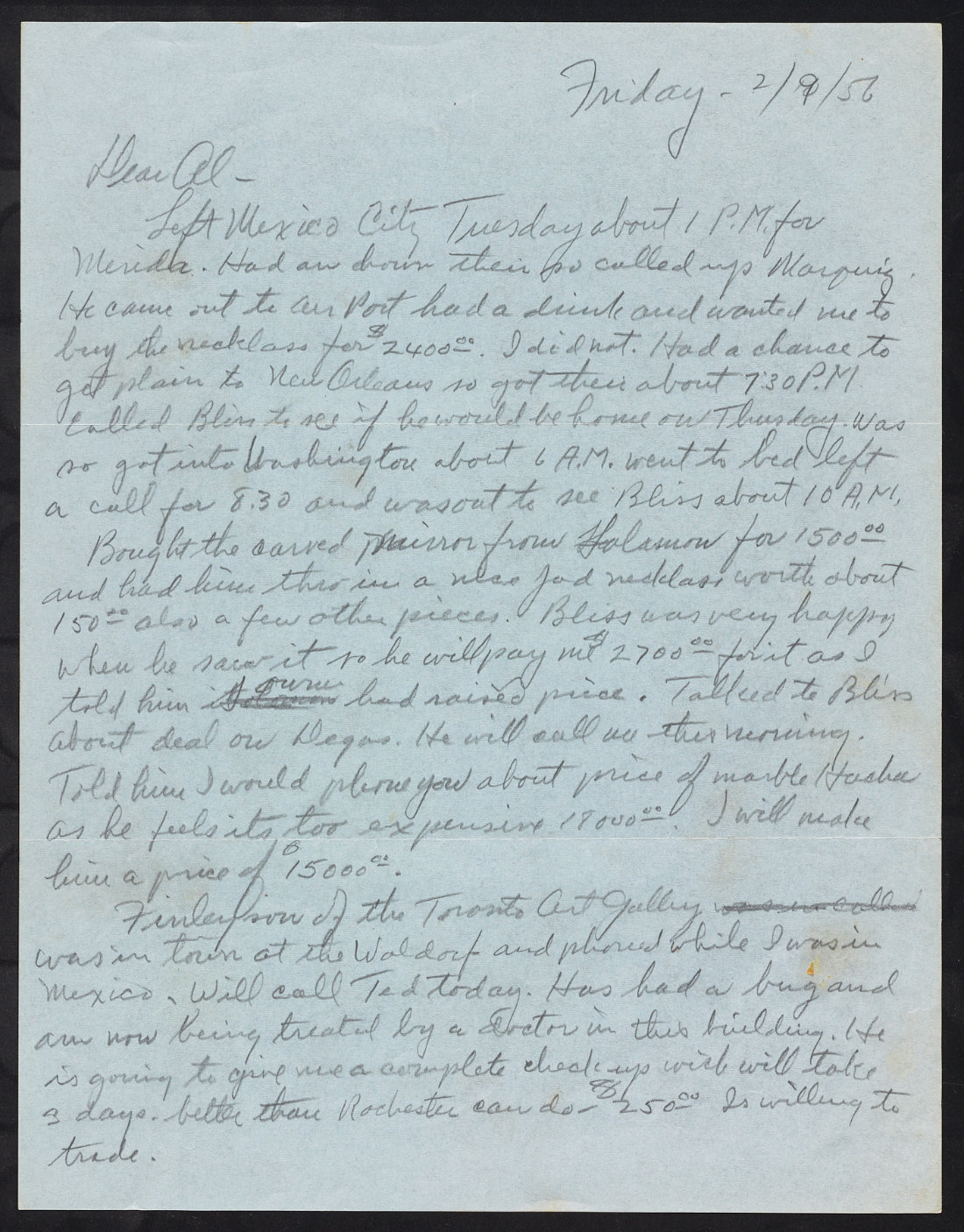

Earl Stendahl, in New York or Washington, to his son, Al Stendahl, in Los Angeles, February 9, 1956

Dear Al –

Left Mexico City Tuesday about 1 P.M. for Merida. Had an hour their so called up Marquez. He came out to the air port had a drink and wanted me to buy the necklace for $2400.00. I did not. Had a chance to get plain to New Orleans so got there about 7:30 P.M. Called Bliss to see if he would be home on Thursday. Was so got into Washington about 6 A.M. Went to bed left a call for 8:30 and was out to see Bliss about 10 A.M.

Bought the carved mirror from [indecipherable, possibly Hauswaldt or Solamon] for 1500.00 and had him thro in a nice jad necklass worth about 150.00 also a few other pieces. Bliss was very happy when he saw it so he will pay me $2700.00 for it. . . . Talked to Bliss about deal on Degas. He will call me this morning. Told him I would phone you about price of marble Hacha as he feels its too expensive 18000.00. I will make him a price of $15000.00. . . .

Earl continued to pursue Maya art, using a short layover in Merida, Mexico, to meet with Alberto Marquez, a source for him there (Earl declined to purchase a necklace), en route to New Orleans and up to Washington, DC, to see Robert Woods Bliss, perhaps his most significant client. The Degas painting at Dumbarton Oaks today (HC.P.1918.02.(O)) was not acquired from Stendahl, so this sale evidently did not take place. The items that Earl showed to Bliss were things he had presumably brought from Mexico City in his luggage, acquired from someone whose name cannot be easily deciphered. He quickly made $1,200 on the deal, selling Bliss the carved mirror (also not a work at Dumbarton Oaks today), and although he told Bliss he would consult Al on a price reduction, he simply informed Al that the price on a “marble” hacha (presumably PC.B.038) would drop by $3,000.

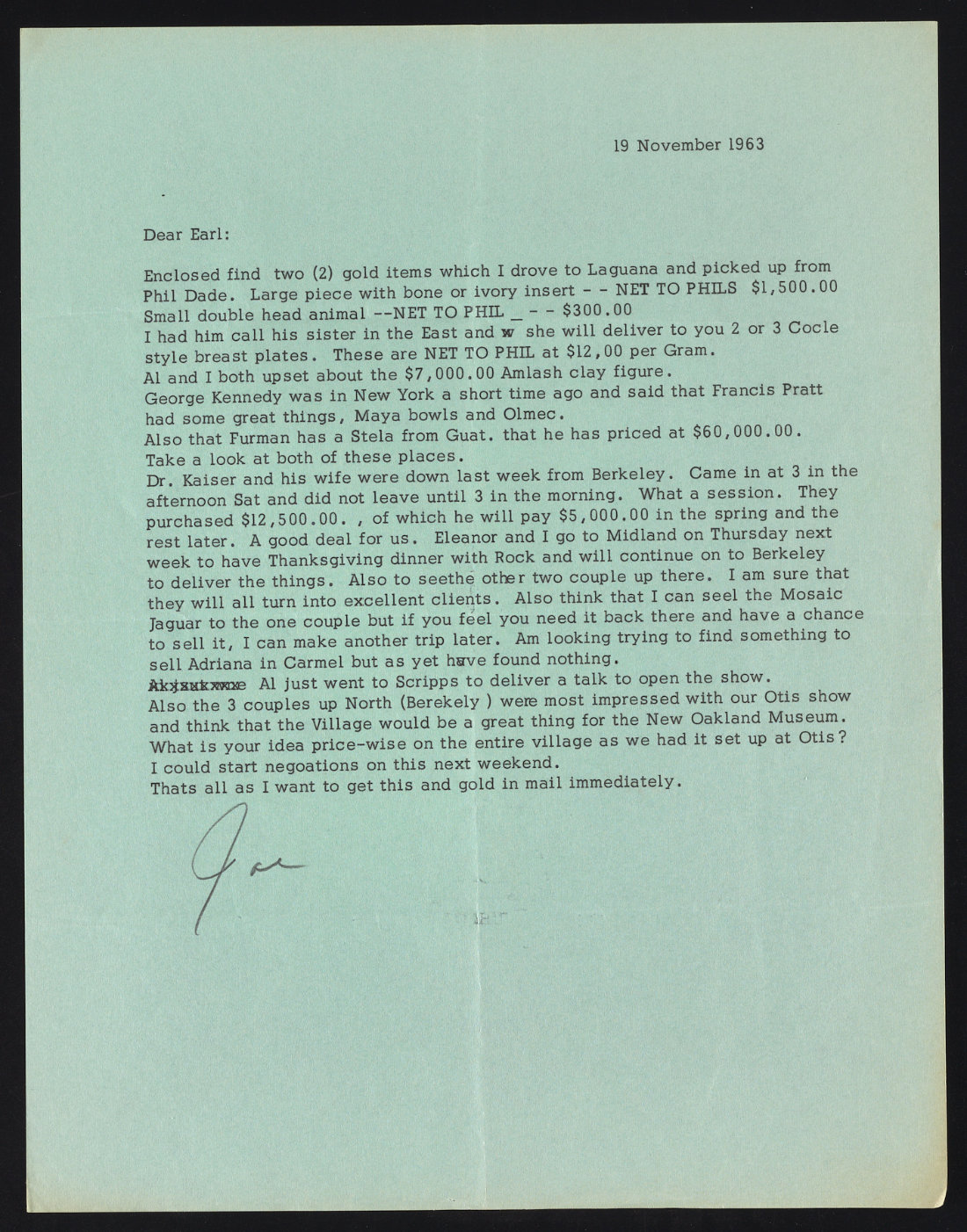

Joe Dammann, in Los Angeles, to his father-in-law, Earl Stendahl, in New York, November 19, 1963

. . . George Kennedy was in New York a short time ago and said that Francis Pratt had some great things, Maya bowls and Olmec.

Also that Furman has a Stela from Guat. that he has priced at $60,000.00. Take a look at both of these places.

Dr. Kaiser and his wife were down last week from Berkeley. Came in at 3 in the afternoon Sat and did not leave until 3 in the morning. What a session. They purchased $12,500.00., of which he will pay $5,000.00 in the spring and the rest later. A good deal for us. Eleanor and I go to Midland on Thursday next week to have Thanksgiving dinner with Rock and will continue on to Berkeley to deliver the things. Also to seethe other two couple up there. I am sure that they will all turn into excellent clients. Also think that I can seel the Mosaic Jaguar to the one couple but if you feel you need it back there and have a chance to sell it, I can make another trip later. Am looking trying to find something to sell Adriana in Carmel but as yet have found nothing.

Al just went to Scripps to deliver a talk to open the show.

. . . Thats all as I want to get this and gold in mall immediately.

Written four days before the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, this letter elucidates how Earl’s son-in-law, Joe Dammann, is thinking about the SAG’s new inventory and new competition. Regardless of the context, the SAG picked up useful intelligence from their clients. Noted in this letter is George Clayton Kennedy (1919–1980), who bought from the SAG but also from other dealers, especially in New York, including Frances Pratt (1913–2003), a dealer at 31–33 West 12th Street in Greenwich Village.12 But the big news was about Aaron Furman (1900–1975), who probably sold more African and contemporary art than prehispanic art in his gallery at 46 East 80th Street: In this letter, he had a Maya stela from Guatemala for sale for $60,000. An increasing number of dealers were working from New York in the 1960s and focusing on Maya and Olmec inventory.

The key new client here is Dr. William F. Kaiser of Berkeley, who spent $12,500 in twelve hours. One can only imagine the party that ended at 3 a.m. Joe described how he would seal the deal by delivering the acquisitions to Dr. Kaiser in person in a few days. He also had plans to visit other new clients. Works from the collection of Dr. and Mrs. Kaiser are periodically sold at auction; a notable Zapotec urn from the collection was drawn by Adam Sellen.13

Joe also describes a plan to sell the Mosaic Jaguar, a work eventually published in Saturday Evening Post on February 8, 1964, to accompany the article “Art from Nobody Knows Where” that detailed the rampant looting in Mexico that was feeding prominent collections in the US despite Mexican laws prohibiting it. The Mosaic Jaguar was actually a blatant forgery, and its location is not known today.

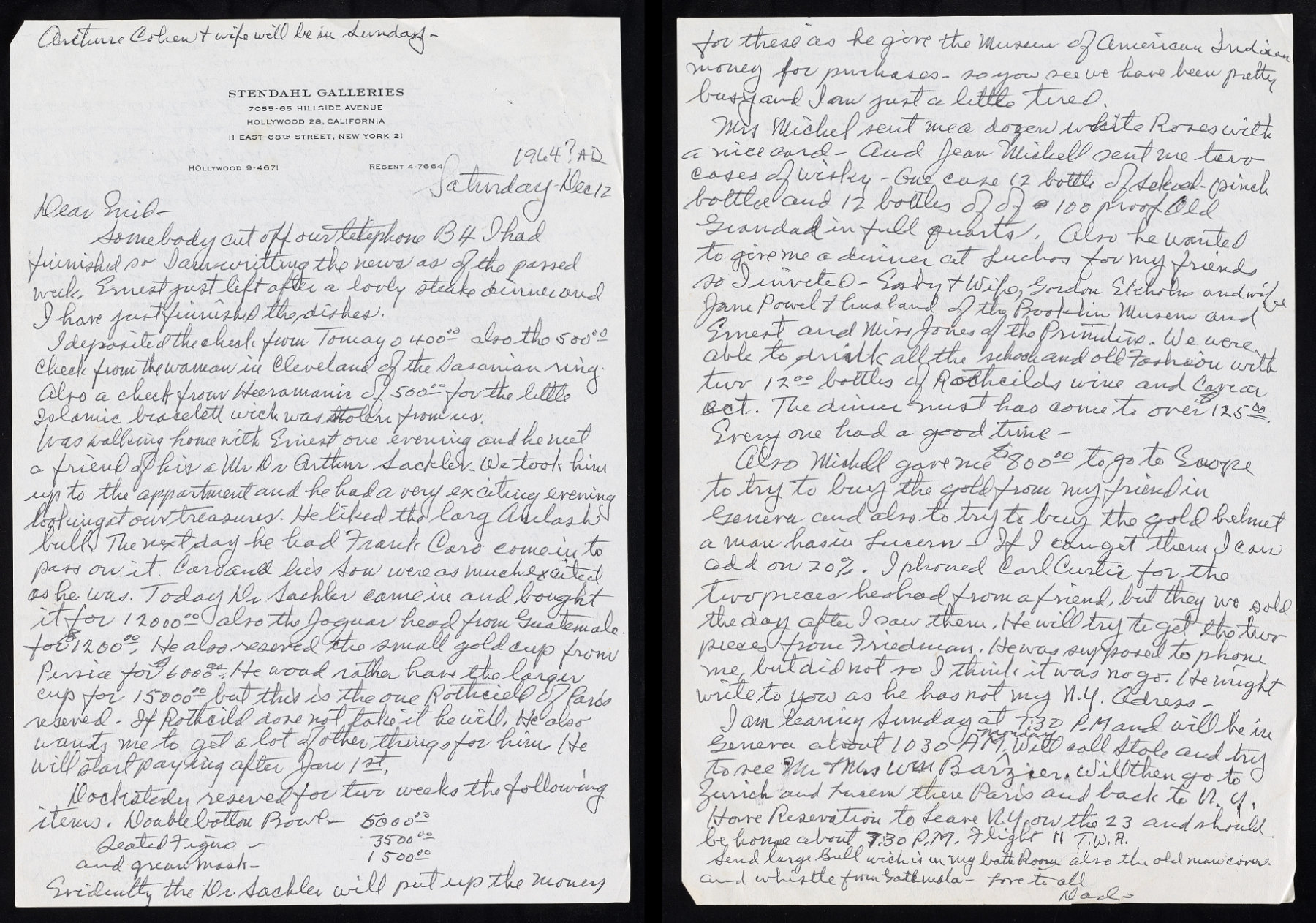

Earl Stendahl, in New York, to his wife, Enid Stendahl, in Los Angeles, December 12, 1964

Dear Enid– Somebody cut off our telephone B4 I had finished so I am writting the news as of the passed week. Ernest just left after a lovely steak dinner and I have just finished the dishes.

I deposited the check from Tomayo 400.00 also the 500.00 check from the woman in Cleveland of the Sasanian ring. Also a check from Heeramanic of 500.00 for the little Islamic bracelett wich was stolen from us.

Was walking home with Ernest one evening and he meet a friend of his a Mr Dr Arthur Sackler. We took him up to the appartment and he had a very exciting evening looking at our treasures. He liked the larg Amlash bull. The next day he had Frank Caro come in to pass on it. Caro and his son were as much excited as he was. Today Dr Sackler came in and bought it for 12000.00. . . . He also reserved the small gold cup from Persia for $6000.00. He woud rather have the larger cup for 15000.00 but this is the one Rothchild of Paris reserved. . . .

Evidently the Dr Sackler will put up the money for these as he give the Museum of American Indian money for purchases-so you see we have been pretty busy and I am just a little tired.

Mrs Michel sent me a dozen white Roses with a nice card–and Jan Michell sent me two cases of wiskey–one case 12 bottle of scotch pinch bottles and 12 bottles of of 100 proof Old Grandad in full quarts. Also he wanted to give me a dinner at Luchos for my friends so I invited Easby & wife, Gordon Ekholm and wife Jane Powel & husband of the Brooklin Museum and Ernest and Miss Jones of the Primitive. We were also to drink all the schoch and Old Fashion with two 12.00 bottles of Rothchilds wine and caviar ect. . . .

. . . Will then go to Zurich and Lucern there Paris and back to N.Y. Have Reservation to leave N.Y. on the 23 and should be home about 7:30 P.M. Flight 11 T.W.A

Send large Bull wich is in my bath Room also the old man cover and whistle from Gotemala–Love to all

Dad

A year later, things were on the up and up; Lyndon B. Johnson had been elected president in his own right, and the economy was booming. Earl wrote to Enid from New York, in the apartment the SAG leased at 11 East 68th Street. He had just had dinner, apparently in his own apartment, with Ernest Erickson, the single greatest patron of prehispanic art in this period at AMNH.14 The woman in Cleveland may be Mrs. Emery Norweb, a trustee at the Cleveland Museum of Art (see Bergh, this volume). This letter is further evidence of the SAG relationship with the Heeramanecks, major dealers in Los Angeles and New York, particularly of South and Southeast Asian art. Today the Heeramaneck collection of prehispanic art is in the National Museum, New Delhi, India, the sole such collection in that nation.

The story that Earl went on to relate to his wife is downright picaresque, a litany of key New York players in the art world: Erickson introduced Earl to Dr. Arthur Sackler (1913–1987), and they had a fine time examining works in the Stendahl apartment, particularly an Amlash Bull. Sackler subsequently brought his own art consultant, Frank Caro, a Chinese specialist, to advise him. What follows points to, without fully explaining, fuzzy documentation at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI).15 Frederick Dockstader (1919–1998), director of the Museum of the American Indian, came to see Stendahl, ordered up $10,000 worth of objects, and Dr. Sackler was said to be footing the bill. Earl considered himself lucky, especially in the gifts that his clients also sent him, suggesting the exchange economy between gallerist and collectors: Mrs. (Daniel) Michel of Chicago sent him a dozen roses, and Jan Mitchell sent him two cases of whiskey.16

Mitchell then threw a dinner party at Lüchow’s, his famous New York establishment near Union Square, with the Easbys and Ekholms in attendance, as well as Jane Powell (and husband) of the Brooklyn Museum, Julie Jones, curator of pre-Columbian art at the Museum of Primitive Art, and Ernest Erickson. Dudley and Elizabeth Easby (1905–1973; 1925–1992) were important figures in New York; Dudley was a Metropolitan Museum trustee, and Elizabeth would be one of the curators of Before Cortes: Sculpture of Middle America (1971), a signature exhibition of prehispanic art in New York. Jane Powell (1930–1993) left the Brooklyn Museum after a short stint there and is better known as Jane Dwyer from her days as director of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology at Brown University. Julie Jones (1935–2021) would go on to become the head of the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at The Met for twenty-one years and curator emeritus until her death in 2021.

The letter concludes with Earl’s travel schedule for the next ten days or so in Europe and a request to Enid to ship Los Angeles inventory on to New York.

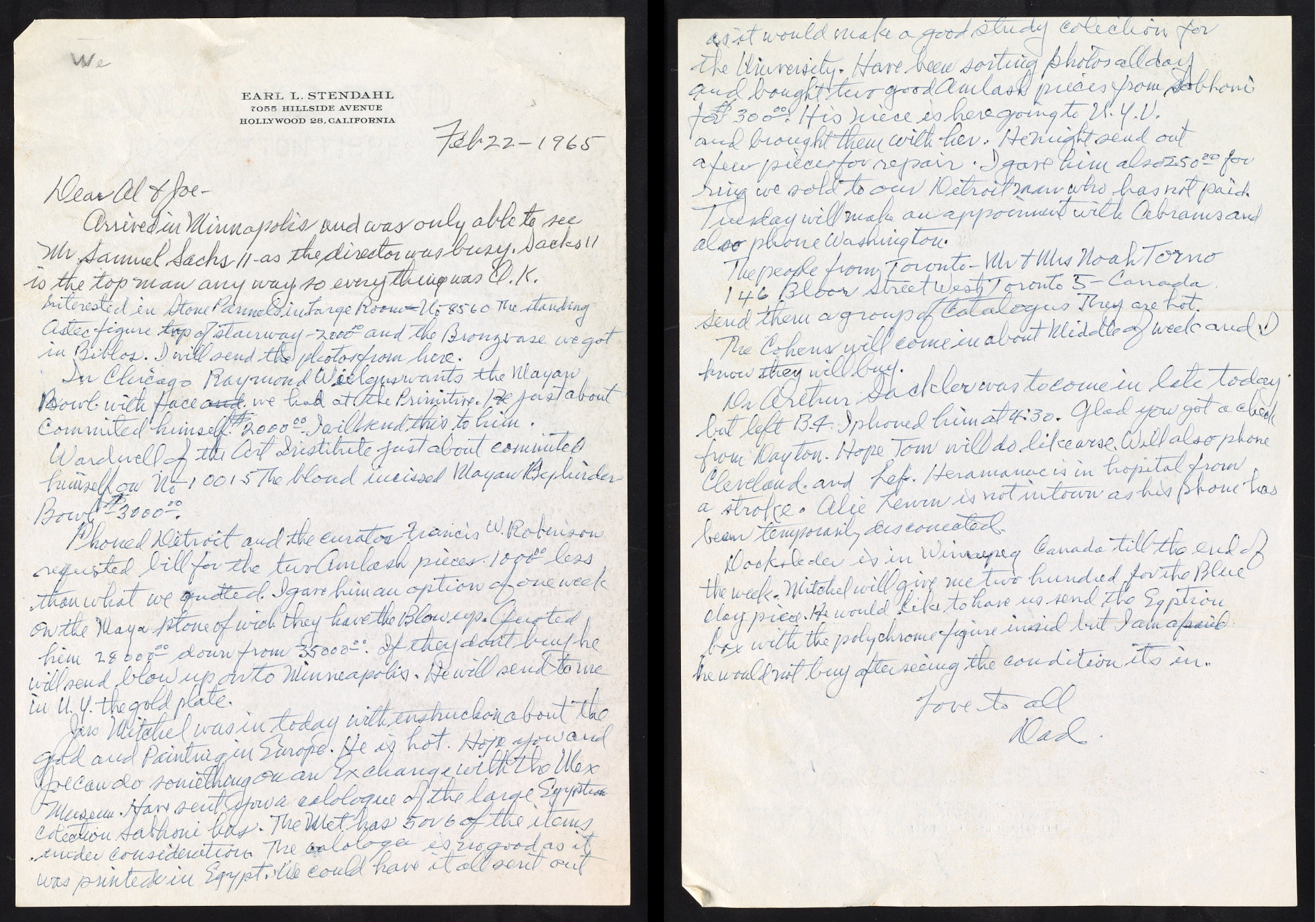

Earl Stendahl, from his travels to Los Angeles, to his son, Al Stendahl, and son-in-law, Joe Dammann, February 22, 1965

Dear Al & Joe –

Arrived in Minnapolis and was only able to see Mr. Samuel Sacks II-as the director was busy. Sacks II is the top man any way so everything was O.K. Interested in stone panels in Large Room – No-8560 the standing Astec figure top of stairway – 2000.00 and the Bronze vase we got in Biblos. I will send the photos from here.

In Chicago Raymond Wielgus wants the Mayan Bowl with face

andwe had at the Primitive. He just about committed himself $2000.00. I will send this to him. Wardwell of the Art Institute just about committed himself on No 10015 the blond incised Mayan Cylinder Bowl - $3000.00.

Phoned Detroit and the curator Francis W. Robinson requested bill for the two Amlash pieces 1000.00 less than what we quoted. I gave him an option of one week on the Maya stone of wich they have the blow up. Quoted him 28000.00 down from 35000.00. If they don’t buy he will send blow up on to Minneapolis. He will send to me in N.Y. the gold plate.

Jan Mitchel was in today with inshuckon about the gold and painting in Europe. He is hot. Hope you and Joe can do something on an exchange with the Mex Museum. . . . The people from Toronto – Mr. and Mrs. Noah Torno 146 Bloor Street West, Toronto 5 – Canada. Send them a group of catalogues. They are hot. The Cohens will come in about middle of week and I know they will buy. Mr. Arthur Sackler was to come in late today but left B.4. I phoned him at 4:30. Glad you got a check from Dayton. Hope Tom will do likewise. Will also phone Cleveland. and Leff. Heramanac is in hospital from a stroke.

. . . [Mitchell] would like to have us send the Egyptian box with the polychrome figure inside but I am afraid he would not buy after seeing the condition it’s in. Love to all Dad

A few months after his letter to Enid, in early 1965, Earl took a trip to Minneapolis, Chicago, Detroit, and then returned to New York. Business was booming, and the SAG was selling all sorts of antiquities.

In Minneapolis, Earl met with Samuel Sachs II (b. 1935), the deputy director, later to be director, at the Detroit Institute of Art (and then briefly at the Frick Collection), and was able to propose numerous sales. In Chicago, he visited more clientele: Raymond Wielgus (1920–2010), whose collection is now in the Eskenazi Museum at Indiana University, and the Art Institute of Chicago, where Alan Wardwell (1935–1999) was the first Curator of Primitive Art.17 In Detroit, Earl worked with curator Francis Robinson, selling Amlash works that the SAG purchased during the European tour. But the expensive object on offer in 1965 was a “Maya stone,” optioned for $35,000, then reduced to $28,000, which Earl indicated would be offered to Minnesota if Detroit took a pass. Detroit did pass; it is possible that the monument Earl referred to is Stela 2 from Piedras Negras, now at the Minneapolis Museum of Art.18

Back in New York, Jan Mitchell was considered “hot” by the SAG, which is to say “ready to spend money.” A paragraph below, Mr. and Mrs. Noah Torno of Toronto are also “hot,” and elsewhere in the letters and invoices, they are serious shoppers. The Cohens, Dr. Sackler, “Cleveland,” Jay Leff—Earl stayed on top of potential buyers, and by spelling them out in this letter, he reminded Al and Joe to do the same.

There was news for Earl to share as well: Another client Nasli Heeramaneck (1902–1971) had had a stroke. And then Earl waffled on shipping an object to a potential buyer, given its condition and worried that, if the client actually saw the work, the sale would fall through.

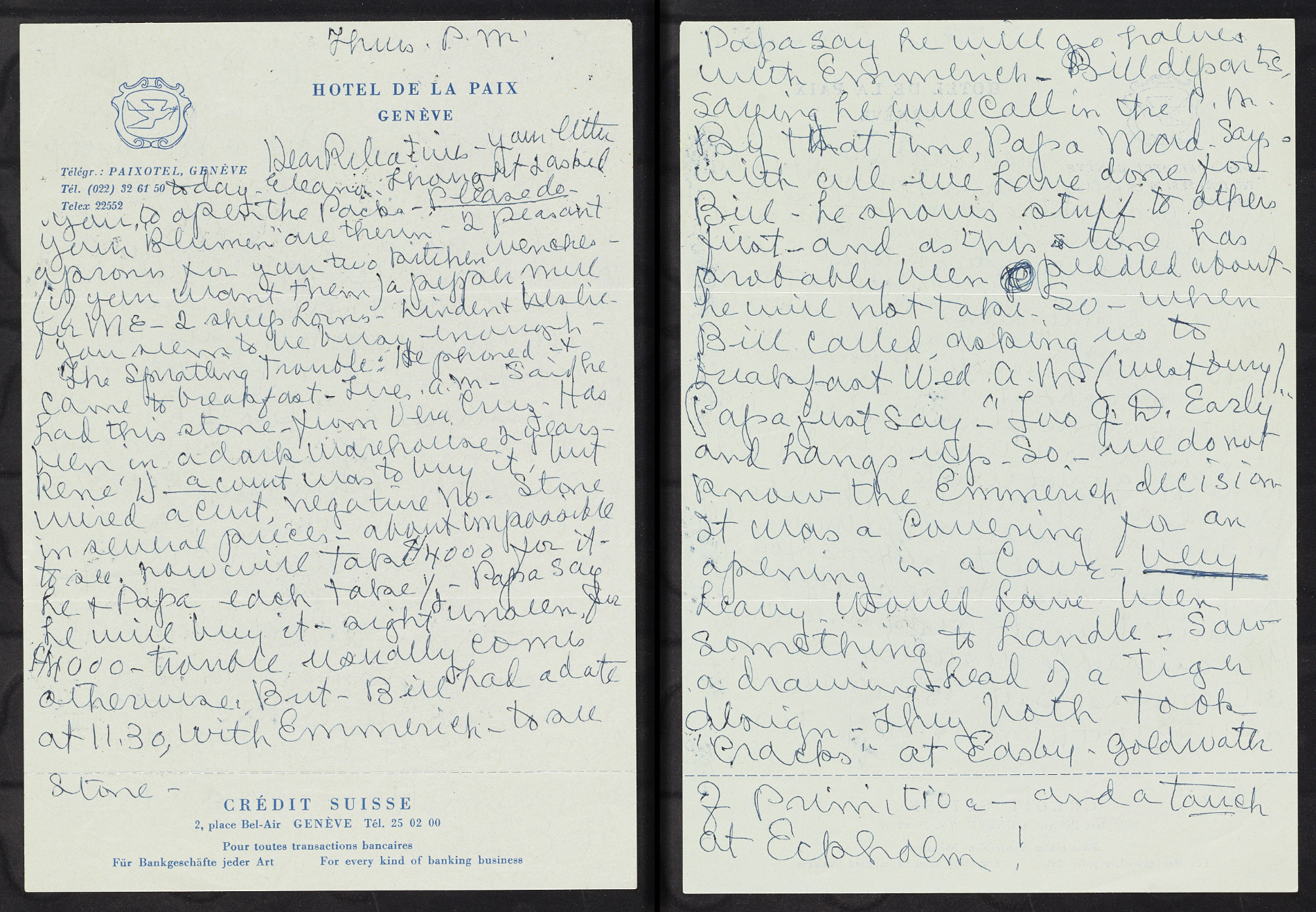

Enid, in New York, to the family, in Los Angeles, December 1965

Dear Relatives-

. . .

The Spratling Trouble: He phoned – & came to breakfast – Tue a.m. – Said he had this stone – from Vera Cruz. Has been in a dark warehouse 2 years – René D_ _a count was to buy it, but wired a curt, negative No. Stone in several pieces – about impossible to see. now will take $4000 for it – he & Papa each take 1⁄2 – Papa say he will buy it – sight unseen, for $4000 – trouble usually comes otherwise. But – Bill had a date at 11.30, with Emmerich – to see Stone-

Papa say he will go halves with Emmerich – Bill departs, saying he will call in the P.M. By that time, Papa Mad. Says with all we have done for Bill – he shows stuff to others first – and as this stone has probably been peddled about – he will not take. So – when Bill called, asking us to breakfast Wed. A.M. (Westbury) Papa just say – “Too G.D. Early” and hangs up – So – we do not know the Emmerich decision. It was a Covering for an opening in a Cave – very heavy. Would have been something to handle – Saw a drawing – head of a tiger design – They both took “cracks” at Easby – Goldwater of Primitive – and a touch at Eckholm!

From time to time, Enid’s letters—generally fewer in number—make astonishing revelations. In a letter written in December 1965, Enid recounted how Earl failed to close a deal with William Spratling (1900–1967).

As Matthew Robb and I have discussed elsewhere, this is the first known notice of Chalcatzingo Monument 9 in New York and the earliest specific attribution to William Spratling as the agent of its removal from Mexico to the United States.19 No other member of the Stendahl family made note of the aborted transaction with Spratling. Enid indicated that René d’Harnoncourt (1901–1968), director of the Museum of Modern Art and often consulted by Nelson Rockefeller, who founded the Museum of Primitive Art in 1957, turned it down with a “curt, negative, No.” From this letter it is difficult to determine whether $4,000 was the full price or half of the price; eventually gallerist André Emmerich (1924–2007) would sell the monument to the Munson-Williams-Proctor Museum of Art in Utica, New York, for $20,000. From other correspondence that Robb and I have consulted, it is clear there was some doubt about the work’s authenticity, and perhaps that is the source of the dig at the end of the letter, making fun of curator Elizabeth Easby, Robert Goldwater, director of the Museum of Primitive Art, and Gordon Ekholm, whose opinion the SAG was so often soliciting. Today Chalcatzingo 9 is back in the state of Morelos, having been repatriated to Mexico.

Conclusion

In this selection from the family letters, we see the arc of about a decade at the SAG. The SAG took an apartment in New York at the beginning of this period, so they were on the scene as prehispanic business developed there with Frances Pratt, Aaron Furman, and André Emmerich, noted in this selection of letters, and also when Eleanor Ward, Alphonse Jax, and Ed Merrin entered the trade. The Stendahls successfully conducted business with art museums nationwide, from Cleveland and Detroit to St. Louis, as well as sustaining relationships with private collectors, many of whom were building collections that would be foundational for museums. Robert Woods Bliss is the best-known of these collectors and Raymond and Laura Wielgus played an important role at the University of Indiana. By the time of Earl’s death, prehispanic art had permeated most US museums with encyclopedic aspirations, and encyclopedic aspirations were the rule of the 1960s and 1970s.20

The SAG successfully created a business with inventory that could be acquired for a few dollars or several thousand dollars. They launched exhibitions across the United States, particularly in southern California and often at colleges, but also at the Texas State Fair, and extensive catalogs document SAG offerings.21 They learned from collectors, museums, and other dealers, constantly adjusting to capture new business. In the letters cited here, Earl was very interested in Bliss’s plan to publish a lavish coffee table book of his collection, noting the handsome photographs and a $200,000 price tag and the uncertainty of pulling it off. This 1957 book inspired Earl to make plans with the publisher Harry N. Abrams for his own monumental book project, the 1968 Pre-Columbian Art of Mexico and Central America, a compendium of works sold by SAG over nearly thirty years, establishing new areas of study and organizational principles for the field. Earl died in 1966, before he could see the project come to fruition, but the plans were well under way. His son, Al, wrote the introduction and curator Hasso Von Winning wrote the text, an opportunity he might not have had without Earl’s death. This book quickly became an indispensable reference, and the publication catapulted Von Winning from a little-known researcher in Los Angeles into a national figure.

The Stendahls, too, became national and international figures. At the beginning of the decade addressed in this suite of letters, they had a substantial number of regional clients, especially from the motion picture industry, as well as key national collectors such as Bliss and Rockefeller, but during this decade they expanded their clientele dramatically, building greater resilience into their business model. But letters from 1963 onward address a new side of the business, in which monumental works of stone were being stolen from Mexico and Guatemala. Sales of works such as Piedras Negras Stela 2 or Chalcatzingo Monument 9—and the attendant high prices and their visibility—would attract international attention of archaeologists and national governments alike. The Stendahl Art Galleries would not see the picture emerging for many years, but the 1970 United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)’s Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Export, Import and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property as well as the 1972 bilateral agreement between Mexico and the United States would mark the beginning of the end for the SAG. The family letters were filed away, carefully preserved historical documents that today yield exquisite details of a unique Los Angeles business.

I would like to thank the PHAPI team, Megan O’Neil and Matthew Robb, Kim Richter, and April Dammann.

Notes

For her book, Exhibitionist: Earl Stendahl, Art Dealer as Impresario (Angel City Press, 2011), April Dammann did not consult the family letters. Megan O’Neil and I consulted the family letters extensively for our article, “Stendahl Art Galleries in Europe: Expanding the Market for Pre-Hispanic at Mid-Century,” Journal for Art Market Studies 7, no. 1 (2023), https://www.fokum-jams.org/index.php/jams.

-

Pál Kelemen’s 1943 Medieval American Art featured many works from the Brummer Gallery, and several of these objects would pass through Stendahl Art Galleries (SAG). Both Michael Coe’s 1966 books, Mexico and The Maya, included SAG objects, as did George Kubler’s 1962 and 1975 editions of The Art and Architecture of Ancient America: The Mexican, Maya, and Andean Peoples. Not only did I follow these pioneers in my own work, but many of the designations, from “Nayarit” style to “Remojadas,” devolve from market practices established by the SAG. ↩︎

-

Stendahl Art Galleries records, circa 1880–2003, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no. 2017.M.38, box 105 (henceforth, SAG records). The family letters were scanned in early 2020, at the beginning of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Staff members across the GRI signed up to transcribe the family letters using the Zooniverse crowdsourcing program. The handwriting of the letters (they are rarely typed) is difficult to decipher, and the spelling is erratic and nonstandard, making transcription difficult. Using the Zooniverse transcription as a basis, Getty staff have begun the process of confirming transcriptions and assigning identities to individuals named in the letters. Few letters bear full dates, and most are indicated only by “Thursday” or “March 3,” but the transcription team has nevertheless been able to anchor most dates. I am grateful to the Stendahl/Dammann family for their careful retention of nearly eighty years of records and their generous donation of these records to the GRI. ↩︎

-

PHAPI staff and advisers, including Andrew Turner, Payton Phillips Quintanilla, Alicia Houtrouw, Kylie King, Megan O’Neil, Matthew Robb, Michael Mathliewitz, and Henna Khanom, have analyzed the data and contents of the archive since 2019. ↩︎

-

Guillermo Echániz Correspondence, SAG records, accessed September 9, 2023, https://getty.libguides.com/Stendahl/Echaniz. ↩︎

-

Al to Earl, 1957, SAG records. ↩︎

-

For more on Stendahl’s biography, see Dammann, Exhibitionist. ↩︎

-

O’Neil and Miller, “Stendahl Art Galleries in Europe.” ↩︎

-

Peterson’s work is little known and less studied today. Frederick A. Peterson Papers, 1701–1977 (bulk 1950–1977), University of New Mexico Center for Southwest Research & Special Collections, MSS-518-BC, https://nmarchives.unm.edu/repositories/22/resources/1696. ↩︎

-

Michael Coe and Stephen Houston, “How to Identify Real Fakes: A User’s Guide to Mayan ‘Codices,’” Maya Decipherment, December 12, 2017, http s://mayadecipherment.com/2017/12/12/how-to-identify-real-fakes-a-users-guide-to-mayan-codices/. ↩︎

-

Dammann, Exhibitionist, 140–42. ↩︎

-

N. C. Christopher Couch, Pre-Columbian Art from the Ernest Erickson Collection at the American Museum of Natural History (The Museum, 1988). ↩︎

-

Some Kennedy works are in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) collections today. La Mar Stela 3, which he owned and which had been on long-term loan to LACMA, was returned to Mexico in 2021. ↩︎

-

This urn was published in Pre-Columbian Art of Mexico and Central America by Hasso Von Winning in 1968 (fig. 238). Adam Sellen drew it (KAISER 1), and it may be seen online in the “Catalogue of Zapotec Effigy Vessels,” FAMSI Recursos, 2005, http://research.famsi.org/spanish/zapotec/zapotec_list_es.php?search=glifo C&title=Vasijas Efigie Zapotecas&tab=zapotec. ↩︎

-

Rita Reif, “Antiques: A Treasure Goes Public,” The New York Times, March 8, 1987, Section 2, p. 37. ↩︎

-

The collections of the Museum of the American Indian formed the foundational collections of the National Museum of the American Indian in 1987. Maria Galban, “Searching Heye and Low: Reconstructing MAI Collections Histories Through Documentation,” paper delivered at “Collecting Mesoamerican Art in the Twentieth Century: Revealing Histories of the International Art Market,” at the Getty Center, April 26, 2024. ↩︎

-

Mitchell made a major collection from various dealers. See Julie Jones, ed., The Art of Precolumbian Gold: The Jan Mitchell Collection (Little, Brown, and Co., 1985). ↩︎

-

Earl only mentioned Raymond Wielgus, but he built the collection with his wife, Laura. “Raymond J. Wielgus,” University Honors & Awards, accessed September 10, 2024, https://honorsandawards.iu.edu/awards/honoree/1037.html. The work that Earl described may be 73.10.2 or 73.10.3 at the Eskenazi Museum. ↩︎

-

Stela Fragment, c. 800, Maya, limestone, 76½ × 24 × 2¼ in. Minneapolis Institute of Art: Gift of the Morse Foundation, 66.10. ↩︎

-

Mary E. Miller and Matthew Robb, “Spratling Troubles,” paper delivered at “Collecting Mesoamerican Art in the Twentieth Century: Revealing Histories of the International Art Market,” at the Getty Center, April 26, 2024. ↩︎

-

Mary E Miller, “A Historiographic Afterword,” in The Encyclopedic Museum, ed. Donatien Grau (Getty 2019), 230–41. ↩︎

-

There were many different catalogs; one of the most comprehensive is Pre-Columbian Art: A Loan Exhibition of Objects Illustrating the Cultures of Middle American Civilizations Before Their Conquest by Cortez (The Museum [Dallas], 1950). ↩︎