“Tomorrow I must see you—somewhere where we can be alone. . . .”

“There’s the Art Museum—in the Park,” he explained, as she looked puzzled. . . .

Avoiding the popular “Wolfe collection,” whose anecdotic canvases filled one of the main galleries of the queer wilderness of cast-iron and encaustic tiles known as the Metropolitan Museum, they had wandered down a passage to the room where the “Cesnola antiquities” mouldered in unvisited loneliness.

They had this melancholy retreat to themselves, and seated on the divan enclosing the central steam-radiator, they were staring silently at the glass cabinets mounted in ebonized wood. . . .

“It’s odd,” Madame Olenska said, “I never came here before.”

“Ah well—. Some day, I suppose, it will be a great Museum.”

Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

With the return of peace after the dislocations of the US Civil War, The Metropolitan Museum of Art was founded in 1870 by businessmen, civic leaders, and artists in New York. Unlike its European counterparts, the institution had no royal collections on which to build and no dedicated space. Yet the founders had noble, and ambitious, intentions: The Met was to represent the world’s art history—of all periods and all places. In 1880, the museum opened to the public at its current site at 82nd Street and Fifth Avenue. The scene described by Edith Wharton in her 1920 novel should be imagined as being set shortly after this. Positioned on the edge of Central Park, the museum was linked with other currents of improvement in New York, including the park itself (fig. 1). The museum grew quickly, as vastly increased wealth of the economic elite in the city was translated into rapidly expanding art collections, both private and public.

Nearly two thousand works of pre-Columbian art were acquired as gifts and purchases by 1900, including gifts from the Hudson River School painter Frederic Church, a trustee of the museum and an enthusiastic early supporter of ancient American art, and the purchase of a collection of Mexican antiquities (and pseudo antiquities) from Luigi Petich, an Italian diplomat.1 Hailed in the nineteenth century as American antiquities for an American museum, the pre-Columbian collection was seen as essential to the young and still inchoate organization establishing its institutional identity.2 Yet this interest waxed and waned, only to wax again by the last quarter of the twentieth century.

After a brief overview of The Met’s early presentation of ancient American art and its subsequent reversal—the half century in which the museum largely turned away from the field—this essay addresses The Met’s later embrace of the arts of ancient Latin America. The Met eventually returned to the field in the belated wake of modernism, most impactfully via Nelson A. Rockefeller and the 1969 transfer of the collections of the Museum of Primitive Art to The Met. This essay focuses largely on the period after 1914 and before 1969—a time when The Met’s ambivalence about the place of ancient American art within its walls reveals changing conceptions about what constitutes the history of art and the place of ancient American civilizations in world history.

Ancient American Art at The Met at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

The collection of “American antiquities” was initially displayed in the basement hall of The Met’s first Central Park building, alongside arms and armor and the collection of casts and other reproductions, including photographs and copies of Maya murals created by photographer-explorers Désiré Charnay and Augustus Le Plongeon.3 After the museum’s expansion in 1888 (see figure 1), the pre-Columbian collection, which was to increase substantially in the next decade, was moved upstairs, adjacent to the paintings galleries and, later, musical instruments (fig. 2).4 In the late nineteenth century, the museum visiting experience was often a cold and dark one: The large gallery initially was lit only by skylights—the museum was not yet electrified—and dependent on inadequate steam heat. The sizeable number of objects from the permanent collection was augmented by loans on occasion, and the works were carefully mounted and laid out by type (fig. 3).5 As John Taylor Johnson and Louis P. di Cesnola, the museum’s first president and director, respectively, wrote in 1882, appealing to the museum’s membership to establish a department of “old American art”: “The history of the ancient American civilizations can and will be recovered and read if we gather and arrange in order their works of art.”6

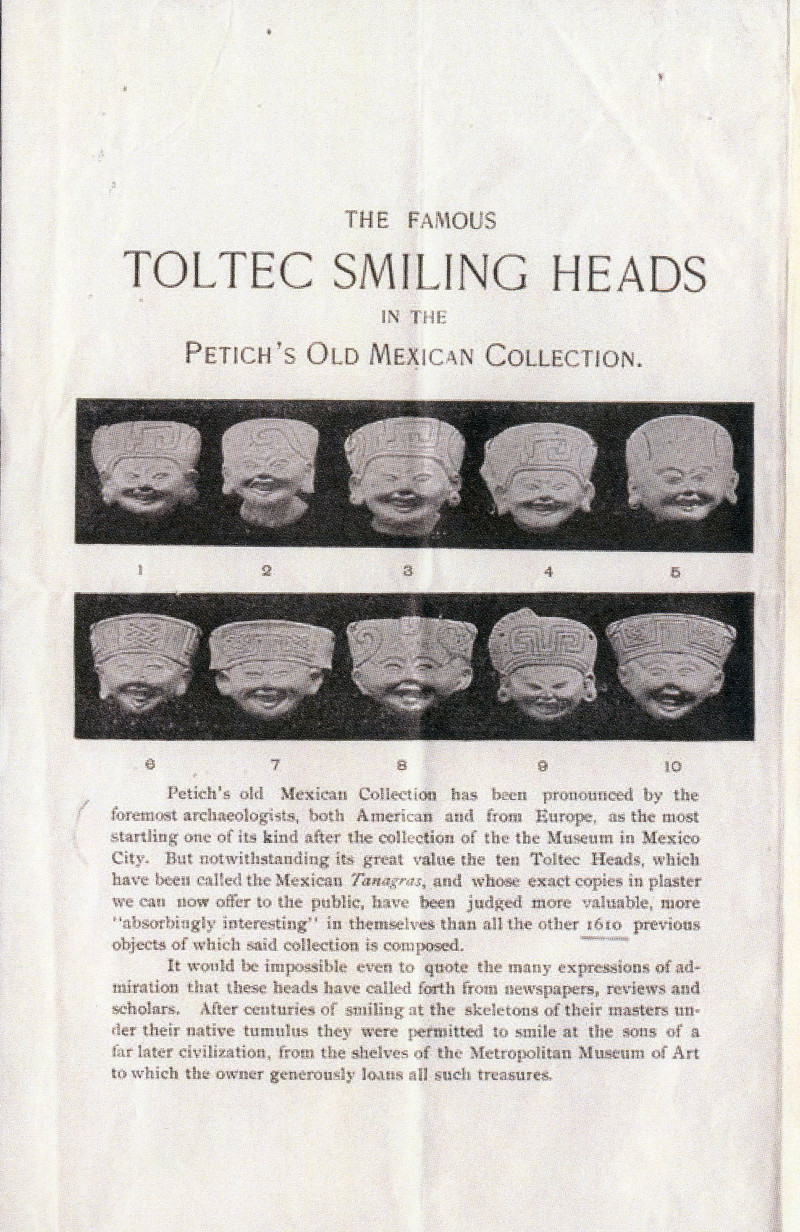

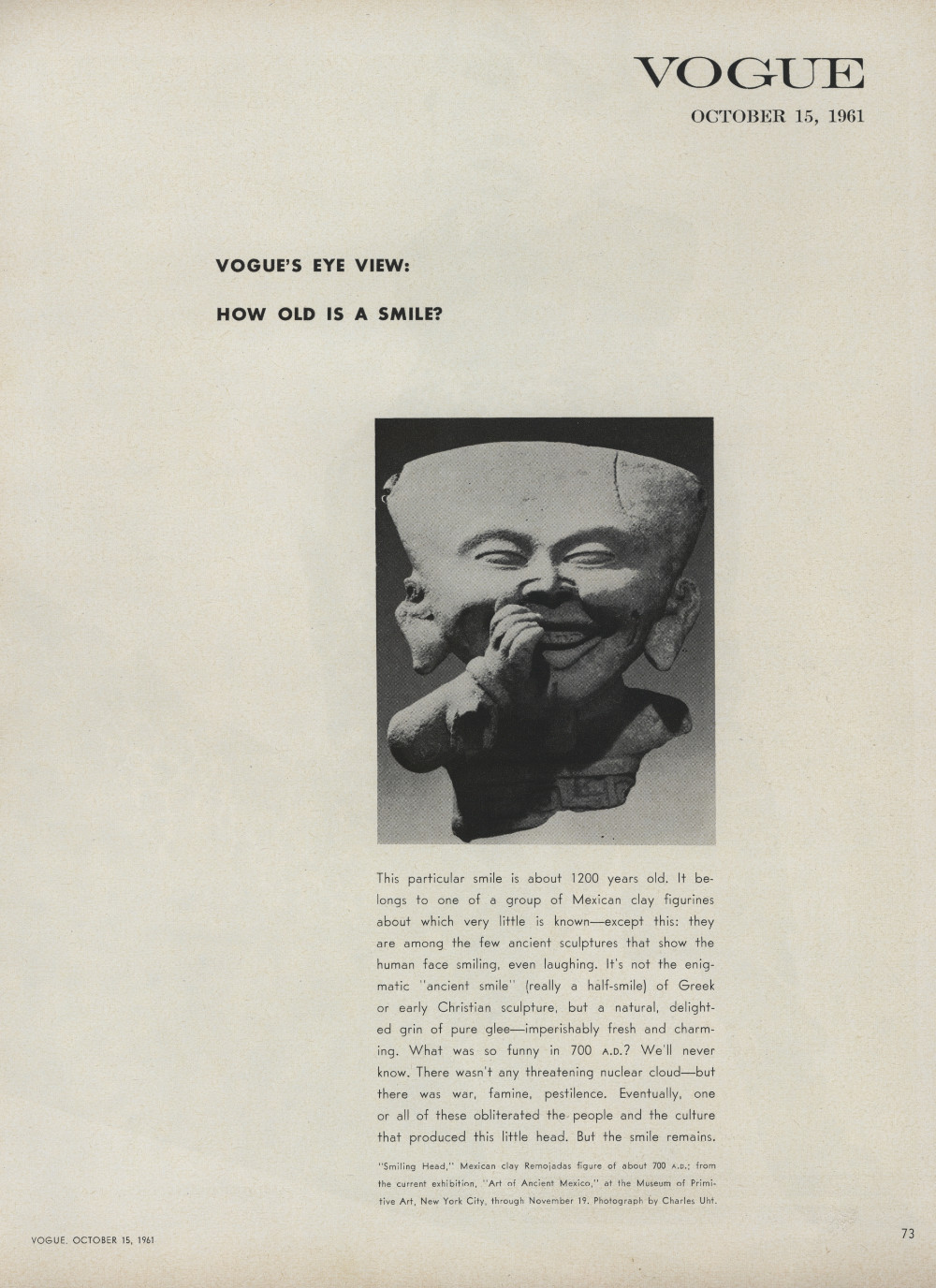

Assessments of the ancient American art at the time were often quite positive. The guidebook to the museum’s collections notes that “the accounts of the Spanish Conquerors as to the high civilization of the old Peruvians find abundant corroboration in these remains.”7 The stars of the collection were what were then called “Toltec Smiling Faces,” a type of sculpture that was largely unknown until that time (figs. 4 and 5).8 Made in Veracruz in the seventh or eighth century in a style now called Remojadas, these enigmatic figures would go on to capture visitors’ imaginations for over a century.

Despite the initial interest in ancient American art, the museum began to reconsider it in the second decade of the twentieth century, as new leadership at the museum questioned whether such objects belonged in an art museum.9 In 1914, most of the ancient American works were sent across Central Park to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), losing their designation as “art” as part of that transition. Some works, especially items of gold or silver, were retained a bit longer, but those, too, were eventually sent on long-term loan, this time to the Brooklyn Museum.10 The art of ancient Latin America would go on to have only a spectral presence at The Met for the next half century.11

There were some interesting exceptions to the mass relegation of ancient American objects to other institutions, however. Some twenty Maya and Mixtec items collected by the businessman and philanthropist Heber R. Bishop remained in the museum along with the Asian jades that formed the bulk of his collection. Indeed, a reproduction of a Mixtec figurine in that collection was reportedly one of the most popular items in the museum’s book shop in the 1950s.12 Ancient Peruvian textiles, which The Met began to collect as early as 1882, not only remained in the museum but continued to be collected, at least sporadically. Following the model of London’s South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), The Met adopted a similar guiding principle that museums could positively influence industrial design. The garment business was New York’s largest industry; the creation of The Met’s Textile Study Room in 1910 was fueled by the idea that the study of the decorative arts would lead to better design in factories and workshops (fig. 6).

The textile collection grew over the years, eventually becoming the subject of a special exhibition in 1931, complete with a catalog intended primarily for “students of ornament,” a reminder of the abiding influence of Owen Jones, the nineteenth-century architect, designer, and theorist, whose sourcebook The Grammar of Ornament (1856) was intended to make design principles in the decorative arts, viewed globally, more widely available.13 By the 1950s, however, textiles were collected not simply for study purposes but as works of art in their own right. As modern art became more widely embraced, the path was laid for seeing ancient Andean textiles in a new way. In 1959, John Phillips, a curator in the Department of Renaissance and Post-Renaissance Art who had worked on the 1931 exhibition, recommended the purchase of eight Peruvian textiles. Perhaps signaling a changing attitude at the museum, Phillips noted, “In our day, when highly conventionalized forms have become familiar through the agency of contemporary painting and sculpture, these textiles seem far less outré than they once did.”14

It should be noted, however, that The Met was hardly an early adopter of what we now think of as modern art. Indeed, it is important to bear in mind that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) was born in part out of frustrations with The Met’s obdurate refusal to entertain contemporary art. Later in the century, it would be MoMA, and its neighbor the Museum of Primitive Art, that would mount important exhibitions of ancient American art. One interesting aspect of this change was that The Met’s move was strikingly at odds with some broader currents in the United States at the time. While The Met remained quiet for decades, other institutions, including the Brooklyn Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and even the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, were doubling down on collecting and exhibiting pre-Columbian art, if only, as was the case with the National Gallery, for a limited time.15

By 1952, leadership at The Met began to think that perhaps it had been a mistake to relegate its pre-Columbian collection to other institutions.16 The museum began to reenter the field largely through the efforts of Dudley Easby Jr., who joined The Met after World War II. He had previously worked with Nelson A. Rockefeller in the Office of Inter-American Affairs, the US governmental agency promoting hemispheric solidarity during the 1940s to counter German and Italian propaganda in Latin America.17 From his post as the museum’s General Counsel, Easby was a tireless advocate for the return of ancient American art to The Met. At the invitation of the museum, Elizabeth Easby—Dudley’s wife and a noted scholar of ancient American art—prepared a report of The Met’s holdings of pre-Columbian art, “forgotten treasures” that by now had long been on loan to the AMNH and the Brooklyn Museum and featured in exhibitions and publications internationally.18

The return of ancient American art to The Met progressed in fits and starts, however. In 1954, the museum hosted an exhibition of pre-Columbian gold organized by Dudley and Elizabeth Easby, an exhibition also shown in Washington and San Francisco (fig. 7).19 A gallery dedicated to “pre-Columbian” art was first suggested in 1956, but in that same year, Easby noted emphatically in correspondence that the museum was not exhibiting pre-Columbian art and that it did not have plans to do so in the future, perhaps in light of the imminent opening of the Museum of Primitive Art (see below).20 Yet, by 1962, the tide had definitively turned. With the support of James Rorimer, the director, Easby orchestrated the return of the Brooklyn loans and initiated a campaign of acquisitions.21 These included select purchases of monumental stone works, textiles, and the cultivation of specific collectors, such as Nathan Cummings, who eventually divided his collection of Peruvian ceramics between the Art Institute of Chicago and The Met. A selection of works from his collection was shown at The Met from 1964 until 1969 (fig. 8).22 These works were nominally cared for by the American Wing at this time, in what a curator in that department described as a “weird marriage of American decorative arts with pre-Columbian art.”23 The ancient American collection became a source of contention within the museum, as American Wing curators were increasingly resentful of having to accommodate hundreds of new works over which they had no say.

Easby and Rorimer persisted, however. Beginning in 1966, they persuaded Alice K. Bache to donate a significant portion of her collection of ancient American art. Trained as a sculptor and painter in New Orleans before moving to New York to study philosophy, Bache stands out against the sea of male collectors and other women who collected in conjunction with spouses or other family members. She worked closely with archaeologists at the AMNH, including Junius Bird and Gordon Ekholm, who advised her on purchases. She gave and bequeathed numerous works to the AMNH and the Museum of the American Indian (now the National Museum of the American Indian), but she reserved the most important objects for The Met. Primarily works of art in gold, the Bache gifts were transformative for the collection. Indeed, the fine quality of the works surely paved the way for the museum’s trustees to consider returning to the field in earnest. At this point, plans were underway for a permanent gallery for ancient American art.24

These plans were vastly expanded in 1969, however, when the museum agreed to accept Nelson A. Rockefeller’s collection, which included ancient American, Native American, African, and Oceanic art—a grouping of disparate traditions by then referred to under the rubric of “primitive art.” Appointed a trustee of The Met in 1930, Rockefeller tried repeatedly over the years to entice the museum to return to the field of ancient American art. In 1939, he proposed that The Met join with the AMNH to support archaeological expeditions in Latin America to collect primitive art, a plan thwarted by Herbert Winlock, The Met’s director at the time and an Egyptologist determined not to let new interests distract the museum from building up the Egyptian collection.25 Continually rebuffed by The Met, Rockefeller turned to MoMA, offering to establish a department of primitive art there in 1942.26 But Alfred H. Barr Jr., MoMA’s founding director, while happy to host exhibitions of other-than-Western art, was adamant that MoMA refrain from collecting in this area.27 With his plans rejected by both The Met and MoMA, Rockefeller decided to create his own museum, following in the footsteps of his mother, who, in similar circumstances, helped found MoMA when The Met refused to collect or exhibit contemporary art.

The Museum of Primitive Art

Rockefeller began planning the new institution dedicated to the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Indigenous Americas in the late 1940s with the assistance and advice of René d’Harnoncourt, who would later become the director of MoMA. The Museum of Primitive Art (MPA), as it became known, opened to the public in 1957 in a Beaux-Arts townhouse adjacent to Rockefeller’s boyhood home on 54th Street, directly across the street from MoMA (fig. 9). There was a clear synergy between MoMA and the MPA, not surprising given that the two museums shared governance, projects, and support from the Rockefeller family. The gray stone facade was left unchanged, but the interiors were converted into simple, minimalist spaces. Still smarting from The Met’s decision decades earlier to exclude pre-Columbian art from its holdings, Rockefeller was deliberate in defining the purview of the MPA as “the important art forms not included in The Met’s cognizance of the past.”28

The MPA’s foundation documents, prepared in 1954, stress that the MPA’s acquisitions and exhibitions would be limited to objects of artistic excellence and would in no way attempt to be representative in terms of anthropology.29 Works were to be presented as fine art, displayed in a manner that was resolutely modern. Most works were on open display—not in cases—a decision that, while aesthetically striking, proved problematic at times (see below). In the foundation documents, the institution is called the Museum of Indigenous Art, but by the time the museum opened three years later it had become the Museum of Primitive Art. Rockefeller only reluctantly changed the name—his Mexican friends did not like the new name at all—but “Indigenous” apparently created confusion. In one account, Rockefeller noted that the institution got mixed up with a new museum of contemporary craft; elsewhere he recalled that people confused “Indigenous” with “indigent.”30

D’Harnoncourt was deeply influenced by a starkly modernist installation of a 1935 MoMA exhibition on African art initiated by Barr and organized by James Johnson Sweeney (see Koontz, this volume). The exhibition was one of a series of what Barr called “primitive” exhibitions at MoMA, encompassing American Sources of Modern Art in 1933 (fig. 10)—which included works from The Met’s collection—as well as Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art in 1940 and Ancient Art of the Andes in 1954. Robert Goldwater, a noted historian of modern art with a strong interest in African sculpture, had also worked on the 1935 African exhibition (fig. 11). Brought in to be the first director of the MPA, Goldwater expanded his concept of “affinity” for gallery installations: Objects should be grouped by visual form, not necessarily by subject matter or locale. Goldwater was unapologetic about the decontextualization of works in the MPA installations: “To put any of the world’s art in a museum is to take it out of its intended environment.” No matter the source, works possess inherent qualities “of skill, of design, of expressive form and concentrated emotion that make it art”—that render it accessible.31 The goal was to make the installations inviting and relevant to modern tastes and interests.

The MPA exhibitions, all relatively small in comparison with those at MoMA, were similarly minimalist in character, with limited didactic information. The exhibitions were minimalist in security matters as well. Perhaps not surprisingly, a small Olmec figure went missing at the time of the first exhibition (fig. 12). The paperwork surrounding the theft is fascinating. The letter from Goldwater to Rockefeller apprising him of the incident described the theft as likely the work of a “crackpot” who left a note with the words “American degenerate religious figure,” conjuring the specter of idolatry.32 The initial security report, however, says something slightly different. The note had been placed next to the gallery’s thermostat, and in a label-like format said, “AMERICAN, DECADENT, probully [sic] of religious significance,” echoing the label of the Olmec figure. It seems like an almost Dada-esque joke on the pretensions of museum displays of other-than-Western art.33

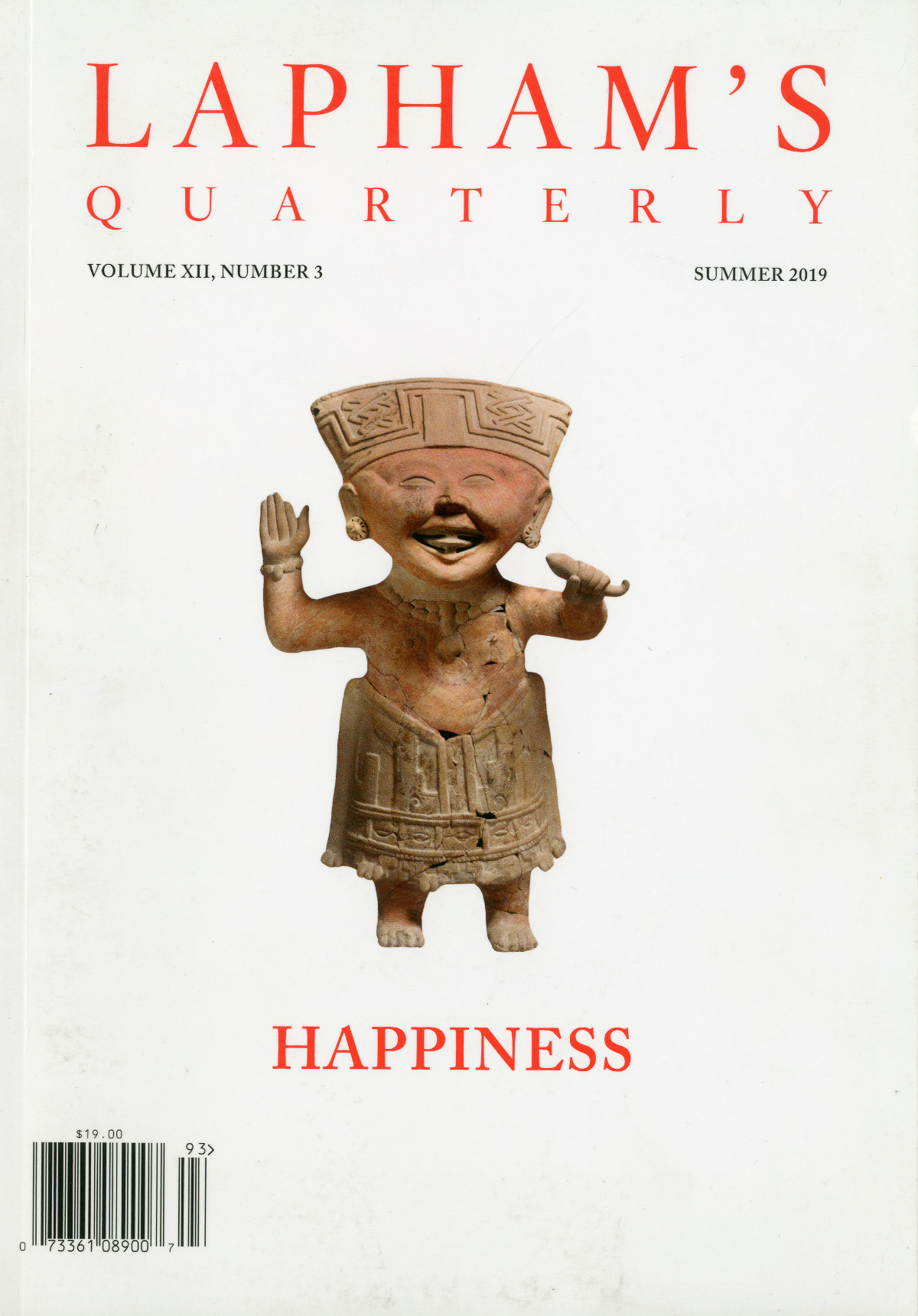

Although admittedly small—attendance at the MPA in 1964, one of its peak years, was 18,365, while its neighbor across the street received one million in the same year—it was influential, and for the most part it enjoyed great critical success.34 The Art of Ancient Mexico exhibition in 1961, for example, was reviewed widely and enjoyed a spot on the Today show on broadcast television. The New York Times described the aesthetic value of the works “demonstrably great,” while still holding on to ideas that these civilizations were “baffling” and “mysterious.”35 Remojadas sculptures, with what many took to be their seemingly overt expression of joy—a rarity in ancient American art—continued to be favored in media oriented to the general public (fig. 13).

The staff of the MPA, and Rockefeller himself, paid great attention to design, from installations to invitations. The publications in the early years were essentially elegant checklists; it is only later that the exhibitions were accompanied by serious scholarly contributions. Julie Jones, the MPA’s first (and only) full-time curator for the arts of the ancient Americas, produced The Art of Empire: The Inca of Peru (1963); later, working with Yale anthropologist Michael D. Coe, the museum published The Jaguar’s Children: Pre-Classic Central Mexico (1965). These exhibitions were also the two most-attended ancient American shows at the MPA.36 About half of the exhibitions at the MPA included works from at least two, or usually all three, areas represented by the museum. Of the single-area shows, a little over a third of the exhibitions were dedicated to the arts of the ancient Americas. In the later years, the idea was to have one show from each area per year.

In the end, the MPA was open for seventeen years, during which time the staff mounted some seventy exhibitions and published nearly sixty books, catalogs, and gallery guides. By the late 1960s, however, the future of the MPA was in doubt. Rockefeller’s son Michael, whom he had hoped would take over as director, was lost on a collecting expedition in 1961. Some four months after Michael’s death, d’Harnoncourt wrote to Rockefeller about the future of the MPA, including questioning who would be its director when Goldwater retired.37 Some scholars have suggested that Rockefeller wanted to close the MPA for financial reasons, and indeed, parts of the collection were put up at auction in 1967, ten years after the museum had opened.38 The African works fetched robust prices, but many of the ancient American works sold for well less than their initial purchase price.39 While Rockefeller had hoped the MPA would become more self-sustaining financially, money was not the impetus for the dissolution of the institution.

Other factors influenced Rockefeller’s thinking. In 1966, he was running for a third term as governor of New York, and he was increasingly seen as too rich and too removed from the average New Yorker. The optics of art collecting surely did not help in the opinion polls. Public opinion about collecting archaeological material was also beginning to shift in the mid-sixties, and this surely had a significant impact on Rockefeller’s decision. The MPA received a letter in May of 1966 informing them that the Department of State had received a diplomatic note from the Guatemalan embassy regarding the return of Piedras Negras Stela 5, a work purchased from a New York gallery in 1963.40 The subject of the art market’s relationship to the destruction of archaeological sites was becoming an increasingly important topic of public debate, and it undoubtedly had an impact on Rockefeller’s impulse to collect antiquities from Latin America, especially in light of what he considered to be his very close relationship with that region of the world.41

Moving Uptown

The reasons for MPA’s closure were ultimately overdetermined.42 Whatever the reason, or reasons, by the mid-1960s, it was clear to the staff that Rockefeller had run out of enthusiasm.43 In the spring of 1967, d’Harnoncourt, Rockefeller, and Thomas Hoving, who became director of The Met in April of that year, gathered at Rockefeller’s Fifth Avenue apartment to discuss a transfer of the MPA to The Met.44 This was a moment when The Met, led by an energetic new director, was embarking on a massive expansion, including the construction of new wings to house the Temple of Dendur and the Lehman Collection. The proposed Rockefeller Wing would become the final major expansion. Although The Met had been cautiously reentering the field of ancient American art under the previous two directors, Francis Taylor and James Rorimer, Hoving made the decisive move, and on a grand scale.

The agreement was signed in 1969, and the announcement of the transfer was made at a preview of an exhibition of some one thousand works from the MPA that year (fig. 14). A considerable critical and popular success, the exhibition received over 170,000 visitors: about half the number the MPA received during its lifetime.45 Accompanied by a catalog and a Bulletin—the cover graced by a Remojadas figure—the exhibition was one of three celebrating Rockefeller’s gifts of art to major institutions, including MoMA.46 Rockefeller had finally triumphed at The Met, some forty years after he first attempted to persuade the museum to return to the field of ancient American art. In the following year, the MPA celebrated The Met’s own collection of ancient American art—a collection almost completely ignored by the uptown institution for over half a century (fig. 15).

Easby stepped down as The Met’s General Counsel to become chair of the newly formed department in 1969. Already in ill health, however, his retirement from that post (“on or before January 1, 1971”) was agreed upon by Rockefeller and The Met in August of 1969.47 Goldwater and Douglas Newton, an MPA curator who was to become chair of the new department at The Met, moved uptown shortly after the transfer was announced in 1969. The MPA closed in 1974, and the remaining staff—including Julie Jones—library, and collections also moved uptown.48 Of the 1,731 of works of African, Oceanic, and ancient American art that were accessioned by The Met in 1979 (the year Rockefeller died), nearly one thousand were from the Americas—largely, but not exclusively, of the pre-Columbian era.

By the time the MPA moved uptown, however, The Met had been engaging with ancient American art for nearly a decade. With the help of Elizabeth Easby, a consultant at The Met for the Nathan Cummings exhibition in 1964 and acting curator at the Brooklyn Museum between 1965 and 1968, the museum organized several small exhibitions in the 1960s, as well as Before Cortés: Sculpture of Middle America, an ambitious project that included some three hundred works and was seen by over three hundred thousand visitors (fig. 16). The exhibition was part of a recent agreement between the museum and Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia to exchange loans, the beginning of the museum’s attempt to reckon with the growing concerns about how the art market’s demand for antiquities was destroying archaeological sites in Latin America.49

The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, named in memory of Nelson’s son, opened on January 19, 1982, three years after Nelson himself died. Nearly half a million people visited the wing in its first year, and critical reception was largely positive.50 Covering some forty thousand square feet on the museum’s south side, the wing mirrored the glass enclosure of the Temple of Dendur on the museum’s north side. The inaugural installation drew from the spare installation style of the MPA, albeit with more works behind glass (fig. 17). The theatrical lighting, however, was perhaps the most striking feature of the new galleries. Finished in a uniform beige, the galleries had little ambient light, making the spotlights on sculpture quite dramatic (fig. 18). Julie Jones became the first fulltime curator of this field at The Met, a post she continued to hold for almost forty years.

Ancient American Art at The Met: The First Hundred Years

Although we often slide past this fact, most museum collections are formed more through start-and-stop processes rather than slow-and-steady ones. But, even if we recognize that, the history of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s engagement with the arts of the ancient Americas is marked, perhaps more than most, by periods of enthusiastic embrace followed by stunning rejections. Initially celebrated as American antiquities for an American museum in the nineteenth century, only to be largely expelled from the institution for much of the twentieth, pre-Columbian art returned to The Met as modern in the 1960s.51 The Met’s decision to reenter this field in the 1960s was ultimately driven by multiple factors, including currents in contemporary art and broader social issues, reminding us of the complex interplay between specific individuals, institutions, and shifting ideas about what is appropriate for an American art museum.

As we embark on the first major renovation of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing in its forty-three-year history, my cocurator, Laura Filloy Nadal, and I, along with our team, continue to wrestle with this legacy. The place of works created in the Americas prior to the European invasion within museums continues to be the subject of debate. At the heart of these debates is the question of what art is—in many ways, a question that has been asked over the entire course of The Met’s history. Do these objects belong in an art museum, and if so, where? Increasingly, the debate centers on whether these collections even belong in a museum, outside of the lands in which they were made, a question that must also be framed by a recognition of the rich constellations of cultural heritage represented in New York’s social fabric. The Met’s own history of ancient American art initially in, then out, and then in again, as disconcerting as the history is at times, should also serve as a reminder that museums are living, evolving institutions, and that this capacity for change should give us hope (fig. 19).

I thank Victoria Lyall and Ellen Hoobler for the kind invitation to participate in this volume and for their insightful comments on an earlier version of this essay. This research would not be possible without the help of many archivists and colleagues. At The Met Archive, this includes Jim Moske, Melissa Bell, and Sarah Rappo, and Stephanie Post in the Digital Department. In The Met’s Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, I thank Matthew Noiseux and Paige Silva for their help with the archives of the Museum of Primitive Art. I am grateful to Natalie DeJesus, formerly of The Met, for research assistance. I owe particular thanks to Jack Meyers, president of the Rockefeller Archive Center, and his staff, especially Michele Hiltzik Beckerman, Assistant Director for Reference at the Center. Kelly Schulz, Archivist, National Gallery of Art Archives, and Jennifer Jolly, Ithaca College, were very helpful with my questions about Dudley and Elizabeth Easby. Steve Odenheimer was generous in sharing information about his aunt, Alice K. Bache. Alicia Boswell, Ellen Hoobler, Rex Koontz, Victoria Lyall, Mary Miller, Megan O’Neil, Matthew Robb, and Andrew Turner have all kindly shared documents and ideas over the years, for which I am very grateful. Most of all, I am in debt to Ned Harwood, for everything.

A Note on Sources

Unless otherwise indicated, archival sources for The Metropolitan Museum of Art are available via the Office of the Secretary Records, MMA Archives, with the exception of documents pertaining to the Museum of Primitive Art, which are held in the Museum’s Michael C. Rockefeller Department. Unless otherwise indicated, all references to the Nelson A. Rockefeller papers (abbreviated here to NAR) are to those held at the Rockefeller Archive Center (abbreviated to RAC) in Sleepy Hollow, New York. Accession numbers refer to works now in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, unless otherwise noted. The collection, with provenance as far as is known by the museum, is available online (www.metmuseum.org).

Notes

-

Joanne Pillsbury, “American Antiquities for an American Museum: Frederic Edwin Church, Luigi Petich, and the Founding Decades of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1870–1914),” in Collecting Mesoamerican Art Before 1940: A New World of Latin American Antiquities, ed. Andrew D. Turner and Megan E. O’Neil (Getty Research Institute, 2024), 235–58. ↩︎

-

Joanne Pillsbury, “Aztecs in the Empire City: ‘The People Without History’ in The Met,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Journal 56 (2021): 12–31. ↩︎

-

General Guide to the Museum Collections, Exclusive of Paintings and Drawings. Hand-book No. 10 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1881). ↩︎

-

General Guide to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Exhibition of 1888–89 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1888–89). ↩︎

-

“Opening of the New Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” The Art Amateur 48, no. 2 (1903): 47. ↩︎

-

John Taylor Johnson and Louis P. di Cesnola, “To the Members of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 13 (1882): 242. ↩︎

-

General Guide to the Museum Collections, Exclusive of Paintings and Drawings, 8. Often, however, ancient civilizations were elevated at the expense of present-day Indigenous inhabitants. Very few historic or contemporary Native American works entered the collection at this time. ↩︎

-

New York Mail and Express, September 10 and 17, 1898. ↩︎

-

See Pillsbury, “Aztecs,” for a longer discussion of this transfer. ↩︎

-

The first group of loans to Brooklyn, in 1935, was for one year; this was extended to “indefinite” the following year. A pair of Toltec architectural panels (93.27.1-2) was on loan to Brooklyn from 1939 to 1962. ↩︎

-

Pillsbury, “Aztecs.” ↩︎

-

MMA Archives, 02.18.313. Also see the unpublished reports of Elizabeth Easby from 1952 and 1956, mentioned below in note 18. ↩︎

-

Joseph Breck, Peruvian Textiles: Examples of the Pre-Incaic Period (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1930). ↩︎

-

John Goldsmith Phillips, “Peruvian Textiles: A Recent Purchase,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, 19, no. 4 (December 1960): 104. ↩︎

-

Joanne Pillsbury and Miriam Doutriaux, “Incidents of Travel: Robert Woods Bliss and the Creation of the Maya Collection at Dumbarton Oaks,” in Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks, ed. Joanne Pillsbury, Miriam Doutriaux, Reiko Ishihara-Brito, and Alexandre Tokovinine (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2012), 1–25. ↩︎

-

Francis Henry Taylor to the Members of the Board of Trustees, October 23, 1952, MMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Joanne Pillsbury, “The Pan-American: Nelson Rockefeller and the Arts of Ancient Latin America,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 72, no. 1 (2014): 18–27. ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Easby prepared two reports: The first, in 1952 (“Summary Report on M.M.A. Collection of pre-Columbian Art”), was followed by a more formal, illustrated report in 1956 (“Works of Art in the Pre-Columbian Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art”). Her reports built on an earlier report by “Miss Gash,” prepared in 1942, in response to a request from the Department of State in Washington for an inventory of Latin American holdings in US museums. ↩︎

-

On the Easbys as collectors, see Jennifer Jolly, Gabriella Jorio, Sarah McHugh, and Kenneth Roberton, As They Saw It: The Easby Collection of Pre-Columbian Art (Handwerker Gallery, Ithaca College, 2015). ↩︎

-

D. Easby to Antonio Orlandini, January 24, 1956, MMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Easby also organized the return of three objects from the AMNH in 1963; a larger number of the AMNH loans were recalled in 1980. Memo from Julie Jones to Douglas Newton, August 21, 1978, MMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Flora L. Phelps, “Masterpieces from Peru: The Nathan Cummings Collection at the Metropolitan Museum,” Américas 16, no. 12 (1964): 7–16. ↩︎

-

Memo from James Biddle to James Rorimer, March 19, 1963, MMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Memo from James Rorimer to Dudley Easby, January 9, 1956; René d’Harnoncourt to Nelson Rockefeller, December 8, 1967, Projects, Museum of Primitive Art, RG III 4L, Box 164, Folder 1665, NAR, RAC. See also a 1967 report on the AMNH loans prepared by Malcolm Delacorte, commissioned by Rorimer, complete with a ranking of the relative quality of the some 1500 works on loan there in the MMA Archives. ↩︎

-

John Canaday, “Governor Gives His Collection of Primitive Art to Metropolitan,” The New York Times, May 9, 1969. ↩︎

-

Nelson A. Rockefeller to Stephen Clark, December 16, 1942, Projects, Folder 1642, Box 161, NAR, RAC. ↩︎

-

Alfred H. Barr Jr., Letter to the editor, College Art Journal 10, no. 1 (1950): 57–59. ↩︎

-

“Rocky Road to Art,” Newsweek 68, no. 3 (July 18, 1966): 90. ↩︎

-

Draft, Museum of Indigenous Art Acquisitions policy, June 11, 1955, Projects, Series L (FA348), Folder 1679, Box 165, NAR, RAC. The museum changed its name to the Museum of Primitive Art in 1956. ↩︎

-

Nelson Rockefeller to William Kelly Simpson, November 7, 1956, Projects, MPA, Folder 1642, Box 161, NAR, RAC. See also “Rocky Road to Art.” ↩︎

-

Robert Goldwater, “Introduction,” Art of Oceania, Africa, and the Americas from the Museum of Primitive Art (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1969), n.p. ↩︎

-

Robert Goldwater to Nelson Rockefeller, April 26, 1957, Projects, Series L [FA348], Folder 1679, Box 165, NAR, RAC; Robert Goldwater to Gordon Ekholm, May 3, 1957, MPA Archive, MMA. ↩︎

-

Memo from Vera de Vries to Robert Goldwater, April 22, 1957, MPA Archive, MMA. ↩︎

-

MPA Archive, MMA; Interview with René d’Harnoncourt, WNYC, May 6, 1965. For a less positive assessment, see, for example, John Bernard Myers’s critical review of “René d’Harnoncourt: The Exhibitions of Primitive Art,” presented at the Museum of Primitive Art in 1970. “Exercises in Taste,” Craft Horizons 30, no. 3 (1970): 51–53. Attendance at MPA ancient American exhibitions averaged between three and five thousand visitors. ↩︎

-

The exhibition received three notices in The New York Times, September 17, 22, and 24, 1961. ↩︎

-

Art of Empire: 5,424 visitors; Jaguar’s Children: 5,576 visitors, MPA Archive, MMA. ↩︎

-

D’Harnoncourt to Rockefeller, March 21, 1962, personal papers, Art, Series C [FA340], NAR, RAC; Carol K. Uht Reference Files, Subseries 3, Folder 183, Box 24, MMA Archives. ↩︎

-

Oral History Project Interview with Julie Jones, April 21–22, 2015, transcript, p. 25, MMA Archives; Michael Gross, Rogues’ Gallery: The Secret Story of the Lust, Lies, Greed, and Betrayals That Made the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Broadway Books, 2009), 330; Nancy Lutkehaus, “The Bowerbird of Collectors: On Nelson A. Rockefeller and ‘Collecting the Stuff That Wasn’t in the Metropolitan,’” Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences 42 (2015): 133. Jones, Gross, and Lutkehaus cite d’Harnoncourt’s death as another factor in Rockefeller’s desire to close the MPA; plans to transfer the MPA to The Met, however, began over a year before d’Harnoncourt died. ↩︎

-

Projects, Museum of Primitive Art, Folder 1656, Box 163, NAR, RAC. ↩︎

-

Projects, Museum of Primitive Art, Folder 1654, Box 163, NAR, RAC. Title to the stela was transferred to Guatemala in 1970. ↩︎

-

Pillsbury, “The Pan-American.” ↩︎

-

A memo from Robert Goldwater to Thomas Hoving (May 26, 1970) outlines four reasons why the MPA could not stay on 54th Street, including lack of space, but the memo has the tenor of prepared talking points for the director prepared after the fact. ↩︎

-

Oral History Project Interview with Julie Jones, transcript, pp. 25–26. ↩︎

-

This meeting is referenced in a letter from d’Harnoncourt to Rockefeller, November 1, 1967, Projects, Series L [FA348], Folder 557, Box 60, NAR, RAC. I am grateful to Ellen Hoobler for calling my attention to Thomas Hoving’s memoir, which contains an alternative, and more self-serving view of the transfer, placing the “coup” of landing the Rockefeller collection later in time. Thomas Hoving, Making the Mummies Dance: Inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Simon & Schuster, 1993), 182–4, 193–5. ↩︎

-

Hoving exaggerated the success of the exhibition in comparison to MPA visitorship at times, stating that The Met’s show received more than the total number of visitors to the MPA in its lifetime. The MPA received 329,890 in the seventeen years it was open. Hoving records, Box 33, Folder 10, MMA Archive. ↩︎

-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art of Oceania, Africa, and the Americas from the Museum of Primitive Art: An Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1969); Robert Goldwater, “Art of Oceania, Africa, and the Americas,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 9 (1969): 397–410. ↩︎

-

Rockefeller to Arthur Houghton, president of The Met, August 15, 1969, Projects, Folder 1665, Box 164, NAR, RAC. ↩︎

-

Originally named the Department of Primitive Art, it became the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas in 1991; it is now known simply as the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing. ↩︎

-

On the agreement, see Milton Esterow, “Mexican Art Due at the Metropolitan,” The New York Times, January 31, 1968. ↩︎

-

William B. Macomber, “Report of the President,” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 112 (July 1, 1981–June 30, 1982): 4–7. See also, Grace Glueck, “A Spectacular New Wing,” The New York Times, January 24, 1982. ↩︎

-

Joanne Pillsbury, “Making the Ancient Modern: Nelson Rockefeller and René d’Harnoncourt,” in Collecting Mesoamerican Art, 1940–1965: Forging a Market in the United States and Mexico, ed. Megan E. O’Neil and Andrew D. Turner (Getty Research Institute Publications, in press). ↩︎