The Brooklyn Museum began actively collecting the ancient arts of the Americas in 1929 with the appointment of Herbert Joseph Spinden (1879–1967), who succeeded Stewart Culin (1858–1929) as the institution’s second Curator of Ethnology (fig. 1). The four case studies presented in this essay foreground Spinden’s central role in the acquisition of some of the institution’s most iconic works.1

Before coming to the Brooklyn Museum, Spinden was already well known for his pioneering work on ancient Maya art and held curatorial positions at the American Museum of Natural History, Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, and the Buffalo Museum of Science. Born in Huron, South Dakota, in 1879, Spinden studied anthropology and archaeology at Harvard University, culminating in a PhD in 1909.2 Upon his arrival at Brooklyn, he reinstalled Culin’s Rainbow House Gallery of Ethnology and commenced building the museum’s collection of prehispanic, Spanish American, and ethnographic objects from Mexico and Central and South America (fig. 2). Despite being an archaeologist, Spinden focused on the aesthetic qualities of Indigenous art and called for the desegregation of museum categories such as ethnology and fine and decorative arts.3 He rejected the word “primitive,” insisting that prehispanic traditions such as Andean weaving and Maya monumental architecture were superlative art forms.4 From 1931 until his retirement in 1950, he acquired almost eleven thousand works for the museum and went on at least seven collecting expeditions.5

New-York Historical Society

The first case study highlights one of the earliest collections of prehispanic works in the United States. Initially owned by the New-York Historical Society (now the New York Historical) in New York City, the collection was a product of donations from antiquities collectors during the first half of the nineteenth century and consisted of approximately 385 works from Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, and the United States.6

In 1936, the New-York Historical Society began an expansion of its Central Park West building. Philip Youtz (1895–1972), the director of the Brooklyn Museum, and Alexander J. Wall (1884–1944), the society’s librarian, were in frequent communication about the society’s need for temporary storage of its Egyptian, prehispanic, Native American, and Assyrian relief collections. Youtz, a trained architect, was appointed assistant director in 1933 and full director in 1934. During his brief tenure (through 1938), he initiated sweeping changes, such as removing the building’s deteriorating front stairs, creating an entrance hall, and reorganizing and reinstalling the galleries with a new focus on cultural history and the social and industrial implications of art.7 Youtz introduced to Wall the idea of a loan in May 1936, and Wall was receptive, acknowledging that there was no space in the new building’s plans for these collections.8

Youtz asked Spinden to examine the society’s prehispanic collection.9 Spinden may have been familiar with some works, especially if he saw the Huastec sculptures on display at the society’s previous location on Second Avenue and 11th Street (fig. 3).10 Given the breadth and quality of the collection, Spinden was likely enthusiastic. In January 1937, the agreement was finalized, and the collections, with their display cases, were transferred to the Brooklyn Museum and installed in the galleries (fig. 4).11 As part of the loan agreement, museum curators were required to submit biannual reports. In December 1938, Spinden wrote, “All of the large and important Mexican sculptures have been placed on exhibition, as well as the pottery from Campeche, Tampico, etc. collected by B. M. Norman; also a cylindrical Maya vase with painted design, a tripod bowl from the highlands of Guatemala . . . and several of the finer examples of Peruvian pottery.”12

Collector Benjamin Moore Norman (1809–1860) grew up in Hudson, New York, and took over his family’s bookstore after his father’s death. He eventually settled in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1837, where he opened a bookstore on Camp Street. Inspired by the success of John Lloyd Stephens’s 1841 book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán, Norman decided to travel to the Yucatan in 1842.13 During the four-month expedition, he visited archaeological sites and towns and later documented his travels in the book Rambles in Yucatan, published in 1843.14 Norman illustrated the travelog with his own drawings, including sketches of twenty Maya ceramic figurines and vessels collected during the trip (figs. 5 and 6).15

Norman acquired the Maya Jaina figurines from the Camacho brothers, Presbyterian priests who lived in the port town of Campeche.16 Leandro (1792–1849) and José María (1796–1854) Camacho were passionate collectors and established what may have been the first museum in the republic of Mexico to house their vast and eclectic collection.17 In Rambles in Yucatan, Norman describes visiting them and writes, “They were extremely kind; and presented me many interesting antiquities of their country.”18

Norman’s second expedition to Mexico occurred in 1844 and lasted a little over four months. He documented the trip in another travelog, titled Rambles by Land and Water, or Notes of Travel in Cuba and Mexico, which was published in 1845. After a few weeks in Cuba, Norman traveled to Mexico’s Gulf Coast, arriving in the port city of Veracruz. He then traveled north by boat up the Pánuco River to the town of Tampico in the state of Tamaulipas. There, he met Franklin Chase (1807–ca. 1893), the US Consul of Tampico, and his wife, Ann (1809–1874).19 The three became friends, with Ann Chase even nursing Norman back to health when he had malaria at the end of the expedition.20 Norman’s explorations around the Pánuco River were productive. There, he collected his first Huastec sculpture: a human face carved in relief on an irregular stone block from the site of Rancho de las Piedras (fig. 7). In addition, he collected two small ceramic vessels at Cerro Chacuaco, near the town Pánuco, and several ceramic figurine fragments in the countryside around the Tamesí River.21

Norman also procured three monumental Huastec stone sculptures: a Ritual Vessel (37.2896PA), a Standing Male Figure (37.2898PA), and the Apotheosis or Life-Death Figure—considered the most complex and exquisite Huastec sculpture outside of Mexico (fig. 8).22 It is likely that, while he was recovering from malaria in Tampico, Ann Chase coordinated the acquisition. Though the exact timeline is unclear, we know she was the source because of an undated document titled “The Idols” that, while unsigned, was likely authored by Norman. It reads: “Those interesting relics were discovered several years ago by an American, whilst exploring the Country of the Sierra Madre, near San Vicente, State of San Luis Potosi, Mexico. Much labor was required before they could be cleared away from the ruins under which they were buried. They were brought away from the mountains on wooden sleds to the river San Juan, from thence to the river Pánuco, in canoes, down to the town of Tampico, and were presented to B. M. Norman by Mrs. Ann Chase.”23 The effort of unearthing and transporting three sculptures weighing approximately one thousand pounds through jungle, down two rivers, and across the sea to New York was a monumental undertaking in 1844.

Surprisingly, the New-York Historical Society’s record of the 1844 donation only includes the items collected by Norman himself and not the sculptures gifted to him by Ann Chase.24 Spinden speculated that they may have been transported on a different ship and reached New York City too late to be included in the society’s proceedings, however, they are not recorded in any subsequent acquisition records.25

The Brooklyn Museum’s loan arrangement with the society went smoothly for twelve years until June 1949, when the society informed the museum that the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) had made an offer to purchase the three Huastec sculptures and a Maya vase.26 An alarmed Spinden warned of the proposal’s dire consequences, “Let me be frank in stating my considered opinion: if we fail to obtain these pieces we will never find their like again . . . [and] we will lose by far the finest original pieces in our Mexican collection.”27 The museum’s Governing Committee was swayed by Spinden’s pleas and approved the purchase of the Society’s entire prehispanic collection in 1950.28

Minor C. Keith Collection

Spinden’s commitment to building the ancient Americas collection is exemplified by the second case study involving a large collection of Costa Rican antiquities. In 1931, two years after her husband’s death, Cristina Castro Keith (1861–1944) contacted the Brooklyn Museum to donate over nine hundred prehispanic works in memory of her husband, Minor Cooper Keith (fig. 9). Spinden made an appointment to see the collection in her Babylon, Long Island, home. Immediately impressed, the following day he wrote to a moving company to arrange the packing and transport of the donation to the museum.29

Born in Brooklyn in 1848, Minor Keith made his fortune in Costa Rica during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, first by constructing a rail line from the Caribbean coast to the capital of San José and then as the country’s first producer and exporter of bananas on a commercial scale. He was cofounder of the United Fruit Company, which covered the Costa Rican countryside with plantations, later expanding into other Central American countries.30 Keith introduced bananas to the American diet, using the new railroad to transport them from inland plantations to the coast for export. His financial success was solidified when he married Cristina Castro Fernandez, the daughter of a former Costa Rican president, in 1883.31

Keith caught the archaeology bug when an uprooted tree on his Las Mercedes plantation exposed over thirty gold ornaments that had been deposited in a burial around 500 to 1,200 years ago.32 From that moment on, he employed a crew of excavators at Las Mercedes and other ancient sites disturbed by his many environmentally destructive, land-clearing projects.33 During more than twenty-five years in Costa Rica, Keith amassed a collection of over sixteen thousand objects, which he gradually brought to the United States and kept in his Long Island home.34 The carefully cataloged, but poorly documented, collection came primarily from Limón province on the Caribbean coast, particularly around the site of Mercedes and the Las Mercedes plantation, but Keith also purchased smaller collections from the central highlands, the southern area near the Panama border, and the northwestern region of the Nicoya peninsula.35 In 1882, he began making donations to US museums, and in 1914, he placed about seven thousand objects on long-term loan to the AMNH, where Spinden was an assistant curator. At the time, Spinden wrote that the collection was unrivaled in its beauty and richness.36

The 908 works donated to the Brooklyn Museum in 1931 included prehispanic pottery, carved stone sculptures, metates, and tools (fig. 10).37 More objects from Keith’s collection would soon follow. In 1934, the administrators of Keith’s estate decided to sell the entire collection that was on loan to AMNH. The enterprising American art dealer John Wise (1901–1981) bought the collection and negotiated with AMNH and Brooklyn to split it in half. Brooklyn Museum director Philip Youtz handled the negotiations with Wise. Contracts specified that George Vaillant of AMNH and Spinden, now at the Brooklyn Museum, would take turns selecting single objects until the whole collection was equally divided—about 3,500 items per institution (fig. 11).38

“The Paracas Textile”

The Brooklyn Museum’s iconic Nasca mantle, also known as “The Paracas Textile,” presents an interesting third case study because its itinerant history intersects with several prominent individuals and illustrates the influence of prehispanic art on modernism in the 1920s and ’30s (fig. 12).

The textile, renowned for the ninety needle-knitted figures around its border, was discovered sometime before 1924 by the huaquero, or grave robber, Juan Quintana at the Paracas cemetery of Cabeza Larga in southern Peru.39 Quintana sold the mantle to collector Domingo Canepa, a grocery store owner in Pisco.40 French scholar Jean Levillier (1893–?) examined the textile when Canepa’s archaeological collection was in Lima around 1924 and published the first detailed description in 1928.41 Elena Izcue (1889–1970), a Peruvian artist and future textile designer, illustrated the book’s frontispiece and produced two detailed watercolors of the border figures.42 In her publication, Levillier reported that the mantle was one of three textiles found in a mummy bundle of an old man whose head was adorned with gold ornaments.43 Canepa had brought his collection to Lima in the hope of selling it to the Museo de Arqueología Peruana, but the director, Julio Tello (1880–1947), decided against it, even though he acknowledged that the textile was “the gem of the collection.”44 Tello, instead, recommended that Rafael Larco Herrera (1872–1956), a Peruvian politician, businessman, and philanthropist, purchase it for his museum at Hacienda Chiclín near Trujillo, which he did sometime after 1926.45

In the 1910s, Izcue was teaching drawing in Lima’s schools and had begun incorporating ancient Nasca pottery motifs into her graphic designs for art-school textbooks (fig. 13).46 She and Larco Herrera met in 1921 and bonded over their shared interest in Peruvian archaeology and prehispanic art, which they viewed as central to the country’s national identity.47 Larco Herrera mentored the young artist and, in 1927, helped her win a two-year, government-sponsored fellowship in Europe. That year, Izcue and her sister, Victoria, moved to Paris to study interior design and graphic arts.48

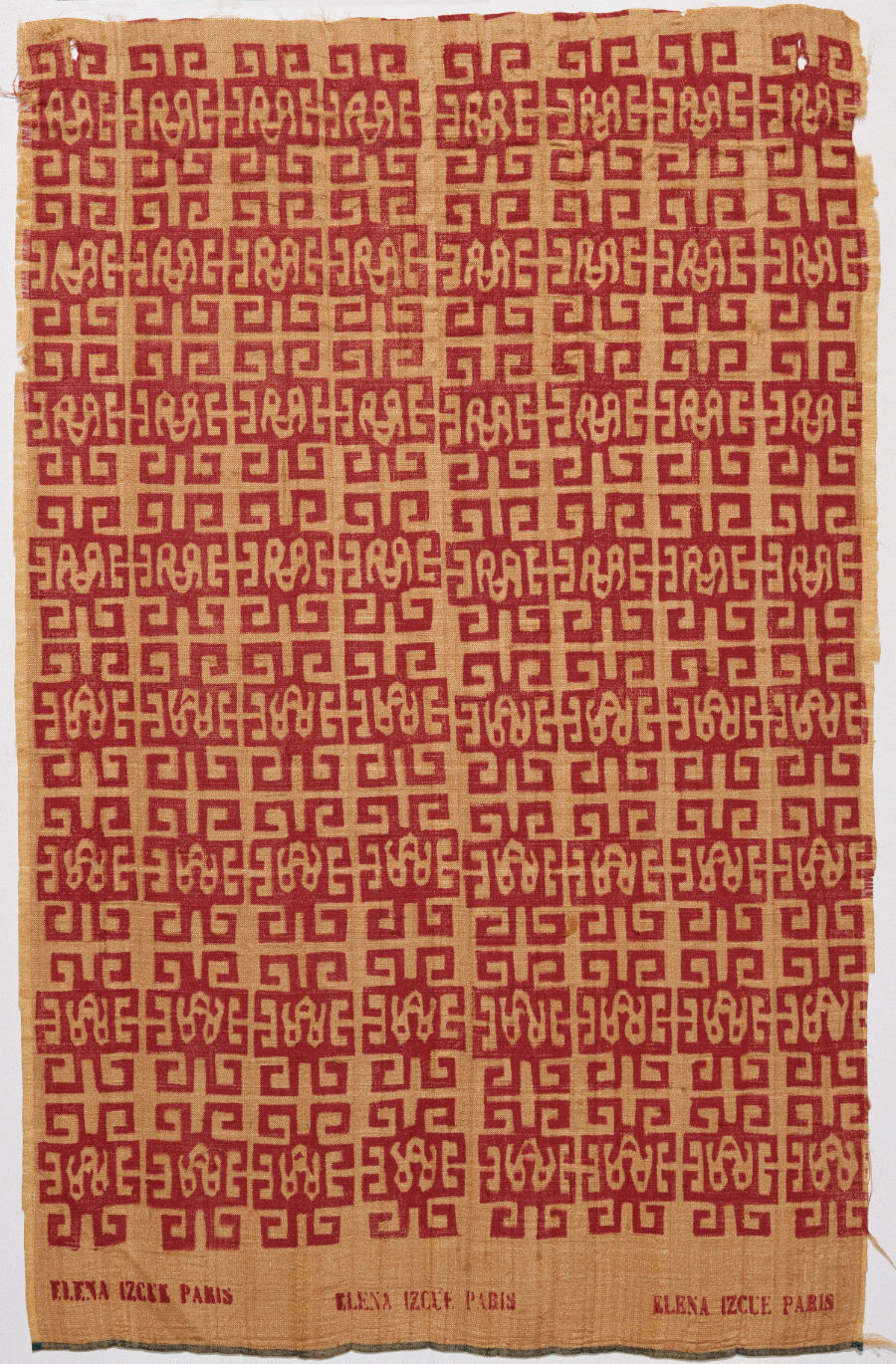

Remaining there for ten years, the Izcue sisters established a successful business of hand-printing contemporary fabrics with prehispanic motifs that were used for garments and accessories. Sometime after 1927, Larco Herrera sent the Nasca textile to Paris, where it was placed on loan to the Museum of Decorative Arts in the Marsan Pavilion of the Louvre. It was possibly at this time that Elena Izcue designed a fabric pattern reproducing the abstract faces of the mantle’s interior panel (fig. 14).49

During a 1935 visit to Paris, the American philanthropist Anne Morgan (1873–1952) became enamored with the Izcues’ fabrics and designs. She invited the sisters to show their work, in a special exhibition in New York’s Fuller Building on East 57th Street in December of that year. Planning began the month before, and it was decided to display the Izcues’ modern designs in conversation with ancient Andean textiles and pottery. Two exhibition committee members, M. D. C. Crawford (1883–1949), a textile scholar and editor of Women’s Wear Daily, and Philip Ainsworth Means (1892–1944), an anthropologist specializing in the ancient Andes, played prominent roles, selecting loans that included six Paracas and Nasca textiles from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.50 Crawford appealed to Youtz, writing, “My personal vanity is largely engaged in this project. I want the Brooklyn Museum, of which I regard myself as a part, to be adequately represented. . . . [I]n reading over the memorandum from Paris of the documents that are to be sent to this exhibition, I find that they are going to include, among others, the Paracas shawl which is, in my judgment, the greatest textile in the world. Therefore, I want the exhibits from the Brooklyn Museum to be [of] the highest distinction.”51 Crawford’s persuasion worked, and Spinden and Youtz approved the loan.

In 1935, Larco Herrera sent the Nasca mantle to New York for inclusion in the Izcue exhibition. The sisters transported it themselves from Paris, and Larco Herrera sent an additional twelve textiles from his museum.52 After the exhibition closed, Means convinced Larco Herrera to lend the mantle to the Brooklyn Museum.53 The spontaneity of the loan is indicated by a hastily handwritten note from Means to Spinden stating that he had the textile in his charge and was delivering it to the museum on December 19, the day after the exhibition closed.54 Spinden likely put it immediately on display in the recently renovated ancient Americas galleries.55

In 1937, Larco Herrera recalled the loan so the mantle could be exhibited in the Peruvian pavilion at the International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life, held in Paris’s Trocadero Museum from May to November of that year. Elena Izcue was commissioned to design the pavilion, and Larco Herrera shipped the textile to her in Paris.56 While the textile was on display, negotiations regarding its purchase began between Rafael Larco Hoyle (1901–1966), Larco Herrera’s son and director of the Larco Museum, and the Brooklyn Museum’s director. Larco Hoyle instructed Izcue to ship the textile back to Brooklyn at Youtz’s request, so it could be examined by the museum’s Governing Committee. Letters went back and forth negotiating the price. In one, Larco Hoyle expressed ambivalence about selling such a rare piece to an institution outside of Peru but conceded that he needed funds to support his museum and archaeological work.57 The textile returned to the Brooklyn Museum on December 23, 1937, and after months of fraught negotiations over the price, which almost scuttled the sale, the mantle was finally acquired on May 12, 1938.58

National Museum of Anthropology and History, Mexico City

The last case study takes us back to Mexico with the acquisition of forty-six prehispanic works in a 1948 exchange with the Museo Nacional de Antropología e Historia in Mexico City, hereafter referred to as the National Museum. The transaction took over ten years to accomplish and was the first of two collection exchanges between the institutions.59

The idea for an exchange was proposed in 1934 by Youtz, who desired monumental prehispanic sculptures to “give us an entrance hall that was unique” and would appeal to visitors.60 Spinden began discussions with officials at the National Museum in 1937 when he was in Mexico.61 After a pause during World War II, Spinden returned to Mexico in 1944 and resumed discussions with Eduardo Noguera (1896–1977), the director of the National Museum, and Ignacio Marquina (1888–1981), the director of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. The exchange was of interest to both directors because they wanted to expand into other collecting areas.62 Due to his knowledge of Mexican archaeology, the artist Miguel Covarrubias (1904–1957) served as an independent advisor on the project.

In June 1945, Brooklyn Museum Assistant Curator Nathalie Zimmern wrote to Covarrubias at the Barbizon-Plaza Hotel in New York City, enclosing a list of Brooklyn objects he had selected for the exchange.63 Covarrubias also assisted in the selection of archaeological material from the National Museum’s collection, provided values for all objects proposed by both institutions to ensure an equitable exchange, and served as a neutral, bilingual liaison between both parties.64

In 1946, the new director of the National Museum, Daniel Rubín de la Borbolla (1907–1990), and Brooklyn Museum’s new director, Charles Nagel (1899–1992), corresponded regarding conditions for the exchange. Rubín de la Borbolla included photographs of the proposed National Museum objects except for a group of Monte Albán funerary offerings that were recently excavated by Alfonso Caso (1896–1970) and were still being studied; these would be added later. He also wrote that the National Museum accepted the objects offered by the Brooklyn Museum but requested the addition of a Costa Rican stone stele and a gold ornament either from Costa Rica or Panama.65 Nagel responded that the museum’s Governing Committee approved the conditions but requested that the period for making changes be limited to six months. He added that he and the Governing Committee were completely satisfied with the objects proposed by the National Museum (fig. 15) and that if the Brooklyn Museum’s offerings were acceptable, “I see no reason why this mutually advantageous exchange cannot be put into effect.”66 With Nagel’s letter in hand, Spinden immediately wrote to Rubín de la Borbolla, emphasizing the rarity of the Costa Rican stone stele and wondering if the Brooklyn Museum might obtain a large exhibition-quality piece in exchange.67 The Aztec Year Bundle, which did not appear on the preliminary list, was likely added at this time (fig. 16).

Rubín de la Borbolla agreed to the six-month period, approving the exchange on March 4, 1947.68 The remaining correspondence relates to packing and shipping and final approval by Mexican President, Miguel Alemán Valdés. On December 24, 1947, Spinden received a Western Union telegram from Rubín de la Borbolla saying that the crates were on their way, and on March 10, 1948, they arrived at the museum.69 After the Governing Committee approved the acquisition, Nagel wrote to Covarrubias and Rubín de la Borbolla, expressing how pleased the committee was and thanking Covarrubias for his assistance.70

The project represented a significant early exchange between the National Museum and a foreign institution. In January 1948, Spinden celebrated with his Mexican partners at the Brooklyn Museum and the international exchange was announced in the spring 1948 Brooklyn Museum Bulletin (fig. 17).71 Spinden also organized a special exhibition What Cortés Saw in Mexico, which opened in September of that year and featured the new Aztec acquisitions (fig. 18). The completion of this transaction must have been truly gratifying for Spinden, who was winding down his long and productive career at the Brooklyn Museum.

The preceding case studies illustrate the diverse ways Spinden acquired prehispanic works during the ’30s and ’40s. From initiating purchases and courting donations to brokering exchanges with peer institutions, he took advantage of every opportunity to build the collection. His vanguard curatorial practice of presenting anthropological and archaeological collections as art put the Brooklyn Museum ahead of the curve compared to other fine art museums. Finally, Spinden was a man of his time who recognized the importance of the Pan-American relationships he developed during frequent trips to Latin America. His passionate advocacy of presenting prehispanic art in an encyclopedic art museum promoted the understanding and appreciation of the rich artistic traditions of the ancient Americas in New York and the United States more broadly.

The author would like to thank Kim Richter, Senior Research Specialist, Getty Research Center; Grace Billingslea, Curatorial Assistant, Arts of the Americas and Europe at the Brooklyn Museum; and Stephanie Crawford, Archivist, Brooklyn Museum Libraries and Archives.

Notes

-

The Mexico case studies are also included in the author’s forthcoming essay “Herbert Spinden and the Acquisition of Prehispanic Arts of Mexico” (working title) in Collecting Mesoamerican Art, vol. 2, ed. Andrew D. Turner and Megan O’Neil (Getty Research Institute). ↩︎

-

Robert L. Brunhouse, Pursuit of the Ancient Maya: Some Archaeologists of Yesterday (University of New Mexico Press, 1975), 94–95. ↩︎

-

For Spinden’s democratic approach to art, see Nancy B. Rosoff, “As Revealed by Art: Herbert Spinden and the Brooklyn Museum,” Museum Anthropology 28, no. 1 (2005): 47–56. ↩︎

-

This philosophy is ironically presented in Herbert J. Spinden, “Primitive Arts of the Old and New Worlds,” The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly 22, no. 4 (1935): 165. ↩︎

-

“Dr. Herbert J. Spinden. Conference and Field Trips, 1929–1950,” undated typescript, Folder: Herbert Spinden, Brooklyn Museum Employee Vertical File, Brooklyn Museum Libraries and Archives (BMLA). ↩︎

-

Inventory list of works lent by the New-York Historical Society, May 1937, Folder: Jarvis Collection (New-York Historical Society), 1938–1961, Series: Objects, Records of the Department of the Arts of Africa, the Pacific Islands and the Americas, RG-04.03, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Biography of Philip Newell Youtz (1895–1972), Philip Newell Youtz (PNY) records, Brooklyn Museum, accessed November 4, 2024, https://archives.brooklynmuseum.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/5; Philip N. Youtz, “Report of the Director,” Museums of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, Report for the Year 1934 (Brooklyn Museum, 1935), 5. ↩︎

-

Minutes of May 8, 1936, special meeting, Minutes of the Executive Committee of the New-York Historical Society, 1932–1936, 346, New-York Historical Society Digital Collections, accessed November 4, 2024, https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/nyhs%3A242695#page/346/mode/1up; Alexander J. Wall to Philip N. Youtz, September 11, 1936, Box 9, Folder: Museums: New-York Historical Society, 1936–37, Records of the Office of the Director Philip Youtz, RG-02.01, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Philip N. Youtz to Alexander J. Wall, September 14, 1936, Box 9, Folder: Museums: New-York Historical Society, 1936–37, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

The building on Second Avenue was the society’s seventh location from 1857 to 1908. R. W. G. Vail, Knickerbocker Birthday: A Sesqui-Centennial History of the New York Historical Society, 1804–1954 (New-York Historical Society 1954), 101. ↩︎

-

Draft agreement between New-York Historical Society and Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1937, Box 25, Folder 26, Records of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts & Sciences, RG-01, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Ibid.; Herbert Spinden to Alexander Wall, December 15, 1938, Folder: Jarvis Collection (New-York Historical Society), 12/1938–6/1961, Records of the Department of African, Oceanic & New World Art, RG-04.03, Series: Object Inquiries, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Raúl E. Casares G. Cantón, Yucatán en el tiempo: enciclopedia alfabética, Tomo IV (Inversiones Cares, S.A. de C.V., 1999), 363. ↩︎

-

B. M. Norman, Rambles in Yucatan, or Notes of Travel Through the Peninsula, Including a Visit to the Remarkable Ruins of Chi-Chen, Kabah, Zayi, and Uxmal (J. & H. G. Langley, 1843). ↩︎

-

Norman, Rambles in Yucatan, 248–61. The author has matched eleven works in Brooklyn’s collection with Norman’s drawings; however, NYHS has no record of his 1842 donation. ↩︎

-

Mary Miller believes that these figurines are among the earliest prehispanic works in the United States. Mary E. Miller, “Introduction: The Art of Ancient Mesoamerica, Collections Forged Before 1940,” in Collecting Mesoamerican Art Before 1940: A New World of Latin American Antiquities, vol. 1, ed. Andrew D. Turner and Megan E. O’Neil (Getty Research Institute, 2024), 14–15. ↩︎

-

Adam T. Sellen, “Los Padres Camacho y su Museo: Dos Puntos de Luz en el Campeche del Siglo XIX,” Península 5, no. 1 (2010): 53–54. ↩︎

-

Norman, Rambles in Yucatan, 267–68. Sellen’s research confirms that the Camacho brothers were the source of the figurines because Norman spent only three days in Campeche, which was not enough time to unearth the antiquities himself. Sellen, “Los Padres Camacho,” 60. ↩︎

-

The Chases had a successful mercantile business, which made them among the most influential and powerful residents in Tampico. Kim N. Richter, “Imperialist Ambitions, Black Gold, and Stone Figures: Collecting Huastec Sculptures before 1940,” in Collecting Mesoamerican Art before 1940, 264–65; B. M. Norman, Rambles by Land and Water, or Notes of Travel in Cuba and Mexico; Including a Canoe Voyage Up the Panuco, and Researches Among the Ruins of Tamaulipas, etc. (Paine & Burgess, 1845), 97, 108. ↩︎

-

Norman, Rambles by Land and Water, 197–98; Herbert J. Spinden, “Huaxtec Sculptures and the Cult of Apotheosis,” The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly 24, no. 4 (1937): 180. ↩︎

-

The Huastec relief panel (37.2895PA), two vessels (37.2777PA, 37.2779PA), and figurine fragments (37.2809PA, 37.2865PA) are illustrated in Norman, Rambles by Land and Water, 127–30, 150, 165, 169–70, 178. ↩︎

-

Spinden, “Huaxtec Sculptures,” 179; Kim Nicole Richter, “Identity Politics: Huastec Sculpture and the Postclassic International Style and Symbol Set” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2010), 1. ↩︎

-

The American referenced is unidentified. “The Idols,” no author, no date, General Correspondence, NYHS-RG2, Box 3, Folder 4, New-York Historical Society Archives. This document may have accompanied Norman’s donation letter. B. M. Norman to the New York Historical Society, November 1, 1844, General Correspondence, NYHS-RG2, Box 3, Folder 4, New-York Historical Society Archives. Spinden speculated that the actual site was Chilituju, located between San Vicente Tancuayalab and Tamuin. “Huaxtec Sculptures,” 180. Joaquin Meade identifies Chilituju as Cerro de Agua Nueva or Tzitzin-tujub or Xiil-tujub in Huastec. Joaquín Meade, Arqueologia de San Luis Potosí (Ediciones de la Sociedad Mexicana de Geografía y Estadística, 1948), 33, 35. ↩︎

-

New-York Historical Society, “Mr. Norman’s Donation,” in Proceedings of the New York Historical Society: For the Year 1844 (Press of the Historical Society, 1845), 46–47. ↩︎

-

Spinden, “Huaxtec Sculptures,” 180. ↩︎

-

R. W. G. Vail to Charles Nagel Jr., June 22, 1949, Folder: New-York Historical Society, 1948–1949, Records of the Office of the Director Charles Nagel, Series 1948–9, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Herbert J. Spinden, “Report on a Situation Affecting Ancient American Art,” September 27, 1949, Folder: Jarvis Collection (New-York Historical Society), 12/1938–6/1961, RG-04.03, Series: Object Inquiries, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Memo from Department of Primitive and New World Cultures to Mr. Nagel, January 15, 1950, Folder: Director [4] 01/1950 –12/1953, RG-04.03, Departmental Administration; William J. Conroy to Charles Nagel Jr., February 1, 1950, Box 25, Folder 26, RG-01; Charles Nagel Jr. to R. W. G. Vail, February 23, 1950, Folder: Objects Offered for Sale/Purchases by Museum, 1950, RG-04.03, Series: Objects 1949–1981, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Secretary of Dr. H. J. Spinden to Mrs. Minor Keith, December 7, 1931; Spinden to John H. Arink’s Sons, Inc., December 11, 1931, Series: Objects, Folder: Gifts: collectors [01] (05/1929 –12/1947), RG-04.03, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Watt Stewart, Keith and Costa Rica: A Biographical Study of Minor Cooper Keith (University of New Mexico Press, 1964), 1, 19. ↩︎

-

Alexander Benítez, “Minor Keith and the United Fruit Company,” in Revealing Ancestral Central America, ed. Rosemary A. Joyce (Smithsonian Institution, 2013), 73. ↩︎

-

Herbert J. Spinden, “Ancient Gold Art in the New World,” The American Museum Journal 15, no. 6 (1915): 307–8 ↩︎

-

Benitez, “Minor Keith and the United Fruit Company,” 72. ↩︎

-

Keith’s collection totaled 16,308 works: 15,527 specimens were recorded in the main catalog, and 881 were listed in a special catalog of gold and jade ornaments. J. Alden Mason, “Costa Rican Stonework: The Minor C. Keith Collection,” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 39, part 3 (1945): 201. ↩︎

-

Mason, “Costa Rica Stonework,” 199 ↩︎

-

Ibid.; Spinden, “Ancient Gold Art,” 307. ↩︎

-

Original Accession Record, Museums of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, December 1931, Brooklyn Museum’s Registrar’s Office; William Henry Fox to Mrs. Minor Keith, January 20,1932, Folder: Spinden, H. J. (Part 1), 1929–1933, Records of the Office of the Director William Henry Fox, 1913–1933, BMLA. ↩︎

-

George C. Vaillant to Philip N. Youtz, June 13, 1934; American Museum of Natural History Contract with John Wise, February 27, 1934; J. H. Morgan to Edward C. Blum, June 18,1934, Folder: John Wise 1934–1935, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Julio Tello and Toribio Mejía refer to the huaquero as José Quintana. Richard E. Daggett, “Paracas: Discovery and Controversy,” in Paracas Art and Architecture: Object and Context in South Coastal Peru, ed. Anne Paul (University of Iowa Press, 1991), 57n11. ↩︎

-

Ricardo D. Salvatore, Disciplinary Conquest: U.S. Scholars in South America, 1900–1945 (Duke University Press, 2016), 275n75. Julio Tello claims the textile was sold to Canepa in 1921. Julio César Tello, Paracas: Primera Parte. Publicación del Proyecto 8b del Programa 1941-42 de the Institute of Andean Research de Nueva York (Empresa Gráfica T. Scheuch S.A., 1959): Lamina LXXIX. ↩︎

-

Jean Levillier, Paracas: A Contribution to the Study of Pre-Incaic Textiles in Ancient Peru (Librería Hispano-Americana, 1928). ↩︎

-

Ibid., frontispiece, 9, and 33. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 18. ↩︎

-

Tello, quoted in ibid., 3n4. ↩︎

-

Daggett, “Paracas,” 39. ↩︎

-

Natalia Majluf and Luis Eduardo Wuffarden, Elena Izcue: Lima–Paris, années 30 (Musée du Quai Branly and Flammarion, 2008), 12. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 13. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 28. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 13, 32. ↩︎

-

Philip Ainsworth Means, “Elena and Victoria Izcue and Their Art,” Bulletin of the Pan American Union 70, no. 3 (1936): 253; “Peruvian Collection for Izcue Exhibition,” November 14, 1935, Folder: Peruvian Exhibition (Izcue Exhibition), 1935; Anne Morgan, “Report on the Izcue Exhibition,” 1935; Means, “The Archaeological Aspect of the Peruvian Exhibition,” 1935, 3–4, Folder: Peruvian Exhibition (Izcue Exhibition), 1935, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

M. D. C. Crawford to Philip N. Youtz, November 7, 1935, Folder: Peruvian Exhibition (Izcue Exhibition), 1935, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Philip A. Means, “The Archaeological Aspect of the Peruvian Exhibition,” Report on the Exhibition of Modern Peruvian Art by Elena and Victoria Izcue, no date, Folder: Peruvian Exhibition (Izcue Exhibition), 1935, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Philip N. Youtz to Philip A. Means, December 13, 1935, Folder: Peruvian Exhibition (Izcue Exhibition), 1935, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. The unplanned nature of the loan is indicated by the absence of an incoming receipt or internal memo in the Registrar’s Office; however, a 1935 loan number (35.286L) was assigned to the textile. Brooklyn Museum Registrar’s Office closed files for 38.121. ↩︎

-

Philip A. Means to H. J. Spinden, December 19, 1935, Folder: Peruvian Exhibition (Izcue Exhibition), 1935, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

“Annual Report of the Department of Primitive and Prehistoric Art, 1934”; “Annual Report of the Department of Primitive and Prehistoric Art, 1935,” Folder: Departmental Reports, 1929–1942, RG-04.03, Series: Departmental Administration, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Rafael Larco H. to Miss Anne Morgan, April 9, 1937; Rafael Larco H. to Philip N. Youtz, April 11, 1937, Folder: Objects Offered for Sale: Miscellaneous, 1937–1938, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA; Laurance P. Roberts to Edgar Weber, January 25, 1938, Brooklyn Museum Registrar’s Office closed files for 38.121; Rebeca Vaisman, “Iconos del diseño latinoamericano del siglo XX: Al encuentro de Elena Izcue,” Architectural Digest México y Latinoamérica, May 31, 2022, https://www.admagazine.com/articulos/elena-izcue-icono-del-diseno-latinoamericano-del-siglo-xx. ↩︎

-

Raphael Larco Hoyle to Philip Youtz, September 7, 1937; Philip N. Youtz to Raphael Larco Hoyle, September 17, 1937; Rafael Larco Hoyle to Philip N. Youtz, October 11, 1937, Folder: Objects Offered for Sale: Miscellaneous, 1937–1938, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Laurance P. Roberts to Herbert Spinden, May 12, 1938, Folder: Objects Offered for Sale: Miscellaneous, 1937–1938, RG-02.01, Youtz Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

The second exchange occurred in 1959. The Annual Report of The Brooklyn Museums, January 1, 1947–June 30, 1948 (Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1948), 39. ↩︎

-

Philip N. Youtz to Herbert Spinden, July 20, 1934, Folder: Director 1930–1938, RG-04.03, Series Departmental Administration, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Letter from Herbert Spinden to Antonio Mediz Bolio, March 29, 1937, Folder: Exchanges with National Museum of Mexico, 06/1959–04/1964, RG-04.03, Series: Objects, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Herbert Spinden to Isabel Roberts, October 22, 1944, Box 1, Folder: Depts: American Indian Art, 1944–1945, Records of the Office of the Director Isabel Spaulding Roberts, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Nathalie Zimmern to Miguel Covarrubias, June 28, 1945, Folder: Exchanges with the National Museum of Mexico [2], 03/1937–03/1948, RG-04.03, Series: Objects, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Hebert Spinden to Charles Nagel Jr., October 8, 1946, Box 1, Folder: Depts: American Indian Art, Records of the Office of the Director Charles Nagel Jr., RG-02.01, Series: 1946–47, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Daniel F. Rubín de la Borbolla to Charles Nagel Jr., December 23, 1946, Folder: Exchanges with the National Museum of Mexico [2], 03/1937–03/1948, RG-04.03, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Charles Nagel Jr. to Daniel F. Rubín de la Borbolla, January 23, 1947, Box 1, Folder: Depts: American Indian Art, RG-02.01, Nagel Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Herbert Spinden to Daniel F. Rubín de la Borbolla, January 24, 1947, Folder: Exchanges with the National Museum of Mexico [2], 03/1937–03/1948, RG-04.03, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Daniel F. Rubín de la Borbolla to Charles Nagel Jr., February 10, 1947, Box 1, Folder: Depts: American Indian Art, RG-02.01, Nagel Series; Daniel F. Rubín de la Borbolla to Herbert Spinden, March 4, 1947, Folder: Exchanges with the National Museum of Mexico [2], 03/1937–03/1948, RG-04.03, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Western Union Telegram from Daniel Rubín de la Borbolla to Herbert Spinden, December 24, 1947; memo from Department of Primitive Culture, March 10, 1948, Folder: Exchanges with the National Museum of Mexico [2], 03/1937–03/1948, RG-04.03, BMLA. ↩︎

-

Charles Nagel Jr. to Miguel Covarrubias, March 23, 1948; Charles Nagel Jr. to Daniel F. Rubín de la Borbolla, March 23, 1948, Box 1, Folder: Depts: Primitive & New World Culture, RG-02.01, Nagel Series, BMLA. ↩︎

-

The Brooklyn Museum Bulletin 9, no. 3 (1948): 18–19. ↩︎