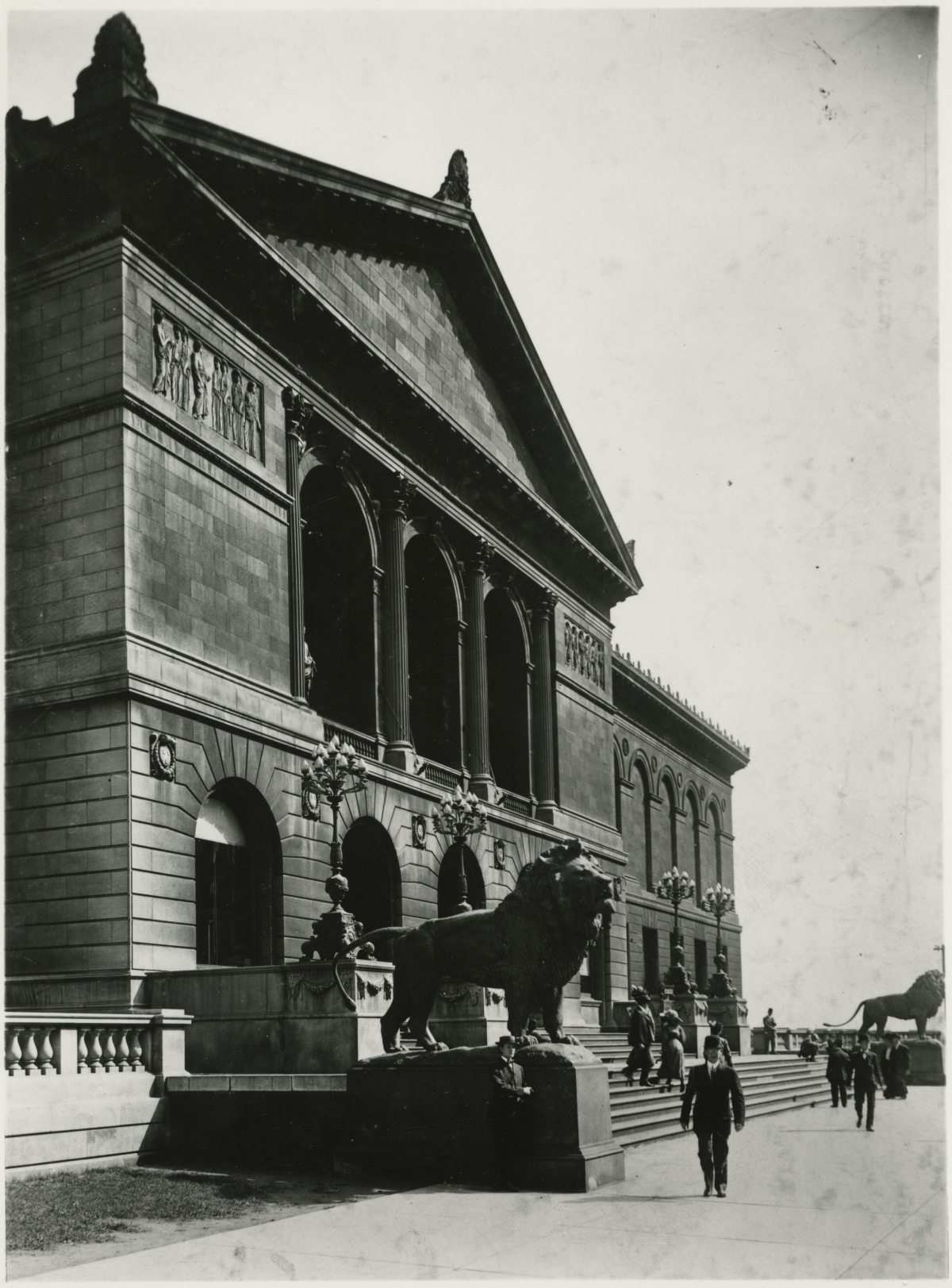

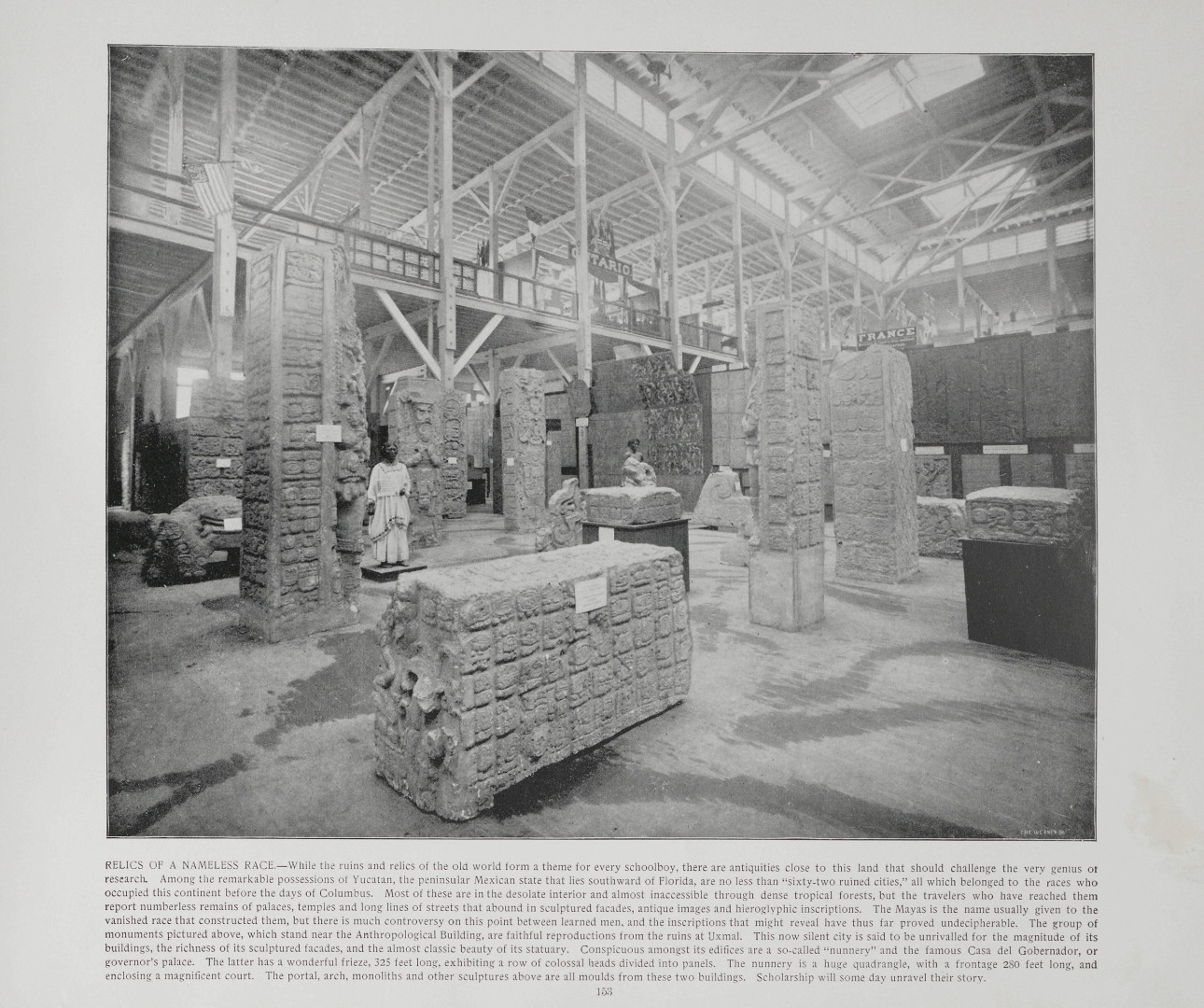

The Art Institute of Chicago’s building is a remnant of the city’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, which celebrated the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s voyage to the Americas. Columbus’s arrival in the “New World” was framed as a decisive moment within an overarching vision of a uniquely American cultural and industrial progress (fig. 1). The organizers sought to reveal the foundation of modern America through the scientific study of its “Native peoples.”1 The Exposition offered many their first engagement with ancient and Indigenous Americas through archaeology and ethnographic displays, as well as replicas of ancient sculpture and architecture recently discovered in Mexico and Central America (fig. 2).

The artifacts gathered for the Exposition became the founding collection for the new Columbian Museum of Chicago (later the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago Natural History Museum, and finally the Field Museum), while the Art Institute would move into the headquarters of the World’s Congress Auxiliary in the heart of Chicago. Manifesting the ideal “White City” presented by the Exposition, this Beaux-Art building has a facade etched with the names of Western history’s most important painters, sculptors, and architects—asserting itself as an art institution in the classical European model. The collections of the Art Institute long reflected this perspective, with no interest in works from the ancient or Indigenous Americas. Exhibiting pre-Columbian and North American objects in natural history or anthropological institutions, rather than an art museum, was the standard practice of the day; it would take several decades until these “artifacts” were regarded as “art” and displayed alongside other celebrated artistic traditions.

Modest Gifts and Industrial Inspiration

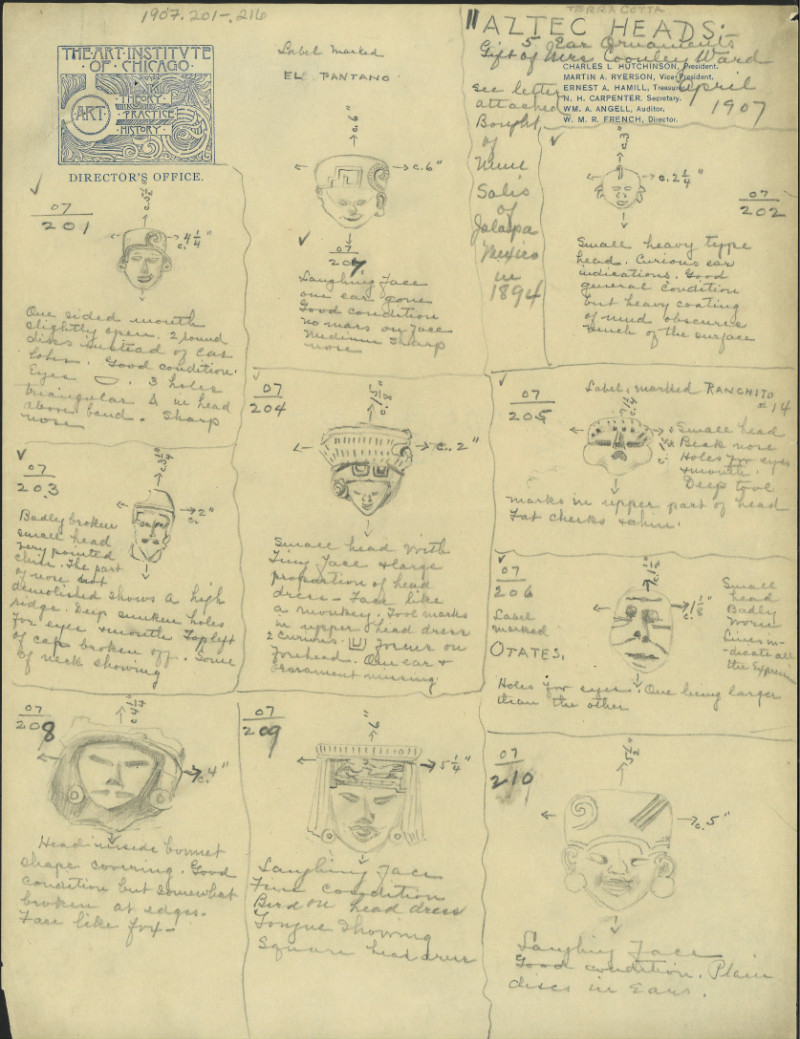

Few ancient or Indigenous American objects entered the Art Institute’s permanent collection during the fifty years after its founding in 1879. They typically were modest gifts from civic-minded local philanthropists, such as the assortment of broken clay figures, earflares, and spindle whorls from ancient Mexico given in 1907—the first works from Mesoamerica acquired by the museum (fig. 3). With no curatorial department dedicated to the collection and display of these works, most were placed within the Decorative Arts department, “all but forgotten in various storerooms.”2

One of the Art Institute’s earliest displays of ancient American objects was the addition of Andean textile fragments to a “History of Textiles” installation in 1930. Bessie Bennett—then curator of Decorative Arts—explained that including textiles from “our own hemisphere” would be “of great service not only to art students but to manufacturers who seek inspiration for new patterns and color schemes.”3

Katharine Kuh and the Aesthetics of “Primitive Art”

Although the introduction of modern art to Chicago was fraught, it was through early-twentieth-century modernism—specifically the interest in the aesthetics of “primitive art”—that ancient and Indigenous American works of art gained their place at the Art Institute.4 Katharine Kuh (1904–1994) was essential to bringing modern avant-garde artists and non-Western art to the attention of the city and the museum (fig. 4). Kuh’s desire to be a pioneer led her to a career as a gallerist, art educator, curator, art consultant, and critic, specializing in modern art.5 She learned about a new approach to teaching and displaying art through Alfred H. Barr Jr., with whom Kuh took an art history class during college. Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA; 1929–40), would become Kuh’s mentor and collaborator.6 His advocacy of art of the day, visually focused methods for teaching art, explorations of the aesthetic connections between modern and non-Western art, and formalist approach to art installation were fundamental to Kuh’s own practice.7

In 1935, Kuh opened the first commercial gallery in Chicago devoted to avant-garde artists (fig. 5). Contemporary works were often juxtaposed with “various kinds of primitive art,” reflecting a modernist perspective in which non-Western art was embraced as a source of visual inspiration and authenticity.8 Kuh’s gallery opened just two years after MoMA’s influential exhibition American Sources of Modern Art, which presented pre-Columbian objects as works of art in an art museum through a formalist, aesthetic appreciation.9

Kuh found it difficult to find buyers for the avant-garde in conservative Chicago, and with World War II limiting her access to the European artists she promoted, she was forced to close her gallery in 1942. Kuh’s creative engagement with modern art was widely recognized, and she was hired by the director of the Art Institute, Daniel Catton Rich (1904–1976). Initially working in public relations, she was soon appointed to lead the Gallery of Art Interpretation, which Kuh transformed into an experimental museum space whose primary objective was to teach adult audiences about contemporary art.10

Following Kuh’s intention “to teach art visually,” labels and texts were eliminated as much as possible, encouraging direct, uninterrupted, visual engagement with individual works of art.11 The Gallery of Art Interpretation also “focus[ed] on the art of the present and recent past and [related] it not just to the history of western art but to that of other cultures (oriental, pre-Columbian, African, folk, etc.).”12 Audiences were introduced to visual vocabularies different than traditionally used in Western art, inviting consideration of color, texture, and space.

Kuh’s first installation in the Gallery of Art Interpretation was an “explanatory exhibition” that complemented the Art Institute’s 1944 exhibition on José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913), the first large-scale presentation of the artist’s work in the United States (fig. 6).13 Described as a “condensed introductory show to familiarize patrons with the background and technique of the artist represented in the main exhibition halls,” Kuh’s exhibition provided a foundation for the general public to approach the work of Posada, a largely unknown artist.

Kuh’s exhibition posed the question: “Who is Posada?” To answer, Kuh created a free-flowing space—designed with Bauhaus architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe—organized around a series of explanatory ideas. The installation visually engaged with the audience using “blow-ups, photographs, actual objects, diagrams, and, of course, original prints” and included a variety of objects from Mexico’s past and present.14 Highlighting Posada’s engagement with Mexican culture, the exhibition included works of art from the country’s popular and ancient traditions; however, because the Art Institute did not have a collection of significant pre-Columbian works, several objects had to be borrowed from Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, including an Aztec Coiled Rattlesnake (48126).15

The Eduard Gaffron Collection

With her experience working with non-Western objects, Kuh understood the significance when she learned of an opportunity for the museum to acquire one of the largest collections of ancient Andean art in private hands: the Eduard Gaffron Collection. In late 1948, Kuh met Dr. Hans Gaffron, then an associate professor at the University of Chicago, who told her about his father’s collection, which he and his sister, Mercedes Gaffron, had inherited upon his death in 1931. Informed of the family’s desire to determine the future of the collection, Kuh encouraged Hans to write to Rich, the Art Institute’s director. This was the catalyst that led to the museum’s purchase of the famed Gaffron Collection and, ultimately, the establishment of a new department dedicated to primitive art.16

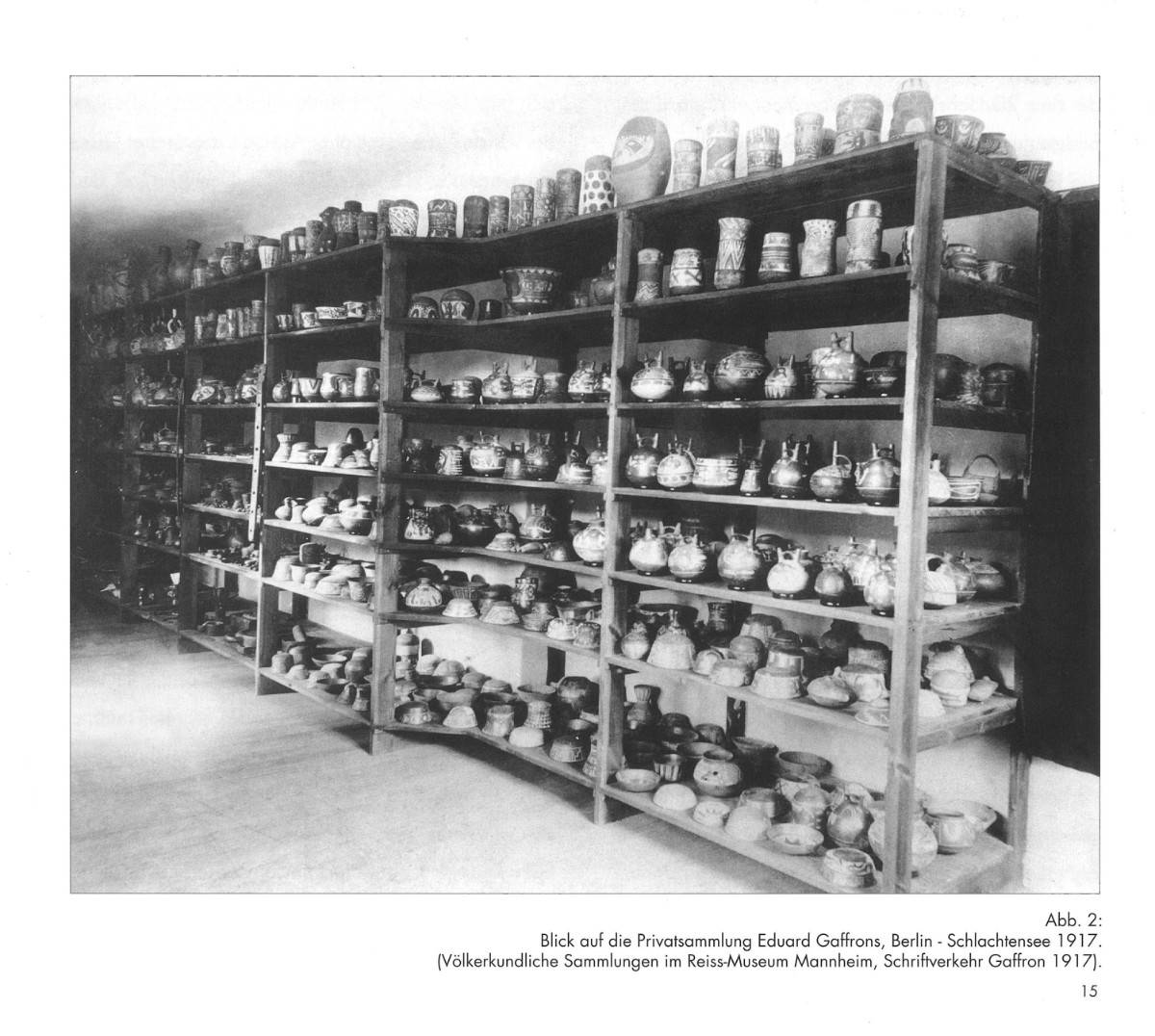

Eduard Gaffron was a German doctor who lived in Peru from 1892 to 1912, during which time he actively collected ancient Peruvian works (fig. 7). Most of his collection likely was purchased through an informal market of looted objects; some may have been acquired during unofficial excavations or by exchange in lieu of payment for his medical services.17 While ancient Peruvian art and culture was generally overlooked at the time, Gaffron’s interest would have suited his status in Peru where, by the mid-nineteenth century, “the display of antiquities in parlors and salons was confined to the highest strata of Lima society . . . to own and to display antiquities, to bring them out and show them to one’s guests after dinner, appears to have constituted an element of elite sociability in the city of Lima.”18

Gaffron returned to Berlin in 1912 with his collection, which he continued to refine through sales, purchases, and exchanges, ultimately numbering in the tens of thousands.19 The Eduard Gaffron Collection was widely known among scholars and fellow enthusiasts and was published several times in German, English, and French, initially in 1924 by Walter Lehmann and Heinrich Ubbelohde-Doering.20 Gaffron donated and sold large portions of his holdings to museums and private collectors in Europe and the United States so that at the time of his death, the collection numbered approximately 1,300 objects, mostly ancient Andean ceramics but also textiles, metalwork, and stone. Because of the upheavals in Germany and restrictions placed on the export of art, when Hans left the country in 1931, the bulk of the collection remained in Germany, stored at Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde, Munich, where it had been under the care of Ubbelohde-Doering since 1912 (fig. 8).

Following Kuh’s suggestion, Hans wrote to Rich, asking for advice and help in getting his father’s collection out of Germany.21 Rich was receptive to the message, not only as a supporter of modern art but also a collector of primitive art.22 With help from Ubbelohde-Doering, the Gaffron Collection was shipped to Chicago and placed on long-term loan with the museum. Because none of the Art Institute’s existing curatorial departments oversaw pre-Columbian works, the loan was arranged through the department of Decorative Arts, led by curator Meyric R. Rogers, and Alan R. Sawyer, then the assistant to the curator.

The Art Institute introduced the Eduard Gaffron Collection to the public in a series of special exhibitions beginning in April 1952 (fig. 9). The news release referred to the works as “treasures,” emphasizing their aesthetic qualities and artistic excellence.23 A typescript description of the exhibition asserts the Art Institute’s role as an art museum in its presentation of this previously overlooked area: “The current exhibition is designed to bring out the artistic significance of the material rather than its historical or archaeological meaning.”24

These objects were regarded as art and installed as such: Photographs of the exhibition show simplified casework and minimal didactics, allowing for the audience to visually engage with individual works. Furthermore, the vessels were generously spaced, with many elevated on small lifts, signaling their special status. It is also of note that these pre-Columbian works were not placed in juxtaposition to modern paintings or sculptures but were instead presented on their own.

In 1953, Hans and Mercedes Gaffron explained their decision to sell to the Art Institute in a letter to Rogers.25 Both wanted to keep the collection together, hoping that by doing so it would continue to have a connection to their father. In a letter to her brother that Hans shared with Rogers, Mercedes also responded positively to the Art Institute’s art-focused installation, stating: “It would please me particularly if the collection remained in Chicago with Dr. Rogers who exhibited it so prettily instead of collecting dust in a museum of natural history.”26

Purchasing the Eduard Gaffron Collection was a major undertaking for the museum. If successful, the museum would need to create a new collecting area dedicated to the acquisition and display of primitive art. Rogers and Rich were aware of the increasing interest in non-Western art in the US and abroad by museums and private collectors, that prices for these works of art were rising, and opportunities to enter the field were limited.27 They advised that the purchase be finalized quickly.28

Nathan Cummings and Chicago Collectors

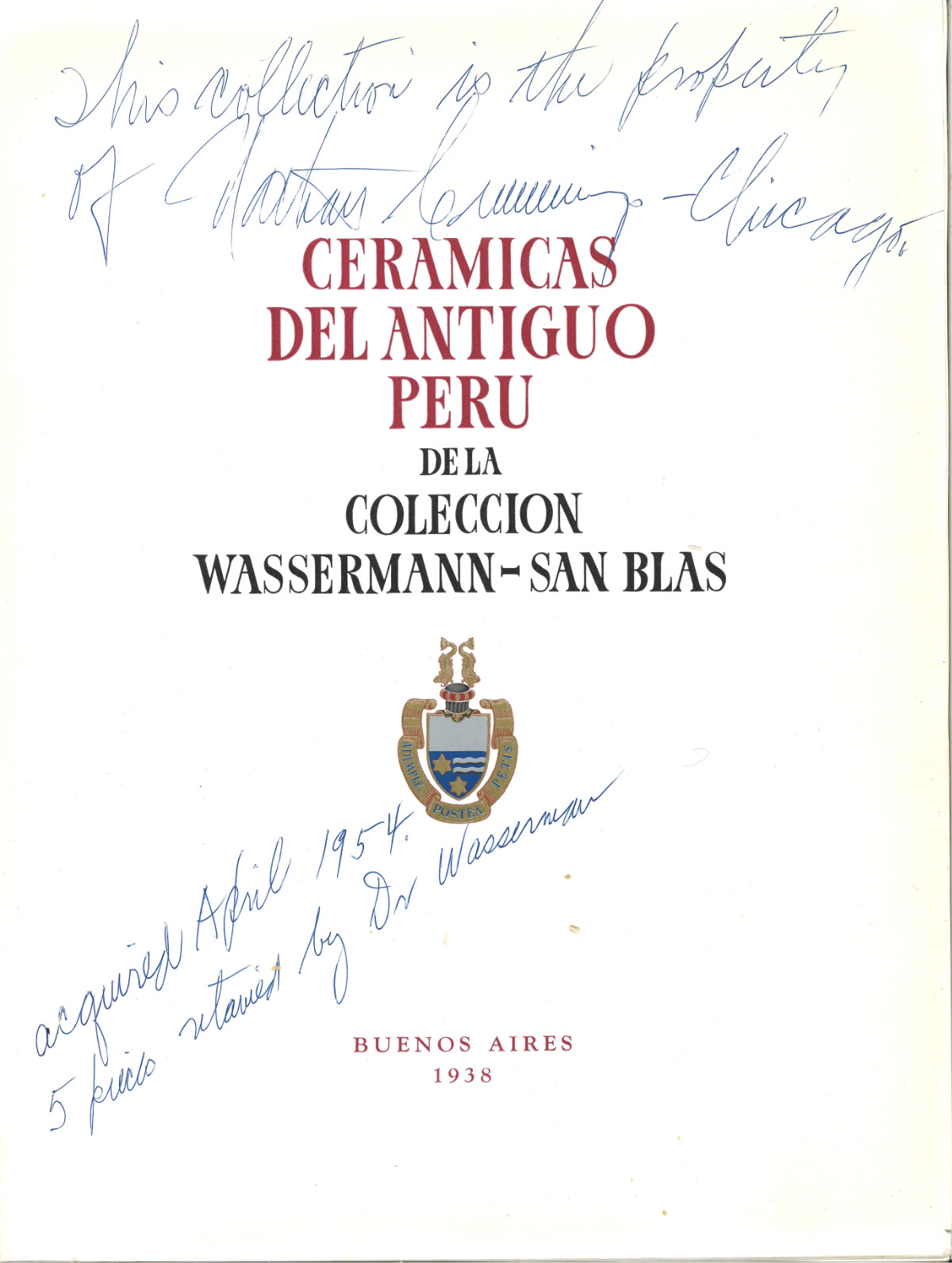

One influential group encouraging the Art Institute to establish a new department for primitive art was Chicago collectors, particularly those with an interest in modern art and collections that included non-Western works. While the Art Institute was pursuing the Gaffron Collection, Nathan Cummings, a Chicago businessman who had an important collection of paintings and sculptures from the mid-nineteenth century to contemporary works, purchased another major private collection of ancient Andean art, the Wasserman-San Blas Collection (fig. 10). As B. J. Wassermann-San Blas explained in the preface to his 1938 catalog, his collection—totaling approximately 1,500 objects—was begun by his maternal grandmother during a visit to Peru a century before, to which he added through unauthorized excavations and purchases on the open market.29 In 1954, Wassermann-San Blas offered the works for sale to several private collectors, including Cummings. Cummings had known the seller for years and—after some consideration and a drop in price—he purchased the collection that spring.30

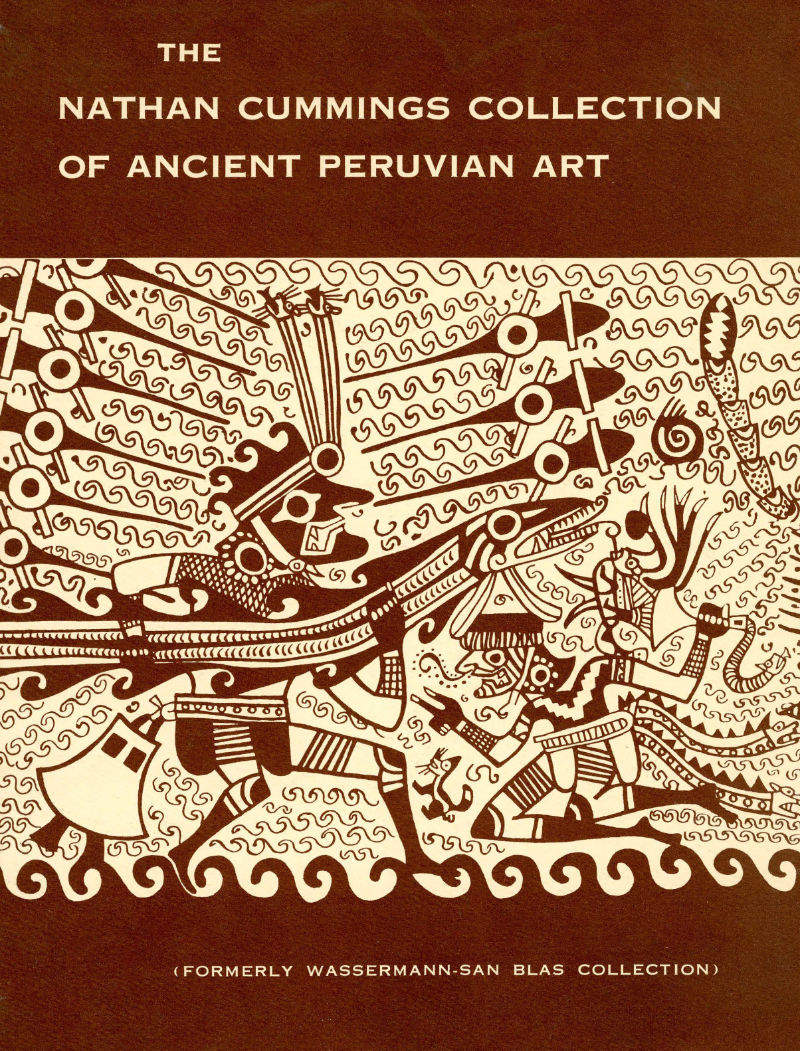

Later that year, Cummings lent nearly two hundred ancient Andean ceramics to the Art Institute for a special exhibition that would later travel to museums in the US, Canada, France, and Italy. Cummings worked with Sawyer—then the Assistant Curator of Decorative Arts—to produce “a handbook” of his newly acquired collection, rebranding it as The Nathan Cummings Collection of Ancient Peruvian Art (fig. 11). In the introduction to the small catalog, Cummings stated that his interest in ancient Andean works was as a collector of modern art: “Although most of the pottery was made more than a thousand years ago, by Indians whose tribal names are strange to our ears, it is so pleasing to the modern eye that it stands as a challenge to the work of today’s artists.”31

A New Department for Primitive Art

The purchase of the Gaffron Collection in April 1955, along with a promised gift from the Nathan Cummings Collection, were envisioned as a “cornerstone on which to build a new division of Primitive Arts.”32 In the 1954–1955 Annual Report, Rich explained the rationale for the founding of a new department dedicated to a collecting area previously ignored by the museum: “One of the great discoveries of the twentieth century is the fascinating series of interlocking cultures broadly called Pre-Columbian. Regarded as mere curios by their discoverers, and later crowded into the cases of ethnographic museums, these ancient sculptures, ceramics, and textiles are now being studied seriously, and are recognized as works of art worthy to rank with many of the greatest expressions of the Orient and Europe.”33

At this time, questions were being raised—mostly by anthropologists—asking if art museums should be collecting these works at all. In a 1958 essay, Harry L. Shapiro, chair of the Department of Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History, rejected efforts by US art museums to acquire non-Western works, arguing, in part, that the aesthetic approach of art museums removed context: “Primitive art belongs with its culture and should be exhibited in reference to it. Such a task belongs in the anthropological field.”34

The Art Institute responded to this opposition by differentiating itself from the Chicago Natural History Museum. At the first meeting of the Committee on Primitive Art held on April 29, 1957, Rogers addressed concerns over “future relations” with the Chicago Natural History Museum and other scientific institutions, asserting: “There will be no conflict in the field of Primitive Art since scientific museums are interested in collecting ethnographic materials, whereas the Art Institute will stress only the esthetic side and exhibit primitive objects for their artistic value.”35

Sawyer—who was selected as the first curator of the new Primitive Art department in 1958 despite having little training in non-Western art—asserted that the two “sister institutions” had qualitatively different approaches to the same material. In an essay promoting one of the first exhibitions presented by the Primitive Art department—an exhibition of Oceanic art—Sawyer hailed the Chicago Natural History Museum’s Oceanic collection as one of the finest and most extensive in the world; yet, through “careful selection and presentation [the Art Institute] sought to emphasize the great artistic achievements of the Oceanic peoples, so that they can be appreciated in relation to the great creative expressions of European and Asiatic peoples on view in our other galleries.”36

Growing a Collection of Primitive Art

One difficulty faced by the new department was the collections’ lack of depth and breadth, with approximately 1,500 ancient Andean ceramics and textiles supplemented by fewer than one hundred works from other culture areas. At the first meeting of the committee, members recognized that the ancient Andean works numbered far in excess of what could be displayed and decided that “only the finest objects were to be retained, the balance traded or sold to dealers, collectors, and museums in order to acquire additional objects of top quality.”37 Over the course of subsequent meetings, Sawyer and the committee reviewed the Gaffron Collection holdings, identifying works for possible disposal.

Sawyer would leave the museum in 1959, so the final dispersal of “surplus” Andean works would fall to Allen Wardwell, who was appointed as the Assistant Curator of the Primitive Art department in 1960. Although trained in decorative arts, Wardwell’s master’s thesis focused on Polynesian art, and he previously had worked on an African sculpture exhibition at the Museum of Primitive Art. In 1961, the committee authorized the exchange of ancient Andean ceramics, gold, and featherwork with the Denver Art Museum, Milwaukee Public Museums, Field Natural History Museum, and the New York dealer Henri Kamer for works of art from Oceania, Africa, and North American works in their collections.38

As the department continued to seek opportunities to expand its holdings, it continued to rely on loans from local private collectors and the Chicago Natural History Museum. This arrangement was made explicit with the first major exhibition organized by the department, Primitive Art from Chicago Collections, which opened at the end of 1960 (fig. 12). In the exhibition catalog, Wardwell remarked that more than 250 objects had been loaned from fifty-three sources, demonstrating “the widespread interest in the so-called ‘primitive arts’ in Chicago,” yet most lenders had only a few pieces in their collections.39 He also acknowledged “the most important collection of primitive art in Chicago is the vast amount of material collected from an anthropological standpoint by the Chicago Natural History Museum.”40

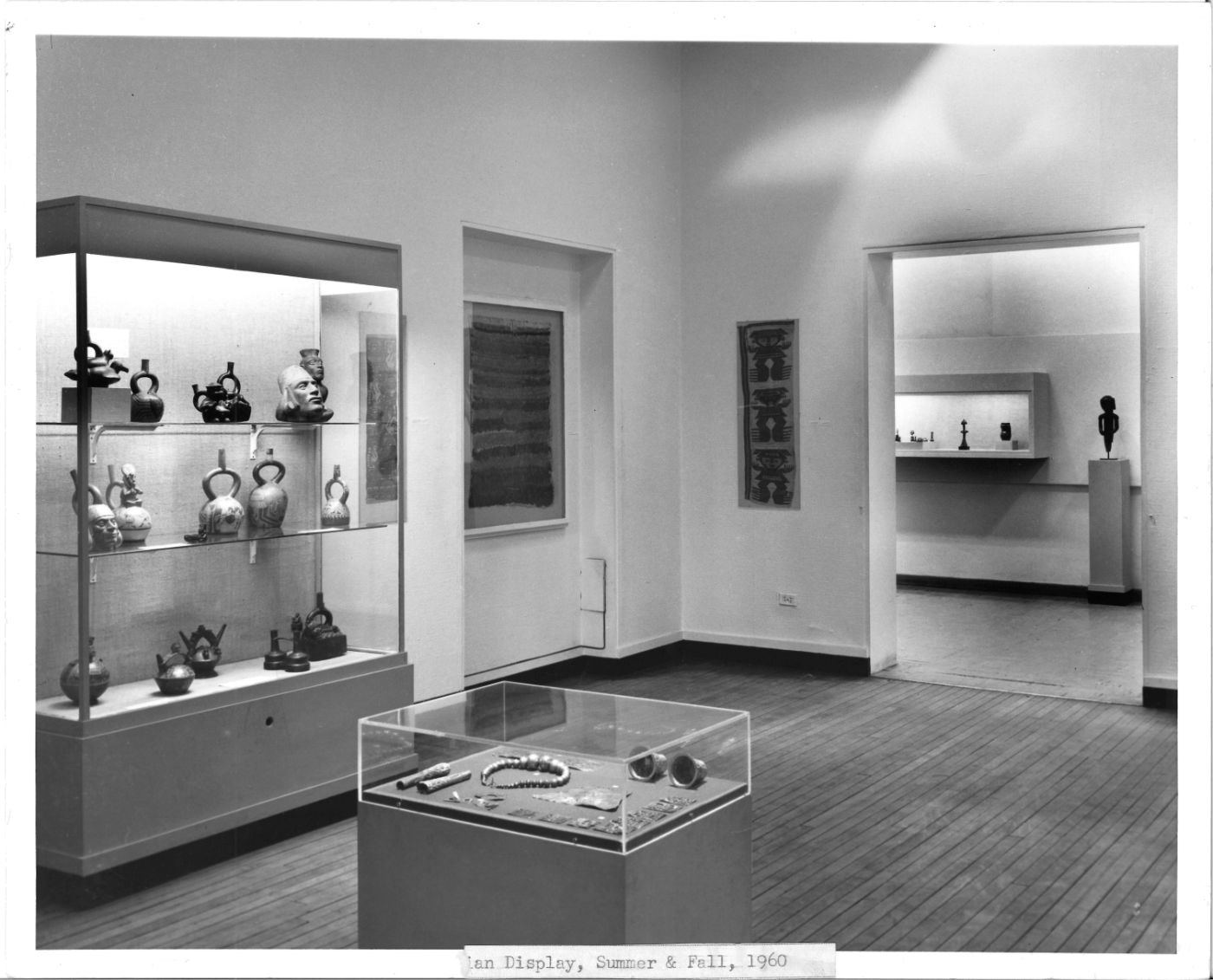

Emphasizing the aesthetics of the works, the installation of Chicago Collections was stark, with wide open spaces. This allowed works from different cultures, regions, and time periods to be seen in a single glance, which reinforced the assumption of a cohesive category of primitive art. Discreetly placed area maps and minimal didactic texts offered little distraction to visual engagement with the objects, but they provided only minimal guidance for the audience.

The focus on individual works of art and their formal qualities was also the design approach in the early permanent collection galleries. A photograph from the 1960s shows a decontextualized, modernist display, featuring simple casework, a small selection of works, and minimal text (fig. 13). A later description of the early primitive art installation suggests that, due to the limitations of the space allocated to the collection, artwork was displayed according to size rather than style or place of origin, prioritizing visual and formal inquiry over contextual.41

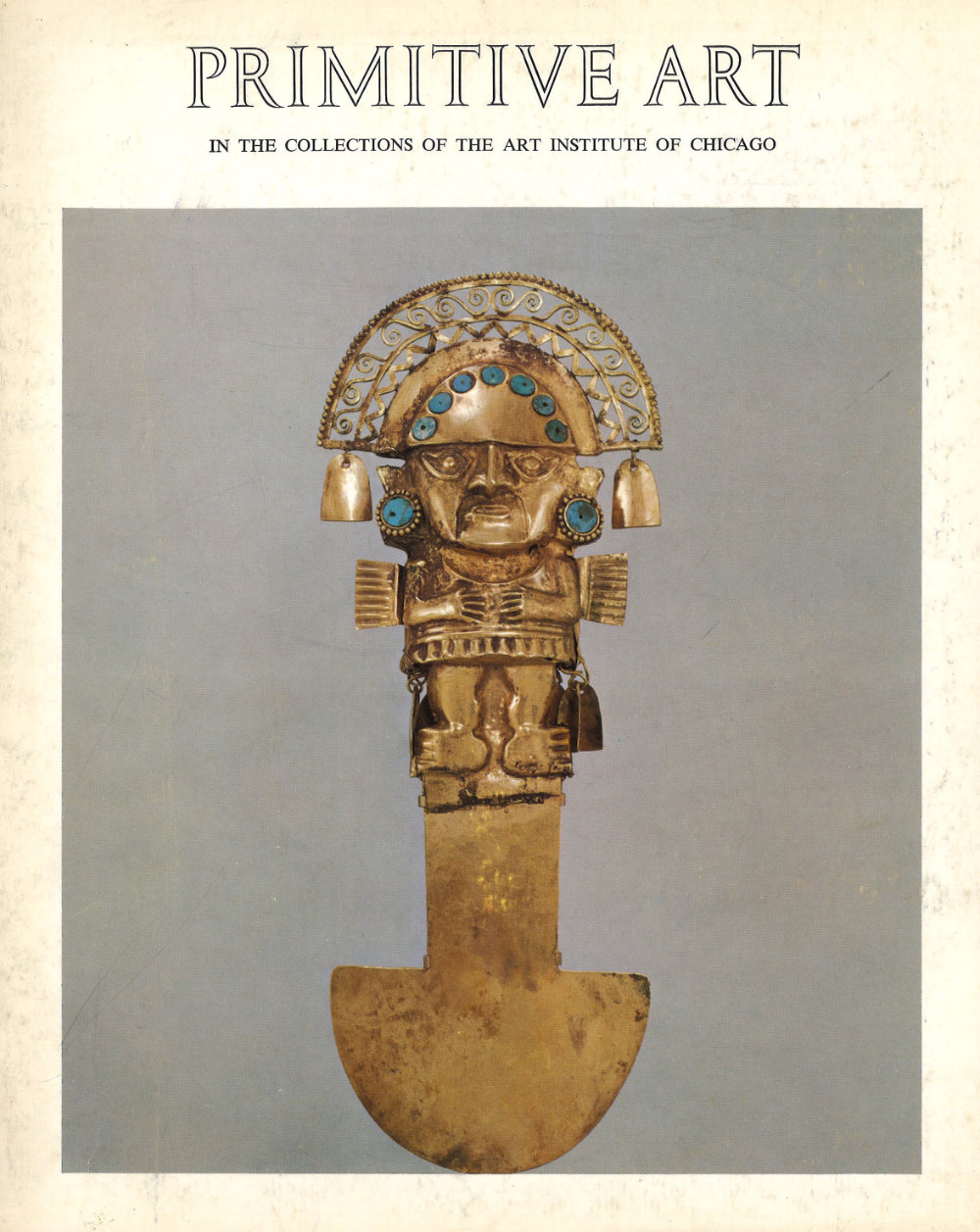

Even with limited funds, the young department made purchases to better present the breadth of its collecting areas, selecting singular masterpieces that would act as keystones for the collection. In the 1960s, works from across the ancient Americas were acquired, including the Teotihuacan Mural Fragment (1962.702), Coclé Pedestal Bowl (1963.389), Chimú Tumi (1963.841), and Maya Ballplayer Panel (1965.407). In 1965, the department published its first collection catalog, Primitive Art in the Collections of The Art Institute of Chicago, a small book featuring eighty works from across non-Western cultures (fig. 14). In his introduction, Wardwell acknowledged that “these collections will never attain the wealth and depth of those in older and better endowed institutions,” however, he hoped that, in some small way, “representation of the great artistic achievements of these exotic cultures can be imparted to those who visit the Art Institute of Chicago.”42

The succeeding curator of the department, Evan Maurer, fundamentally transformed how the collection was presented, reflecting increased specialization in academia and research in the field.43 Although Maurer was trained as a modernist with little experience with primitive art, his 1978 reinstallation of the permanent collection galleries moved away from generalized and formalist displays. Instead, he offered a deeper understanding of the works of art by situating them within their specific cultural contexts. The collection also was relocated to larger galleries, allowing for separate installations of the three primary culture areas: Americas, Oceania, and Africa. Each was further organized according to region, style, and medium. Juxtapositions of artworks were used to highlight similar motifs across media within a single culture and to demonstrate differences in regional art styles. To further emphasize the vast diversity of the department’s holdings within the distinct collecting areas, Mauer changed the name of the department to Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

Following the departure of Maurer in 1981, the museum hired Richard F. Townsend, the first curator of the department trained in anthropology and art history whose expertise was in the arts of the Americas, having conducted fieldwork and studies in the US Southwest, Mexico, and Peru. However, two principles of Townsend’s work resonated with earlier approaches to ancient and Indigenous American objects at the museum: the prioritization of aesthetic excellence and visual engagement with individual works of art and the concept of a unifying sacred world view shared by the diverse cultures of the Americas.

With a career at the Art Institute lasting thirty-five years, Townsend had a profound impact on the museum, including organizing two major permanent collection reinstallations and six special exhibitions. At the outset, Townsend refined the collection by deaccessioning lesser quality and redundant material, including Oceanic works, an area that had never been actively acquired.44 He then reinstalled the collection within three adjacent, yet separate, galleries that underscored the newly defined collecting areas: arts of Africa, the ancient Americas, and Indigenous North American Indian (fig. 15). Recognizing the advancements of academic fields of study and the need for specialized training, a separate curatorial position was established to oversee African arts in 1987.45

The 1992 special exhibition The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes reflected Townsend’s approach to the arts and cultures of the Americas (fig. 16). This exhibition explored the essential integration of human society with the sacred natural world. As Townsend explained: “The gallery presentation was designed to show that art, architecture, and ritual were engaged in religious dialogue with the deified forms of earth, sky, and water. We intended to show that the visual arts played an active role in the ritual cycle of natural and social renewal.”46

Held during the quincentenary of Columbus’s arrival in North America, the exhibition did not address European impact on the Americas; instead, it showcased the great diversity and artistic accomplishment of the pre-Columbian past. The installation presented 280 objects from twenty-four cultures, contextualized by large-scale photographs of natural environments and man-made structures—the “sacred landscapes” of the exhibition theme. Although some argued that the conceptual underpinning was lacking from the exhibition, others observed that the installation invited aesthetic appreciation of the works: As one reviewer noted, “Those who put quality first can also rejoice, for there is little in this exhibition . . . that does not rivet the eye.”47

I joined the department in 2005, working alongside Townsend until his retirement in 2016. One major project during this time was the 2011 reinstallation of the permanent collection into much larger galleries (fig. 17).48 Renamed “Indian Arts of the Americas,” the collection included traditional works of art founded in ancient and Indigenous customs and practices united by a shared world view. The galleries presented a wide range of works in a large open space, loosely divided into three sections, one for each of three major culture areas. A centrally placed text explained the connection between communities and the sacred world—a theme reinforced by a video displaying landscapes, ritual, and architecture—while a map of the hemisphere noted the location of the diverse cultures: North American, Mesoamerican, and Andean.49 Although organized by geographic region and culture, open passages between each section allowed visitors to see the broad scope of the collection, encouraging audiences to make visual connections across culture, time, and space.

Casework was designed to be unobtrusive, and didactics were kept to a minimum and separated from the objects, removing distraction and distance between the visitor and the artwork. Townsend stated: “Our emphasis here is rather to bring out the masterpieces . . . and to display these in a way that they can speak for themselves in terms of their formal qualities—form, color, and shape.”50

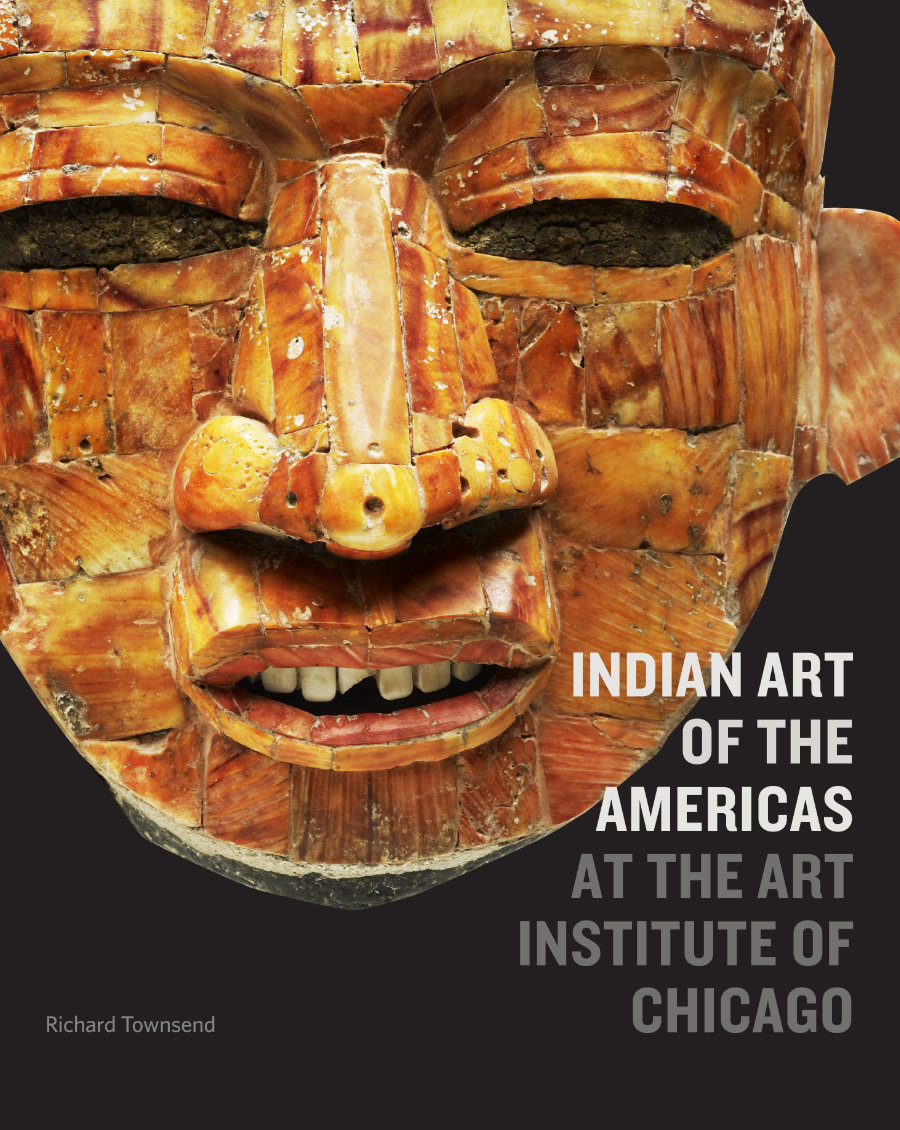

The culmination of Townsend’s work at the museum was the publication of a collection catalog, the first since Wardwell’s in 1965 (fig. 18).51 Although the book presents over 350 individual works of art, each discussed within their specific cultural context, Townsend’s vision of a unified American sacred worldview connects them all.

A New Perspective: Arts of the Americas

In 2020, one of the last traces of the departments’ “primitive art” origins was ended, as the arts of Africa and the arts of ancient and Indigenous Americas were separated and placed in different curatorial departments. The American objects joined with what previously was known as American Art—works made in the US from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries—in a newly conceived Arts of the Americas department. Currently, under the curatorship of Andrew Hamilton, the museum has also broadened its collecting of Indigenous American art to include contemporary artists and their works. This reorganization and expanded definition of American art has resulted in the integration of Indigenous arts into the American art galleries, offering dialogue among diverse works in the collection from across the hemisphere and enabling new and more complex narratives (fig. 19).52

The changing assessment of ancient and Indigenous works at the Art Institute of Chicago demonstrates how external perceptions determine their place in the museum. Initially, objects were disregarded as “artifacts” better suited for natural history or anthropological institutions; later, they were incorporated into the collection as decontextualized “primitive” works within a modernist framework. Today, through a deeper understanding of the artists and communities in which objects were made and used, ancient and Indigenous works are valued as unique and compelling artistic expressions. Objects do not change, but through reconsideration, the Art Institute offers a space for more meaningful engagement with the distinctive visual traditions of the ancient and Indigenous Americas.

I would like to thank Victoria Lyall and Ellen Hoobler, the staff of the Denver Art Museum and the Mayer Center for Ancient and Latin American Art for organizing such an important symposium, and the other contributors for generously sharing their knowledge. I also want to recognize my exceptional colleagues from the Art Institute of Chicago’s Archives and Research Center: J de la Torre, Dave Hofer, Alexandra Katich, Nathaniel Parks, and Bart Ryckbosch; and Kylie Escudero, who expertly assisted with acquiring images and rights.

Notes

-

Trumbull White and William Igleheart, The World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893: A Complete History of the Enterprise (P. W. Ziegler & Co., [1893]); Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, Mexico at the World’s Fair: Crafting a Modern Nation (University of California Press, 1996). ↩︎

-

Allen Wardwell, Primitive Art in the Collections of the Art institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1965), [i]. ↩︎

-

Bessie Bennett, “Some Ancient American Textiles,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 24, no. 7 (1930): 90; see also, Ann Marguerite Tartsinis, An American Style: Global Sources for New York Textile and Fashion Design, 1915–1928 (Bard Graduate Center, 2013). ↩︎

-

Judith A. Barter and Brandon K. Ruud, “‘Freedom of the Brush’: American Modernism at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Judith A. Barter et al., American Modernism at the Art Institute of Chicago: From World War I to 1955, (Art Institute of Chicago, Yale University Press, 2009), 11–40; Andrew Martinez, “A Mixed Reception for Modernism: The 1913 Armory Show at the Art Institute of Chicago,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 19, no. 1 (1993): 30–57+. ↩︎

-

Avis Berman, “An Interview with Katharine Kuh,” Archives of American Art Journal 27, no. 3 (1987): 6. See also Susan F. Rossen and Charlotte Moser, “A Primer for Seeing: The Gallery of Art Interpretation and Katharine Kuh’s Crusade for Modernism in Chicago,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 16, no. 1 (1990): 6–25+. ↩︎

-

Irving Sandler and Amy Newman, ed., Defining Modern Art: Selected Writings of Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (Harry N. Abrams, 1986); Mary Anne Staniszewski, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art (MIT Press, 1998). ↩︎

-

Rossen and Moser, “A Primer for Seeing,” 8. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Holger Cahill, American Sources of Modern Art (Museum of Modern Art, 1933). ↩︎

-

In 1954, Kuh became the Art Institute’s first curator of modern painting and sculpture. ↩︎

-

Katharine Kuh, “Explaining Art Visually,” Museum 1, nos. 3–4 (1948): 148–55+. ↩︎

-

Rossen and Moser, “A Primer for Seeing,” 8. ↩︎

-

Katharine Kuh, “Posada of Mexico,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 38, no. 3 (1944): 42-44; Fernando Gamboa, Carl O. Schniewind, and Hugh L. Edwards, Posada: Printmaker to the Mexican People (Art Institute of Chicago, 1944). ↩︎

-

Kuh, “Posada of Mexico,” 44. ↩︎

-

The Field Museum acquired the Aztec Coiled Rattlesnake (catalog no. 48126) in 1897 as a gift from Allison V. Armour. ↩︎

-

For a discussion of the history of the department from the perspective of African Art, see Kathleen Bickford Berzock, “Changing Place, Changing Face: A History of African Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Representing Africa in American Art Museums: A Century of Collecting and Display, ed. Kathleen Bickford Berzock and Christa Clarke (University of Washington Press, 2011), 150–67. ↩︎

-

Claudia Schmitz, “Eduard Gaffron und das Schicksal seiner archäologischen Sammlungen aus Peru,” Mitteilungen der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 22 (2001): 73–78; Claudia Schmitz and Claus Deimel, Geschenke der Ahnen: Peruanische Kostbarkeiten aus der Sammlung Eduard Gaffron: Konstruktion und Wirklichkeit einer Kultur (Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig, 2001). ↩︎

-

Stefanie Gänger, Relics of the Past: The Collecting and Study of Pre-Columbian Antiquities in Peru and Chile, 1837–1911 (Oxford University Press, 2014), 115. ↩︎

-

An article announcing the acquisition stated the Gaffron Collection originally numbered about forty thousand objects. See “Gaffron Collection Acquired,” The Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 50, no. 1 (1956): 3. However, Schmitz and Deimel suggest it was approximately eleven thousand works (Geschenke der Ahnen, 8). ↩︎

-

Kunstgeschichte des Alten Peru (E. Wasmuth, a.g. 1924). ↩︎

-

H. Gaffron to D. C. Rich, June 3, 1948, Institutional Archives, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

Joanne Behrens, “A Short History of the Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas,” unpublished report, October 1985, Arts of the Americas research files, Art Institute of Chicago; Transcript interview with Katharine Kuh. ↩︎

-

“Treasures of Ancient Peruvian Art,” The Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 46, no. 2 (1952): 28–29; News release, “Arts of Peru—The Edward Gaffron Collection on view at the Art Institute,” April 28, 1952, Institutional Archives, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

Art Institute of Chicago, Typewritten description “Art of Ancient Peru: The Eduard Gaffron Collection,” 1952, Institutional Archives, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

H. Gaffron to M. Rogers, January 11, 1953, Arts of the Americas research file, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

Mercedes Gaffron, translated by H. Gaffron and shared with M. Rogers, December 10, 1952, Arts of the Americas research file, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

Daniel Catton Rich, Minutes for Report, Committee on Buckingham Fund, December 8, 1954, Institutional Archive, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

This sense of urgency likely was, in part, due to the failed negotiations with Walter and Louise Arensberg for their collection of contemporary and pre-Columbian art. Rich and Kuh worked closely with the Arensbergs for years; Kuh developed the 1949 exhibition of their modern art collection, shown exclusively at the Art Institute. Rich and Kuh were hesitant to include pre-Columbian works in the exhibition, which Kuh did not feel experienced enough to evaluate. Ultimately, the Arensberg’s donated their collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. See Berman, “An Interview with Katharine Kuh,” 28; Mark Nelson, William H. Sherman, and Ellen Hoobler, Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L. A. (Getty Research Institute, Getty Publications, 2020); and Ellen Hoobler, in this volume. ↩︎

-

Bruno John Wassermann San-Blas and Heinz Lehmann, Céramicas del Antiguo Perú de la colección Wassermann-San Blas (S. A. Casa Jacob Peuser, 1938), preface. Translated by the author. ↩︎

-

Memo from Alan R. Sawyer to Daniel C. Rich, March 18, 1954, Arts of the Americas department records, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

Alan R. Sawyer, The Nathan Cummings Collection of Ancient Peruvian Art (Nathan Cummings, 1954), 1. ↩︎

-

“Gaffron Collection Acquired,” 3. Cummings gave just over three hundred ancient Andean works to the Art Institute between 1956 and 1960; he donated much of the remainder to The Met. In 1963, Cummings agreed to an exchange between the two institutions to better balance out each’s holdings. ↩︎

-

Daniel Catton Rich, “Report of the Director,” Art Institute of Chicago Annual Report 1954–1955 (1955). ↩︎

-

Harry L. Shapiro, “Primitive Art and Anthropology,” Curator 1 (1958): 51. The popular interest in non-Western art at midcentury also influenced anthropological institutions. In 1957, the Chicago Natural History Museum established a new division of primitive art within the Department of Anthropology to highlight this area of his holdings and installed a new installation entitled What is Primitive Art? founded in “an anthropological approach to the study of primitive art.” Clifford C. Gregg, Report of the Director to the Board of Trustees for the Year 1957 (Chicago Natural History Museum, 1958), 42; Clifford C. Gregg, Report of the Director to the Board of Trustees for the Year 1958 (Chicago Natural History Museum, 1959), 26, 52. ↩︎

-

Minutes for a meeting of Committee on Primitive Art, April 29, 1957, Institutional Archives, Art Institute of Chicago. ↩︎

-

Alan R. Sawyer, “The Primitive Arts Department Features Oceanic Art,” The Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 52, no. 2 (1958): 36. ↩︎

-

Minutes, April 29, 1957. ↩︎

-

Minutes for a meeting of Committee on Primitive Art, May 24, 1961. Institutional Archives, Art Institute of Chicago. The department’s practice of exchanging and selling “surplus” ancient Andean works to museums, dealers, and private collectors in order to augment its other collecting areas largely ended in the early 1970s. ↩︎

-

Wardwell, Primitive Art from Chicago Collections, [i]. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Evan Maurer, “The Primitive Art Collection in New Quarters,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 72, no. 3 (1978): 15. ↩︎

-

Allen Wardwell, Primitive Art in the Collections of the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 1965), [i]. ↩︎

-

Maurer, “The Primitive Art Collection.” For an insightful review of Maurer’s impact, see Berzock, “Changing Place, Changing Face,” 159–60. ↩︎

-

As early as 1965, the museum determined it would not pursue Oceanic art—an area where the Chicago Natural History Museum of Chicago excelled; instead, it identified opportunities for growth in African and Mesoamerican art. See Wardwell, Primitive Art in the Collections, [i]. ↩︎

-

The first African art curator was Ramona Austin, hired in 1987; she was followed by Kathleen Bickford Berzock in 1995 and Constantine (Costa) Petridis in 2016. ↩︎

-

Richard F. Townsend, ed. The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes (Art Institute of Chicago, 1992), 112. ↩︎

-

Virginia Miller argued that the theme “sacred landscapes” was not expressed in the exhibition; however, it was more fully articulated in the catalog. “Exhibition Review: The Ancient Americas,” Art Journal 52, no. 3 (1993): 84, 87; Roberta Smith, “Review/Art: Before the New World Met the Old,” The New York Times, December 31, 1992, p. C11. ↩︎

-

The 2011 Arts of Africa reinstallation was led by Kathleen Bickford Berzock; in 2019, these galleries were reinstalled under the current curator of the collection, Costa Petridis. ↩︎

-

These features would be removed in a 2020 gallery update. ↩︎

-

Richard F. Townsend, quoted in Kyle MacMillan, “Bring out the Masterpieces,” ARTNews 110, no. 2 (2011): 46–47. ↩︎

-

Richard F. Townsend, with contributions by Elizabeth Pope, Indian Art of the Americas at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago, 2016). ↩︎

-

Elizabeth McGoey et al., “Multiple Modernisms in the Americas: Old Favorites and New Stories,” The Art Institute of Chicago, May 24, 2022, https://www.artic.edu/articles/993/multiple-modernisms-in-the-americas-old-favorites-and-new-stories. ↩︎