“Central American Antiq.”

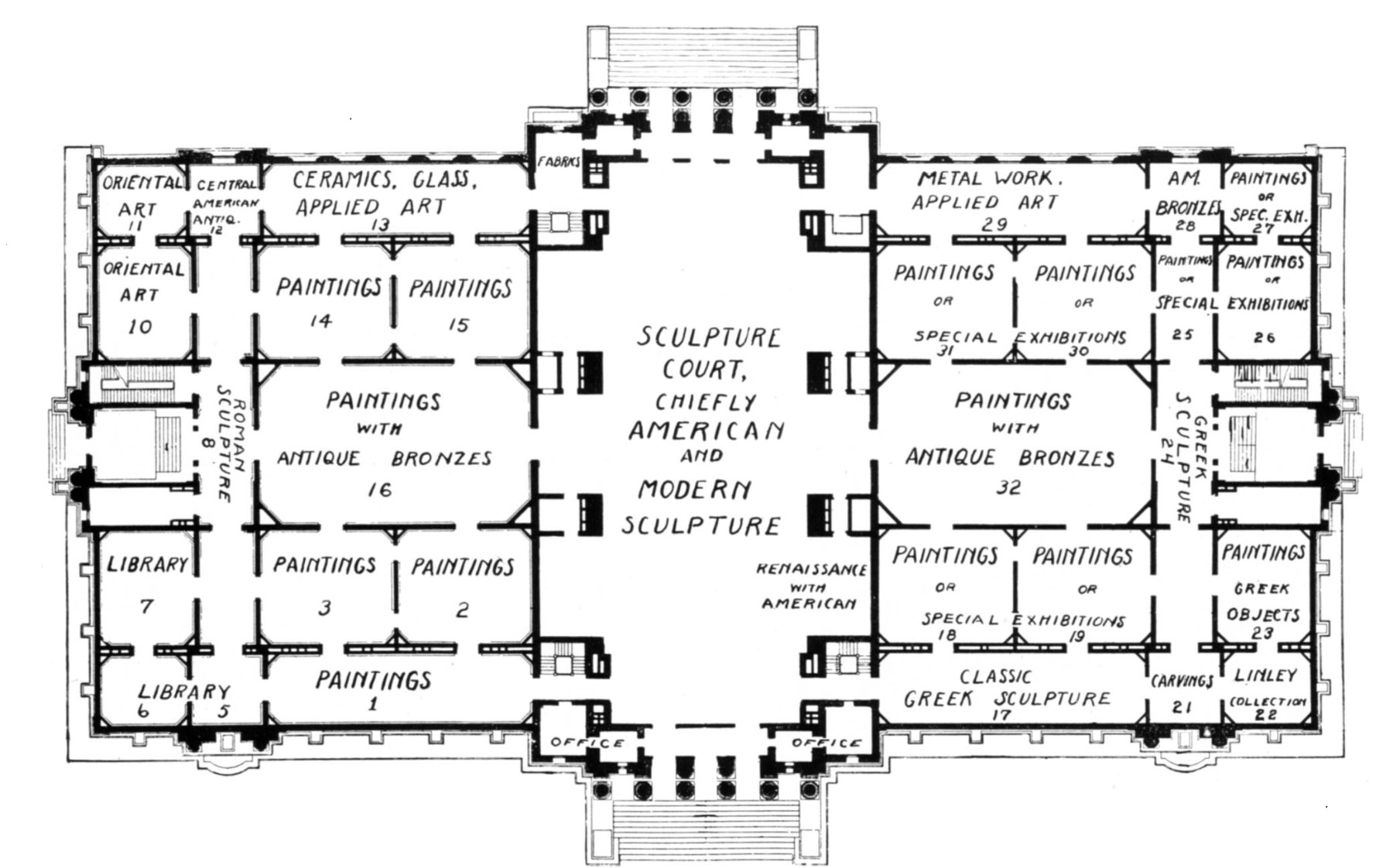

From its establishment within the Cass Gilbert–designed pavilion in Forest Park, originally made for the 1904 World’s Fair, the institution known today as the Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM) provided a space for the “other” Americas.1 Its architecture and spatial design defined and constrained the museum’s curatorial organization, with its Beaux-Arts galleries that privileged Western-style sculpture and painting.2 A 1914 plan demonstrates porous disciplinary, cultural, and chronological boundaries between and among archaeology and art history based on collection availability and institutional circumstances (fig. 1).3 Art historian Khristaan Villela’s research indicates that Gallery 12, dedicated to “Central American Antiq.” was in place by 1912.4 Most of the objects on view came from Edgar Lee Hewett’s excavations at the Maya site of Quirigua, partly underwritten by the Saint Louis chapter of the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA). As Villela has documented, though the AIA was unhappy with Hewett’s results, it nonetheless lent the objects to the museum. The chapter also assisted in organizing loans of Mississippian material from well-known collector Henry M. Whelpley, whose collection eventually went to the Saint Louis Academy of Science.5 With these small forays, Saint Louis belonged to the small club of municipal American art museums that displayed pre-Columbian art and archaeology (including, for a time, the archaeological heritage of the ancient Midwest) in the early twentieth century.6

From “Antique” to “Primitive”

By 1944, the museum had one gallery dedicated to the “primitive” arts, now located in the museum’s basement alongside the decorative arts period rooms, perhaps a subtle suggestion that these objects were décor for a modernist period room instead of art in their own right. Until the 1950s, the museum’s administrative and curatorial staff was quite small, and the directors of this period (always male) were assisted by a supporting cast of (usually female) curators and assistants. The museum did not have a dedicated curator for the primitive arts collection, but for thirty years, it had one curator reappointed on an annual basis, Thomas Hoopes, assisted by Catherine Filsinger. Hoopes had a background in arms and armor and became the kind of broad specialist one might expect. Filsinger seems to have provided the basis for future curatorial record keeping and correspondence. Hoopes and Filsinger, along with directors Perry T. Rathbone and Charles Nagel, fielded a few intriguing pre-Columbian acquisitions: a Teotihuacan mask (5:1948) in 1948 from little-known antiquities dealer Charles L. Morley, one of the blue-and-yellow feather textiles (285:1949) discovered in Corral Redondo, Peru, from Walram V. von Schoeler in 1949, and a pair of Mixteca-Puebla ceramics (85: 1950 and 86:1950) from the Stendahl Galleries in 1950. Additionally, they purchased a group of Paracas textiles from dealer John Wise in 1956.7 The AIA collections remained on loan until December 1961, when the chapter held a public sale in the museum’s Sculpture Hall.8 One of the few items that did not sell, a vase from Hewett’s excavations at Quirigua, remained on loan until 1990 when the chapter declined to donate it.9

The scattershot nature of these acquisitions underscores Saint Louis’s reluctance to develop an ancient American collection either because it lacked the resources or the sustained interest, or both. Rathbone described an environment where, perhaps as a result of the museum’s funding from a local property tax, the institution lacked robust financial support from the donor class, when compared to neighboring Kansas City, Chicago, and Cleveland.10 Eventually, a single collector with dedicated passions and deep pockets would drive the establishment of entire curatorial departments and become the largest single donor to the museum: Morton D. May.

Morton D. “Buster” May

Morton D. May, also known as “Buster,” collected art of all kinds so voraciously that his donations from the 1950s until his death in 1983 transformed the Saint Louis Art Museum into the encyclopedic institution it is today. Although he is most famous for his relationship with and avid support for the expatriate German painter Max Beckmann (1884–1950), he donated major works to almost every curatorial department in the museum.11 His donations created what is now the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas (AOA), constituting about 65 percent of the accessioned objects.

His fortune came from the family’s chain of department stores, which May steadily expanded in the 1950s and ’60s. He bought well-established local chains like Kauffman’s in Pittsburgh, D&F in Denver, Meier & Frank in Portland, and Hecht’s in Washington, DC, among others, steadily expanding the reach of May Company stores across the United States through the 1970s.12 While his business acumen is clear, his interest in art is less easy to explain. His archives, donated to the museum at his death and meticulously maintained and organized, do not include the kind of correspondence that describes great aesthetic passions, though May clearly had them. Instead, they are usually documents one might expect from a businessman accustomed to moving merchandise. His reflections, laconic though they are, indicate an awareness of the broader trend of collecting so-called primitive art alongside modernist design and architecture.13

Noting the presence of west Mexican sculpture in the home of the modernist architect (and May’s uncle by marriage) Samuel Marx, May decided he wanted some of his own.14 Marx designed May’s residence in Ladue, a wealthy Saint Louis suburb, though sadly the structure was torn down in 2005 (fig. 2).15 May’s acquisitions and loans in the 1950s focused on west Mexican material, readily available from West Coast dealers Edward Primus, David Stuart, and, of course, the Stendahl Galleries.16 African and Oceanic art came from Julius Carlebach, and it is in this mercantile relationship that we glean something of how May understood the intersection of collecting for himself and selling art commercially to a broader public. Carlebach’s Madison Avenue display “caught his fancy”—but not just for May’s own collection. He purchased some $20,000 worth of Carlebach’s Oceanic inventory—some placed on consignment at May Company stores and some sold privately.17 Similar exchanges for African art with Carlebach followed, alongside organized touring sales that visited multiple cities and involved multiple suppliers. It is tempting to connect May’s interest in Oceanic art with his service in the Pacific theater during World War II, but similar personal connections to his other art collecting areas is lacking. More likely he was participating in a broadly understood sense of the businessman as a humanist and philanthropist.18

Most of May’s objects were on anonymous loan to SLAM for many years. He gave small numbers of objects until the late 1970s when he began to make larger donations, including the final bequest in 1983. All gifts eventually carried his name. During his lifetime, May gave nearly 3,500 objects to the museum. Beyond the donations that established the AOA department, he also gave the museum nearly one hundred paintings and sculptures by German artists or artists living and working in Germany in the first half of the twentieth century. His donation of Beckmann paintings makes Saint Louis’s holdings the largest public collection in the world. From Russian religious garments to paintings and sculpture by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Jean Arp (1886–1966), the breadth of May’s donations places him among the great mid-twentieth-century collectors whose interests spanned the cultural production of Europe, the Americas, Africa, and the South Pacific.

In the 1990s, figures in the world of pre-Columbian art—Gillett Griffin, John Stokes, Julie Jones, David Joralemon—described May to me as someone who bought in quantity rather than quality and—in that most damning of connoisseurial judgment—someone who lacked “an eye.”19 While May bought some clunkers, in my experience going through the collection, as well as in conversations with colleagues at SLAM, it’s clear that May cultivated a different eye. He wanted to assemble a comprehensive collection of a given artist, or a given period, or a given region. He didn’t care if tastemakers thought late Beckmann wasn’t as good as early Beckmann. He wanted the full scope of an artist’s output over their career. In the case of May’s interests in Mesoamerica, that focus led to some purchases that seem prescient in retrospect, including a cache of small-scale obsidians, purchased from Valetta Malinowska in 1970, that is unlike almost anything known at the time but is very similar to material excavated from the Moon Pyramid almost fifty years later (fig. 3).20

Administering the Collection

As May’s loans and donations increased, so too did the museum’s curatorial staff, in an effort to accommodate the massive influx of objects and to steward the relationship between the donor and the institution. Emily Rauh succeeded Hoopes as a full-time curator in 1964.21 Her laser-like focus on contemporary art brought in major works. She later married Joe Pulitzer Jr., who like May, was a major donor of art and funds to the museum. Emily Pulitzer has since become a cultural philanthropist in her own right.22

In her time at SLAM, Rauh also hired and supervised curatorial staff in other areas, essentially creating one-person curatorial departments. She hired Philippa “Pippa” D. Shaplin, who had come to Saint Louis as a Washington University “faculty wife” and started working at the museum for a pittance despite her degrees from Smith College, Harvard University, and Wellesley College.23 Rauh promoted her to a full-time position in the wake of a bitter divorce that left Shaplin a single mother. In 1968, Shaplin left to become the registrar at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and, later, held a distinguished teaching career at Tufts University.24

Shaplin’s most significant responsibility during her tenure at SLAM was managing and documenting May’s numerous incoming purchases and loans. Complicating matters, May had a habit of buying objects from dealers, having them sent directly to the museum, and leaving them on loan without much of a commitment to donations or financial support.25 This could have led to chaos but for Shaplin’s assiduous organization and correspondence, still evident in SLAM’s curatorial files. She regularly communicated with experts at other institutions and added comments to object files. Aside from her own published work on Zapotec material, she has never been recognized for her role in shaping SLAM’s collection and doing the curatorial due diligence—politely cajoling the donor for more information, diplomatically coaxing dealers for confirmation, savvily gossiping with trusted colleagues and academics—that make the collection and its records such a valuable resource today.26 All of this likely helped solidify May’s loyalty to the institution. I was fortunate to exchange some letters with Shaplin before she passed away in 2011. She described herself as largely self-taught on the subject of pre-Columbian art, leaning on the 1957 text of that other autodidact Miguel Covarrubias.27 She developed an eye for what the collection needed and what might be available on the market, occasionally suggesting that dealers could usefully show plumbate ceramics to May, for example.28 Shaplin recalled May’s personal generosity with fondness, but perhaps because of the ephemeral nature of phone calls and day-to-day conversations, there’s little evidence that May consulted her opinion on acquisitions. Instead, the archive reflects his dependence on the expertise of specialists like Gordon Ekholm at the American Museum of Natural History. It was not unusual for May to go to a dealer, buy something, have it shipped to Saint Louis, send pictures to Ekholm, and finalize the purchase based on Ekholm’s evaluation and opinion.

A special pre-Columbian exhibition—drawn from “an extensive private collection” as well as the museum’s permanent collection—opened in the summer of 1965.29 Thereafter, the primitive art galleries, which opened in 1967, were split in two, with African art on the north side and pre-Columbian on the south of the museum’s lower level. The modernist presentation included cork squares as an accent material on the walls, perhaps meant to evoke blocks of tezontle (fig. 4). Ignacio Bernal, the director of Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Antropología (National Museum of Anthropology), came to give a lecture for the opening in February 1967, perhaps based on the existing relationship he had with May.30 May and Bernal had corresponded as the latter planned the new Museo Nacional, which Bernal hoped would encompass more than just the art of Mexico, as his request for Oceanic material from May’s collection suggests.31 May did sell Oceanic material for use in the new museum, even as the objects became part of the Museo de la Culturas instead. Mexican officials continued to approach May as a possible source for other archaeological and ethnographic objects. May suggested that they visit one of the many sales of African or ancient Mediterranean material then touring May Company stores. He also suggested that he would happily trade this material for “surplus items” of Mexican archaeological material.32 Though this never came to pass, it was not immediately dismissed. May was indeed recognized as one of the donors to the Museo de las Culturas del Mundo.33

Moving Merchandise

As May and Bernal’s correspondence suggests, archaeological and ethnographic objects had a much more fluid status in the 1960s than we might expect. For May, this is perhaps easiest to understand. He moved in a world of merchandise and shipments and thought nothing of selling objects as art and/or as decor in his stores. May (and the May Company) even gave objects away at the museum, as happened during an Association of Art Museum Directors meeting in Saint Louis in May 1964 and again in January 1968 at a College Art Association and Society of Architectural Historians meeting.34

As I have described elsewhere, May and James “Jimmy” Economos, the May Company’s fine arts curator (who had started out working for Carlebach), organized a pre-Columbian sale that opened at the Famous-Barr store in January 1966.35 It traveled over the next two years to several cities, including Los Angeles, Portland, Denver, Cleveland, and Washington, DC (fig. 5). The majority of the inventory for both the Clayton, Missouri, and Los Angeles sales came from the Stendahl Galleries to whom the May Company paid $95,000 for 2,350 objects (about $940,000 today).36 And when the sale-cum-exhibition opened, it included special letterpress invitations with RSVP cards for a lecture from one of the nation’s experts on pre-Columbian art, Alan Sawyer.37 Local press reported there were more than two thousand objects, with the most expensive being a $12,000 “clay Maya Figure with sun god headdress incised on a metal design.”38

An accompanying photo shows a Huastec sculpture (270:1978) that May had purchased in 1964 from the Carlebach Gallery (and that he donated to Saint Louis in 1978).39 May did record the inclusion of about fifteen pieces from his collection in the sale, and it seems he would have happily parted with this sculpture for $8,000.40 It may have helped encourage loss-leader shopping—if you won’t buy the $12,000 ceramic, perhaps we can interest you in a $5.00 ceramic stamp. Similarly extravagant pricing took place at the sale’s next stop, the glamorous May Company store in Los Angeles on Wilshire and Fairfax, designed by Samuel Marx (fig. 6).

There was ample advertising and reporting in the local press anticipating the LA show—perhaps because May Company staff knew that the sales numbers for the Famous-Barr presentation had been disappointing.41 The accounts mention the quantity of objects as well as the scholarly expertise of Economos, Sawyer, and H. B. Nicholson that went into vetting the material. Economos worked for the Carlebach Gallery before working with May. Sawyer, as mentioned, was a well-known specialist in Andean art from the Textile Museum in Washington, DC. Nicholson, a professor of Aztec art at the University of California, Los Angeles, lent authority to evaluations of the Mesoamerican objects. This gives a sense of how small and closely knit this network of academics, dealers, and collectors was (figs. 7 and 8). Out of some three thousand objects, prices ranged from $7.50 to $50,000.42 The more of something there was, the cheaper the price was. These valuations both paralleled and helped reinforce aesthetic hierarchies that continue to prompt scholars who evaluate objects: What makes a Maya object more valuable than a west Mexico object as a rule? Or a Teotihuacan vase a study piece rather than a masterpiece?

May told some of his correspondents that the LA sale was not successful, suggesting, in my opinion, that he did not recoup his costs.43 But the sale and others like it impacted museums across the US. Their collection databases include references to donations from the May Company in the years following, and it’s also possible that other donations from private individuals included objects purchased at the May sales without noting that provenance in their collection histories.44

Naranjo Stela 8, a large stone sculpture, brought drama and scale to the Wilshire sale. May purchased it from Everett Rassiga for $18,000 before directing his LA team to set its price at $50,000.45 Rassiga was one of May’s consistent suppliers, a significant dealer who consistently placed major and minor objects in private and public collections. Judging from letterheads, he, along with his wife Eugenia Álvarez, ran antiquities shops out of Dallas, Cuernavaca, and New York City. A decorated World War II pilot, who transitioned to commercial aviation after the war, he may have worked for American Airlines.46 This would explain his presence in Dallas and his affiliation with the Black Tulip gallery there in the late 1950s.47 By the mid-1960s, Rassiga had set up an eponymous gallery in New York. He lent nearly a third of the objects in The Jaguar’s Children, curated by Michael Coe for the Museum of Primitive Art.48 Rassiga’s most infamous role may be the looting of the Las Placeres facade, but that is not the only instance of his direct participation in large-scale, quasi-commercialized looting.49

In October 1966, Rassiga sold about one hundred objects to May, mostly ceramic, all Early Formative, and all traceable to one likely location: an area near San Pablo, Morelos, and adjacent to the local cemetery.50 Shortly thereafter, David Grove, then a graduate student at UCLA working under Nicholson, worked at San Pablo as part of his dissertation. Grove focused on the complex and then still poorly understood relationship between Olmec sites on the Gulf Coast and central Mexican sites like Las Bocas and Tlatilco that showed “Olmec influence.”51 Grove characterized his San Pablo excavations as salvage archaeology because of the evident looting and concluded that the cemetery mound had contained upwards of 250 burials.52 For Grove, tracing what had happened at the site involved a fair amount of ethnographic fieldwork in Mexico and the United States to understand the nature of local looting and international collecting.

As it happened, May and Nicholson were in regular contact. Following radiocarbon tests on a wooden Aztec sculpture, May wrote to Nicholson wondering if he would be interested in “carbon testing” bones May had as part of the purchase of “the entire contents of a Pre-Classic burial mound.” He enclosed twelve photos of some of the objects and the environs.53 One of the photographs shows a group of men clad in cowboy hats grouped around a pickup truck as a woman selects a vessel from a group lying on the ground (fig. 9). Others show single objects that eventually ended up in May’s collection, including one with a handwritten note: “There are several of this type and better too!” The handwriting is not May’s, nor does it seem to be Grove’s. I suspect that it is Rassiga’s and that the photos originally came from him.

Early in 1968, Grove wrote to Shaplin, referencing the material from San Pablo: “Most of the pot-hunting was instigated by the local San Pablo farmers, who sold to anyone interested. However, I think there may have been one instance of paid looting at the mound, and you may have received that material. I would estimate you may have 20% of the material from the mound.”54 Shaplin put two and two together later that year in a letter to Rauh: “I think Rassiga must have been fairly cooperative with the American archaeologisys [sic]. I believe they must have traced the illicit digging to him, and then he told them where the stuff was. . . . ‘I’ll tell you who has the stuff if you don’t tell the Mexiacn [sic] Museum that I was the digger’ etc.”55

Some of the objects May purchased from Rassiga appear in Grove’s 1970 article, without naming May (much less Rassiga).56 Grove estimated the looted objects from San Pablo to number around five hundred. It is an alarming reminder of the long-term damage done to the archaeological record and to our understanding of a still relatively contentious point in Mesoamerican studies. All of this information was an open secret to the dealer, the collector, his academic consultants, and even the staff of the museum that received the objects. For a variety of reasons, ranging from professional discretion to personal preference and institutional inertia, the knowledge lay scattered across multiple locations within multiple archives. Comparable stories could be told many times across all institutions that hold pre-Columbian objects.

End of an Era

Lee Parsons arrived at Saint Louis in 1974 after getting his doctorate at Harvard, conducting fieldwork at Izapa and Cotzumalhuapa, and working as the curator at the Milwaukee Public Museum.57 He began working on May’s collection leading up to a major reinstallation in 1980 and the publication of a collection catalog.58 Like other institutions, SLAM’s AOA department asked one curator to straddle three fields. Parsons’s first publication was on May’s Oceanic collection.59 In contrast to Shaplin, Parsons left behind very little correspondence at the museum. And May’s buying days were largely over, likely because of the growing pressure against pre-Columbian collecting in the early 1970s.60 Parsons left shortly after the pre-Columbian catalog was published in 1980.61 He became a freelance curator for hire, working on the Zollman collection and then the Kislak collection, before passing away in 1996.62

Parsons’s reinstallation includes some marvelously dated detailing like the space-age dome vitrines (fig. 10). A section of Colombian gold objects had a timed, motion sensitive light. There’s a greater use of context photos throughout the installation, and the division of two galleries was internally understood as “masterpieces” on one side and a “survey” on the other. The collection became static after May’s death in 1983. Without a significant patron applying pressure, the galleries completely installed, as well as the existence of a useful collection catalog, the museum moved its attention elsewhere, particularly to the African collection.63 Unfortunately, the saga of Mexican artist Brígido Lara and his forgeries of Veracruz ceramics that populate numerous American collections impacted how the museum and the community understood May’s collection.64 Three days of coverage in the local press took May’s reputation—and the museum’s—down a few pegs. The museum didn’t have a dedicated Americas specialist for the next twenty-six years.

I joined the museum in the summer of 2007 and worked toward a complete reinstallation of the ancient American collection that was completed in 2013. It included a more generous presentation of the Mesoamerican collection, small galleries for the Andes and the Isthmo-Colombian region, and the institution’s most notable Caribbean object, a Taíno duho collected in the nineteenth century.65 The new presentation incorporated North America and featured Southwestern pottery (some purchased in the 1940s from the notorious archaeologist Fain White King of Kentucky) and a selection of Mississippian material from local collections curated by Amy Clark.66

Conclusion

In 1916, Cass Gilbert proposed a plan to expand the Saint Louis Art Museum in the Beaux-Arts style.67 Such unrealized proposals can offer a glimpse of an alternate timeline—a history where Edgar Hewett didn’t have a falling out with funder Charles Bowditch, where the Saint Louis AIA chapter received magnificent objects from Palenque, which in turn created a nucleus of interest for pre-Columbian art such that director Perry Rathbone was able to persuade Saint Louis native Vincent Price to endow a curatorial chair for pre-Columbian art that Julie Jones later occupied, with David Grove as a colleague at the University of Missouri–Saint Louis. All of these alternatives are present in the archive. Their possibilities remind us that the collections we have are highly contingent entities, despite all our best attempts to smooth out their rough edges. We sort out the “fakes” from the “real” and curate cases of ceramics and jades, whose individual histories are fragmentary at best, in order to create representative selections of a distant past in an attempt to turn them into cohesive narratives for a museum-going public. But, in fact, the most cohesive narratives we have are the overlapping and intersecting stories that emerge from close examination of institutional and individual archives. If we are to understand these collections and the individuals who made them in all their complexity, we have to not only continue to collaborate but also find ways to ensure that these connections persist for future curators, museum staff, and members of the public so that they can make informed decisions about what happens to these objects next.

I thank former and current Saint Louis Art Museum staff members as well as many colleagues who offered their assessment of individual objects and the collection as a whole, including Amy Clark, Jason Gray, Jenna Stout, Norma Sindelar, Lynette Roth, Charlotte Eyerman, Ella Rothgangel, John Nunley, Brent Benjamin, Andrew Walker, Adam Sellen, Emily R. Pulitzer, Pippa Shaplin, Megan O’Neil, Mary Miller, Victoria Lyall, Rex Koontz, Joanne Pillsbury, John Pohl, Simon Martin, Virginia Fields, Sue Scott, Jeanette Bello, Janet Berlo, and Michael D. Coe. The opinions expressed in this paper are my own and do not represent the Library of Congress.

Notes

-

Founded in 1879 as the St. Louis School and Museum of Fine Arts, it was known as the City Art Museum after 1914 and formally changed its name to the Saint Louis Art Museum in 1971. See “Front Matter,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 1, no. 1 (1914): 15–19 ↩︎

-

Osmund Overby, “The Saint Louis Art Museum: An Architectural History,” Saint Louis Art Museum Bulletin 18, no. 3 (1987): 1–41. ↩︎

-

The fair had included a pavilion house sponsored by Mexico, but there is little evidence to suggest this had any long-term impact on the museum’s interest in what would come to be known as pre-Columbian art. Marshall Everett, The Book of the Fair: The Greatest Exposition the World Has Ever Seen (P. W. Ziegler, 1904): 273, 444; Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, Mexico at the World’s Fairs: Crafting a Modern Nation (University of California Press, 1996), 187–89. ↩︎

-

Khristaan D. Villela, “Viajes Pintorescos y arqueológicos: The Case of the Quiriguá Vase,” Pasatiempo, March 27, 2015, 32–35. ↩︎

-

Leonard W. Blake and James G. Houser, The Whelpley Collection of Indian Artifacts. Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis 32, no. 1 (1978). ↩︎

-

Richard F. Townsend, ed., Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South (Art Institute of Chicago, 2004). ↩︎

-

Catherine Filsinger, “Recent Pre-Columbian Acquisitions,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 35, no. 3 (1950): 39–43. In 1950, Rathbone attempted to persuade local hero and actor Vincent Price to endow an acquisition fund for pre-Columbian art. Price, sadly for future credit lines, demurred. Perry T. Rathbone to Vincent Price, October 25, 1950, Director’s Office General Correspondence (RG-001-001). Saint Louis Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

“Sale Announcement—Archaeological Institute of America,” December 3, 1961, File E3051, Registrar’s Office General Files (RG-003-002). Saint Louis Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

The chapter sold it at auction in 2014, where it was purchased by the Dallas Art Museum (Dallas Art Museum, 2014.42). See also, Margaret Gillerman, “St. Louis Archaeological Group Faces Revocation of Its Charter After Vote,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 15, 2015. Contrary to claims from the AIA–Saint Louis chapter at the time, the objects were not offered to the Saint Louis Art Museum, at least during my tenure at SLAM from 2007 to 2012. ↩︎

-

Oral history interview with Perry Townsend Rathbone, 1975 Aug. 8–1976 Sept. 24, 39–41, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↩︎

-

Lynette Roth, Max Beckmann at the Saint Louis Art Museum: The Paintings (Saint Louis Art Museum and Prestel, 2015); Lindsey Gruson, “Morton D. May Dies In St. Louis; Headed Department Store Chain,” The New York Times, April 14, 1983, p. B14. ↩︎

-

Edna Campos Gravenhorst, Famous Barr: St. Louis Shopping at Its Finest (History Press, 2014). See also Lyall, this volume. ↩︎

-

Sally Price, Primitive Art in Civilized Places (University of Chicago Press, 1989); Shelly Errington, The Death of Authentic Primitive Art and Other Tales of Progress (University of California Press, 1998). ↩︎

-

Lee A. Parsons, Pre-Columbian Art: The Morton D. May and the Saint Louis Art Museum Collections, Icon Edition (Harper & Row, 1980), ix. See also Liz O’Brien, Ultramodern: Samuel Marx: Architect, Designer, Art Collector (Pointed Leaf Press, 2007). ↩︎

-

Paul Hohmann, “The Ghost of Christmas Past: The Fall of the May Legacy in St. Louis,” Vanishing STL, December 19, 2008, https://vanishingstl.blogspot.com/2008/12/ghost-of-christmas-past-fall-of-may.html. ↩︎

-

Matthew H. Robb, “The Pre-Columbian as MacGuffin in Mid-Century Los Angeles,” in L. A. Collects L. A.: Latin America in Southern California Collections, ed. Jesse Lerner and Rubén Ortiz-Torres (Vincent Price Art Museum, 2017), 49–59; Michael D. Mathiowetz, “A ‘Cocktail and Buffet Supper’: The Social Networks of Archaeologists, Institutions, and Pre-Columbian Art Dealers and Collectors in Mid-Century Los Angeles,” April 26, 2024, paper presented at the symposium “Collecting Mesoamerican Art in the Twentieth Century: Revealing Histories of the International Art Market,” at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. ↩︎

-

“Playing the Art Market,” Business Week, January 11, 1964, pp. 28–29. ↩︎

-

David Brown, “Man of the Year: Morton D. May,” Globe-Democrat Sunday Magazine, December 27, 1959. ↩︎

-

Michael D. Coe, “From Huaquero to Connoisseur: The Early Market in Pre-Columbian Art,” in Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past, ed. Elizabeth Hill Boone (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1993), 271–90. ↩︎

-

See Helena Wayne, “Bronislaw Malinowski: The Influence of Various Women on His Life and Works,” American Ethnologist 12, no. 3 (1985): 529–40. ↩︎

-

“The Year in Review,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 48, no. 3/4 (1964): 20. ↩︎

-

“Advancing Art,” Harvard Magazine, January–February 2009, https://www.harvardmagazine.com/node/3849. ↩︎

-

“Back Matter,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 1, no. 1 (1965): 12. ↩︎

-

“Philippa Dunham Shaplin,” Burlington Free Press, February 24, 2011, https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/burlingtonfreepress/name/philippa-shaplin-obituary?id=10089295. ↩︎

-

Philippa D. Shaplin to Matthew H. Robb, November 26, 2011, AOA Department Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum. ↩︎

-

Frank H. Boos and Philippa D. Shaplin, “A Classic Zapotec Tile Frieze in St. Louis,” Archaeology 22, no. 1 (1969): 36–43; Philippa D. Shaplin, “Thermoluminescence and Style in the Authentication of Ceramic Sculpture from Oaxaca, Mexico,” Archaeometry 20, no. 1 (1978): 47–54; Adam Sellen, “Ancient Zapotec Material Culture and the Antiquities Market,” in The Market for Mesoamerica: Reflections on the Sale of Pre-Columbian Antiquities, ed. Cara G. Tremain and Donna Yates (University Press of Florida, 2019), 136–49. ↩︎

-

Philippa D. Shaplin to Matthew H. Robb, November 26, 2011. ↩︎

-

Philippa D. Shaplin to Alfred Stendahl, May 11, 1967, Box 1, Folder 13, Stendahl Art Galleries records, circa 1880–2003, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no. 2017.M.38. ↩︎

-

“Current Exhibitions,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 1, no. 2 (1965): 5. ↩︎

-

“Schedule Museum Events,” Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis 2, no. 5 (1967): 15. ↩︎

-

Megan E. O’Neil and Matthew H. Robb, “Building Museums, Building Collections: International Art Exchanges in Mid-Twentieth-Century Mexico City and Los Angeles,” May 11, 2017. Paper presented at the symposium “The Birth of the Museum in Latin America” at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. ↩︎

-

“Mexican Museums, 1963–1967; 1974,” n.d., Box 11, File 407, Morton D. May Papers (MSS-006). Saint Louis Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, El Museo de las culturas: 1865-1866, 1965-1966 (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1967). ↩︎

-

Sue Ann Wood, “Museum Directors Dig Into Grab Bag Valued at $50,000,” Globe-Democrat, May 28, 1964. ↩︎

-

Robb, “The Pre-Columbian as MacGuffin in Mid-Century Los Angeles.” ↩︎

-

Morton D. May, “[May Company Purchase],” August 17, 1965, Box 4, Folder 8, Stendahl Art Galleries records, circa 1880–2003, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no. 2017.M.38. ↩︎

-

Famous-Barr Photograph Collection, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis. ↩︎

-

George McCue, “2000 Art Items in Store Exhibit,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 6, 1966. ↩︎

-

Parsons, Pre-Columbian Art, 182. ↩︎

-

“Items Belonging to Morton D. May Entered into Pre-Columbian Show,” n.d., Box 11, File 396, Morton D. May Papers (MSS-006). Saint Louis Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Frank L. Kaplan, “Pre-Columbian Art Display Opens at May Co. Wilshire,” The News, May 19, 1966; “Crowd Views Pre-Columbian Art,” Van Nuys News and Valley Green Sheet, June 2, 1966. ↩︎

-

May Company, “Display Ad 32—‘Pre-Columbian Art,’” Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1966, sec. PART ONE, p. 32. ↩︎

-

Morton D. May, “Morton D. May to Alfred Stendahl,” June 20, 1966, Box 17, File 615, Morton D. May Papers (MSS-006). Saint Louis Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

See for example, National Museum of the American Indian, 24/3402 or Denver Art Museum, 1969.308. ↩︎

-

Matthew H. Robb, Daniel E. Aquino, and Juan Carlos Meléndez, “La Estela 8 de Naranjo, Petén: medio siglo en el exilio,” in XXIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, ed. Barbara Arroyo, Luis Alberto Méndez S., and Gloria Ajú Álvarez (Museo Nacional de Arquelogía y Etnología, Guatemala, 2016), 629–38. For a parallel case, see James A. Doyle, “The Odyssey of Piedras Negras Stela 5,” in The Market for Mesoamerica, 87–111. ↩︎

-

“War Decorations,” The New York Times, March 12, 1944. ↩︎

-

Christine Bertelson, “Art-World Buccaneer,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 15, 1987; Maureen Zarember, “Everett Rassiga, Art Dealer,” Tribal Art, no. 31 (Summer 2003): 95. ↩︎

-

Michael D. Coe, The Jaguar’s Children: Pre-Classic Central Mexico (Museum of Primitive Art, 1965). ↩︎

-

David A. Freidel, “Mystery of the Maya Facade,” Archaeology 53, no. 5 (2000): 24–28. ↩︎

-

“Notebook 5—Olmec-Aztec-Huastec-Tlatilco-Cuanhtitlan-Teotihuacan-Morelos-Mixtec,” 1966, Box 22, Notebook 5, Morton D. May Papers (MSS-006), Saint Louis Art Museum Archives; David C. Grove, “The San Pablo Pantheon Mound: A Middle Preclassic Site in Morelos, Mexico,” American Antiquity 35, no. 1 (1970): 62–73. ↩︎

-

David C. Grove, “The Morelos Preclassic and the Highland Olmec Problem” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1968). ↩︎

-

Grove, “The San Pablo Pantheon Mound,” 62. ↩︎

-

Henry B. Nicholson and Rainer Berger, Two Aztec Wood Idols: Iconographic and Chronologic Analysis, Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology, no. 5 (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, 1968); Morton D. May to Henry B. Nicholson, April 26, 1967, box 50, folder labeled “Pre-Classic,” Henry B. Nicholson papers (Collection 1863), UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles. The photos are in an unmarked envelope in box 16, folder 15. ↩︎

-

David Grove to Philippa Shaplin, January 2, 1968, Saint Louis Art Museum Archives. ↩︎

-

Philippa Shaplin to Emily Rauh, September 9, 1968, Object File 351:1978, Saint Louis Art Museum. ↩︎

-

Compare for example figure 5f in Grove, “The San Pablo Pantheon Mound” and figure 21 in Parsons, Pre-Columbian Art (SLAM, 1978). ↩︎

-

Lee A. Parsons, Pre-Columbian America: The Art and Archeology of South, Central and Middle America (Milwaukee Public Museum, 1974). ↩︎

-

Parsons, Pre-Columbian Art. ↩︎

-

Lee A. Parsons, Ritual Arts of the South Seas: The Morton D. May Collection ( Saint Louis Art Museum, 1975). ↩︎

-

Robert Reinhold, “Traffic in Looted Maya Art Is Diverse and Profitable,” The New York Times, March 27, 1973; Karl E. Meyer, The Plundered Past: The Story of the Illegal International Traffic in Works of Art (Hamish Hamilton, 1974). Copies of Reinhold’s New York Times articles were included in the object file for Naranjo Stela 8, along with May’s correspondence with his lawyer that negotiated the terms of the return of title of Naranjo Stela 8 with Juan Asensio Wunderlich, Guatemala’s ambassador to the United States. ↩︎

-

For more on Parsons, see Becky Cooper, We Keep the Dead Close (Grand Central Publishing, 2020). ↩︎

-

Lee A. Parsons, John B. Carlson, and Peter D. Joralemon, The Face of Ancient America: The Wally and Brenda Zollman Collection of Precolumbian Art (Indianapolis Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press, 1988). ↩︎

-

John Nunley, an African specialist, became the first Morton D. May curator in 1991. ↩︎

-

Martha Shirk, “Making History in Clay,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 28, 1987; Martha Shirk and Christine Bertelson, “Art Collectors’ Risks Grow,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 14, 1987; Martha Shirk, “Mexican’s Art Is Legal, Lucrative,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 15 1987; Martha Shirk and Christine Bertelson, “‘Endemic’ Problems,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 16, 1987. ↩︎

-

Parsons, Pre-Columbian Art, 217; Joanna Ostapkowicz et al., “Chronologies in Wood and Resin: AMS 14C Dating of Pre-Hispanic Caribbean Wood Sculpture,” Journal of Archaeological Science 39, no. 7 (2012): 2238–51. ↩︎

-

Matthew H. Robb and Amy C. Clark, “The Ancient American Installation at the Saint Louis Art Museum,” Tribal Art, no. 69 (Autumn 2013): 74–82. ↩︎

-

Cass Gilbert, Barbara S. Christen, and Steven Flanders, Cass Gilbert, Life and Work: Architect of the Public Domain (W. W. Norton & Co., 2001): 248. ↩︎